Imagining a Future: Richness of Spirit

Terms such as “poor people” or, more sensitively, “people living in poverty,” evoke a range of images from homelessness to children coming to school without breakfast. Issues of poverty are usually defined in terms of material needs being met. Adequate food, water, clothing, shelter, are the baseline that we all hope to sustain. Health care, education, safe and equitable working conditions are unknown to many people in the world. These are essential goals, goals that ETFO members have made great progress toward.

Yet, having travelled to other parts of the world where the standard of living for many is considered abysmal, I have returned each time reflecting on how the quality of life in these “deprived” areas has seemed so rich, indeed has enriched my life. In Guyana, Guinea, Senegal, and rural India and China, I experienced an openness, a willingness to share, a vibrancy that would spontaneously manifest in song or dance, laughter or tears, prayer or reflective silence. People often held hands or linked arms when walking; personal space shrank but family and community space expanded.

How to reconcile such experiences with the well-documented negative impact that poverty has on student achievement? This question propels us to construct an understanding of what a “non-deficit” model means when we work in urban and rural schools whose communities are ravaged by poverty.

A recent study of health services in New York City noted an anomaly in the research about the recovery rates of hospitalized patients in correlation to their socioeconomic status. Recovery rates among Hispanic patients were far better than those of other groups. The conclusion of the study was that in contrast to well-off, usually white patients, who spent most of their time alone in a hospital bed, when one entered the room of Hispanic patients, one could often not find them, so enfolded were they by immediate and extended family. The research suggested that being part of a loving community has an impact on recovery rate by boosting a patient’s resiliency.

In the “One in Six” DVD that has been distributed by ETFO to every school in Ontario, playwright David Craig recounts a pivotal moment when an adolescent living in a family shelter is astonished to hear David suggest that he is poor. The boy considers homeless people to be poor, not himself. The DVD also spotlights the challenges for immigrants with foreign credentials and work experience: they bring so much and find so many doors closed to them.

Such examples caution us to not make assumptions about the lived experience of others. When living in poverty, families cannot include hopelessness as an option. Hope is pinned on resources that are accessible such as family, community, prior experiences. These are riches that are easily shared, even with outsiders. These are riches that flow into schools that are open to families and community members. They are the basis of a non-deficit model.

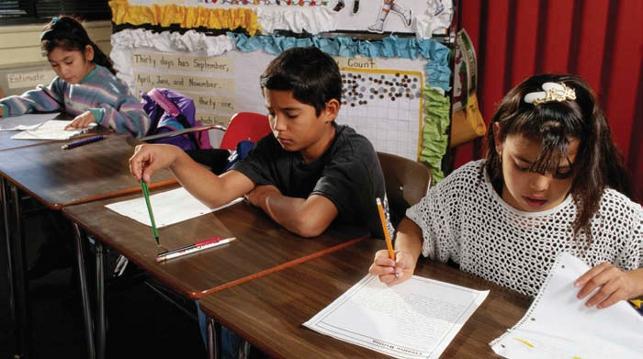

Many of our students come from deep faith traditions that they camouflage when they enter school. Many come from warm, vibrant extended families whose members’ names never appear on our registration documents, even though they may sleep in the same room. Many students have people who love them and sing songs to them in languages with generational resonances. Some are also Aboriginal, whose elders’ wisdom infuses their journey. They come into our classrooms, all these precious ones, rich in spirit. Let us not forget this when we talk of poverty.