Book & Backpack

Phillipa Davies (2001 ) looked at the homework debate and asked, “When is homework just too much?”

Davies quoted Harris Cooper, professor of psychology at the University of Missouri-Columbia, with regard to both recent and historical research on this topic.

According to Cooper, there is no relation between time spent on homework and achievement in the upper-level elementary school grades. Later in the article he pointed to the backlash from parents who feel “resentful” about the amount of time that has to be spent helping children with homework.

Mrs. S’s comments were made a decade ago, before the Tories introduced their new elementary curriculum. To achieve their objectives, the government ensured that learning expectations from intermediate grades would be downloaded to the junior grades, and junior expectations to the primary division. Of course, little or no resources, professional development or support were given to the classroom teacher.

With so many expectations in each division, many of which are developmentally inappropriate for young children, teachers have in turn passed some of the responsibility for meeting all these grade-specific expectations on to families in the form of homework. Teachers are telling families there are not enough hours in the school day to address all these expectations. Suddenly, families are crying that there is too much homework and have begun to question its validity. The pendulum has swung!

Many mothers and fathers, recalling their own childhood experiences, are witnessing the homework they did when they went to school in their child’s nightly assignments. Many concerned parents view drill assignments and research projects as necessary to build discipline and reinforce the skills and concepts taught between 9 a.m. and 3:30 p.m.

Some demoralized or inexperienced teachers are providing families with hours of this type of busywork. However, many elementary educators, particularly primary teachers, don’t favour traditional homework assignments. Instead, these teachers encourage activities such as reading, visiting museums and libraries, playing board games, solving word puzzles, walking, talking and storytelling.

But can such family-oriented activities be considered real work? Where are the 30 plus math questions? What about spelling lists and word exercises? Why aren’t the ditto sheets coming home?

As a result of conflicting views on what homework should be, many teachers find themselves debating with family members about the function of homework. Newly amalgamated boards of education have differing or no homework policies in place.

Mrs. S. was not an exceptional parent with strong opinions. Like many others, she was often sidetracked by ill-informed “back-to-basics” ideas she picked up from the media. Mrs. S. was an advocate for her son’s education but didn’t understand how teachers approach reading, writing, spelling, math and learning. She wanted to help, but there was a contradiction between the way she wanted her child taught and the way in which she perceived her child was being taught. The question remained: “How can families and teachers see themselves as partners in education, when views about the value of homework and learning differ?”

With each swing of the pendulum, education undergoes dramatic shifts. School looks and sounds very different from when Mrs. S. and I were students. The introduction of computers, the internet, reading recovery, the new curriculum, provincial report cards and testing have kept teachers busy. Many continue to take courses and look for opportunities to grow professionally so as to balance politically based changes with sound pedagogical practices. Time and communication are essential if families are to become attuned to the latest teaching practices and initiatives.

Implementing Book and Backpack

To address the concerns of Mrs. S. and to communicate with parents, I implemented a home-school program. Originally called Book & Briefcase, it soon became known as the Book & Backpack (or B & B for short) program.

In Real Books for Reading, Hart-Hewins and Wells (1990) promote the notion of an out-of-school reading program in which children share books with their families. In this program, which the authors called “Borrow a Book,” children take books from school home in a special bag that contains a comment booklet. For Hart-Hewins and Wells, the program has particular significance since “... children see their parents and their teacher together on something they both feel is important.”

Other teachers have also written about successful home/school programs. Their thoughts gave me the idea for Book & Backpack. In The Writing Suitcase by Rich (1985) and The Writing Box by Maloy and Edwards (1990), the idea was to fill a suitcase with writing materials to encourage language development at home.

I liked the idea of having the children become actively engaged in the process of writing at home and decided to include a book to be read for homework in the backpack. Thus the evolution of Book & Backpack began.

Early in the school year, I purchased three durable backpacks. The idea of carrying materials in a “special” backpack that went home for the night was very appealing to children. Every year, the children gave the backpacks special names. In each backpack were items such as paper, pencils, markers and crayons. Along with writing and drawing materials, each child took home a book or magazine from the classroom library.

The class was organized into nine groups with three children in each group. Everyone was assigned to a specific backpack, and the backpack was rotated through the group. Every child took the backpack home once every two weeks. To ensure that each child knew when it was his or her turn, students asked their families which evening they preferred. A list of the nine groups, children’s individual names and a schedule was posted on the wall.

For example, a student in group four would know that if someone in group three had B & B on Friday, he or she would be taking the backpack home the following Monday. If the regular schedule wasn't convenient for a child, he or she could trade their day with someone else in their group.

When B & B was launched, the children and I discussed the implications for fellow classmates when a backpack wasn’t returned. We looked at alternative solutions to ensure that the backpack was returned when someone was sick. Forgotten backpacks were seldom a problem.

The expectation of B & B was for each child to share his or her book with a family member (preferably an adult). Also, children were asked to respond to the book in some way — through discourse, writing, drawing or making. Some children wrote letters to their classmates about the story; some wrote stories patterned on the book they read (perhaps with the help of an older sibling); some drew their favourite part of the story; some made constructions; and a few even made tape recordings based on the book talk they had with family members. The expectation was that each of the three children assigned a backpack would have something prepared and ready to share with their classmates the next day.

Alongside the reading and writing materials in the backpack was a duo tang folder, which became known as the “Parent’s Journal” or the “Adult’s Homework.” Every two weeks, a professional article and blank paper was included in the backpack, asking family members to respond to the article, raise questions, or make comments about what had transpired at home.

The Children Learn

Every year since the beginning, B & B has exceeded my expectations. First and foremost, B & B promoted a sense of ownership and commitment for the children. It was everyone’s responsibility to make sure that the backpack was sufficiently supplied with writing and drawing materials. Children knew they were expected to transport the case safely and return the backpack to school the next day. The children relied on each other to meet these expectations.

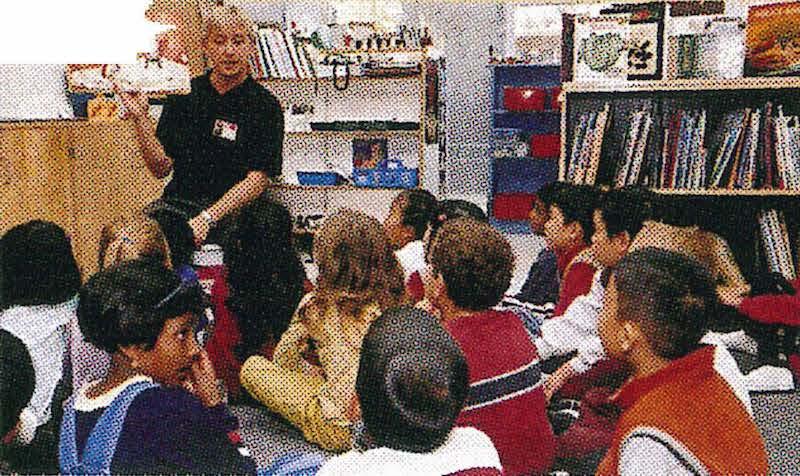

Because the children knew they would be sharing their ideas and creative work with one another, they became motivated by the expectations created by B & B. Time was set aside each day for the children to talk about their involvement with the program. This sharing time was very crucial to the program’s success. Children would talk enthusiastically about their book, their responses and creative work. This show-and-tell concept promoted language opportunities as children described, explained, questioned, demonstrated and reported their involvement with B & B. As the audience, the children praised each other’s efforts and exchanged positive comments, questions and suggestions. Motivated by what their peers had shared, children would often hitchhike on each other’s ideas, perhaps writing a longer story or working on an art activity just like their friends.

Another consequence of B & B was that, during class time, many children chose to continue with the reading or response activities they had started at home. Several stories that began as homework were developed and eventually published. When a child enjoyed a particular book, he or she might spend time re-reading the book, reading it aloud to a friend or perhaps investigating other titles by the same author.

B & B offered the children a sense of empowerment, prompting them to make choices: the choice of which books to read, the extensions to share and discuss in class. The work that emerged from B & B provided data for assessment purposes. Writings and drawings were stored in each child’s personal file or portfolio; books were recorded in reading logs; and samples of the student’s work were referred to when it came time to write report cards or communicate with families. B & B provided a strong focus for assessment and discussion.

Many families were thrilled to see their child so motivated.

They also saw the activities their children were involved with as meaningful.

Parents Learn Too

Not only did B & B stimulate the children’s learning, it was also a vehicle for educating families. For one thing, the enclosed articles provided information on current educational theory and practice. Secondly, adults were encouraged to write questions and concerns in the journal, and a network was developed between parent and teacher and between adults of different families. Frequendy, parents would raise questions about curriculum or language learning and would invite a response from the teacher or another parent in the Journal. Sometimes, the adults would react to articles they had read in the newspaper or to programs they had seen on television, and they used the Journal to offer an opinion on what they thought should be happening:

“Thank you very much for giving me a chance to make a comment. In my opinion, spelling and pronunciation is also very important. In class students should be asked for correct spelling and pronunciation. Every day students could be assigned a specific topic and given spelling and pronunciation as homework. I am looking forward to meeting with you.” Mr. M.

After reading a comment such as Mr. M’s in the Journal, I often discuss the comment with the class so they can understand my intentions and why we do what we do. I would also follow up on Mr. M’s comment with a written response in the Journal; an article for him to read; or an excerpt from a curriculum document to give him information about what goes on in our classroom. Because Mr. M. went to school outside of Canada, his experiences with education are very different. Other adults might read my comments to Mr. M. in the journal and share their own views or experiences, thus further building a dialogue about spelling and language learning.

Finally, because I had to respond to the individual parent’s concerns, my own understanding of program was enriched. I was challenged to research, justify and articulate why I teach the way I do and my beliefs about how children learn.

The idea of B & B became so successful that we began to extend the program to include math, with a collection of materials that included tangrams, pattern block, calculators and backpack, poetry and backpack, jokes and backpack etc. For science and backpack, the children had the choice of several hands-on experiments that they conducted at home with their family. Observations on such experiments were recorded and presented to the class during sharing time. Reference books and science magazines were displayed in our classroom and became part of the backpack program.

Jane Baskwill (1989) provides insight into the relationship between families and teachers. “What we need is a shift in thinking about the nature of home/school communication, a new model of reciprocal responsibility based on a mutual understanding of what learning is. I dream of teachers communicating with parents on a regular basis, sharing everything they noticed about the child’s growth in learning. Indeed, even more important, I imagine parents doing the same with teachers, feeling it was their place and their right to do so.”

Is B & B Homework?

Many families were very satisfied that this program was a meaningful liaison between “school” work and “home” work. From the involvement of the children, the feedback of the parents and the enthusiasm in the classroom, B & B seemed to be homework that worked.

I thank Mrs. S. for her concerns eight years ago, and feel that B & B was one way to meet her demands for more homework. Moreover, through meaningful activities, B & B strengthened several partnerships: between child and teacher, child and child and teacher, child and parent, and parent and teacher. As educators, we must continue to foster these partnerships and hold them in high regard in order to enrich the learning of our students, regardless of what happens outside the classroom walls.

Jim Giles teaches grade 1 at Queen Victoria Public School, Toronto. Currently on a one-year teacher exchange to Australia, arranged by the Canadian Education Exchange Foundation (www.ceef.ca), he can be reached at jgiles100@hotmail.com.

References

Baskwill, Jane. Parents and Teachers: Partners in Learning. Toronto. Scholastic 1989.

Davies, Phillipa. "The Homework Debate - When Is It Just Too Much?" In Professionally Speaking. Toronto. Ontario College of Teachers. June 2001.

Hart-Hewins, Linda and Jan Wells. Real Books for Reading: Learning to Read with Children's Literature. Toronto. Pembroke Publishers, 1990.

Maloy, R.W. and S.A. Edwards. "The Writing Box: Kindergarten and First Grade Children's Writing at Home." Contemporary Education,

Vol. 62, No. 4 - Summer 1990. Rich, Susan J., "The Writing Suitcase." Young Children, July 1985.