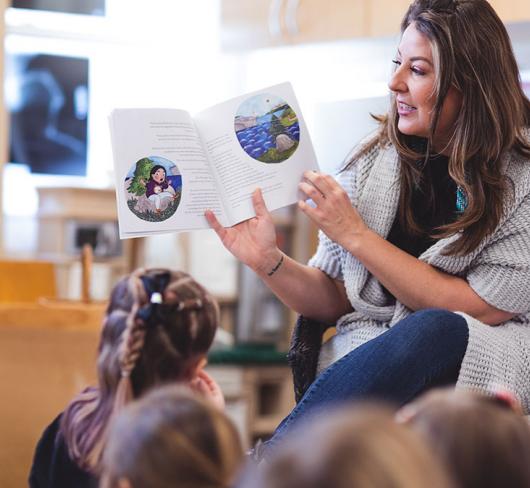

On the Blanket of Mother Earth: First Nations Environmental Education

Two times a week grades 3, 4, and 5 students, dressed for the bush, finish their lunches and load into the school van. They are taking part in the Mother Earth Mentoring Program, a “culture-nature-awareness- experiential learning-critical thinking” program that is part of a pilot project at Waabgon Gamig First Nation School on Georgina Island. The project combines in-class learning with outdoor education, connecting the standard Ontario curriculum with First Nations ways of knowing. It has had an enormous impact not only on the students, but also on the culture of the school and the local First Nation community on Georgina Island. “Akinoomaagzid,” the traditional name of the program given by respected Elder and native language teacher Barb McDonald translates as “The Earth is our Teacher.”

The school van transports the children to one of the outdoor classrooms located on the island – places like the SugarBush Trail, the Nanabush Trails, the quarry, or the beach. This is where students’ classroom learning connects with the environment. Upon arriving at their destination, students often lay tobacco and ask Mother Earth for permission to enter the bush before they begin exploring and applying their lessons. After an afternoon of exploring, the students gather into a closing circle and give an appreciation for the day. The circle is often the most powerful moment of the day. The following day students reflect on their adventures by documenting their questions, researching the bugs they have found, writing journal entries, recording video, or making paintings.

Throughout the week, the seeds for the outdoor lessons are planted in the classroom. Two classroom teachers, an amazing team of support staff, parents, community members, Elders, and Coyote Mentors (from the Stick and Stones Wilderness School and Earth Tracks) spend their days planning, evaluating, assessing, and documenting the program. A strong academic morning with math and literacy blocks, is followed by afternoons in the outdoors. Curricular expectations in science, social studies, arts, health, and physical education are integrated into the afternoon program, and are often linked into the morning block by literacy, real-life math problems, hands- on projects, and classroom discussions. For instance, when students study Canada and the World, they learn the basics of mapping in the classroom. Then while in the bush, students create a “songline” of key features along a trail that will help them map their base camp in their mind’s eye. Students learn basic mapping skills in a way that engages multiple intelligences.

Differentiated instruction is at the forefront, and the practice of critical inquiry has become second nature to students. Shy students become leaders, weak writers become reporters, busybodies become photographers, and the students who dislike insects and mud go home filthy with a “bug box” to share with their families. Because everyone has a role, everyone is successful. This tiny waterfront community houses phenomenal stands of butternut, an endangered species, and an abundance of flora and fauna, many of which are considered species at risk. Learning outside on the earth’s blanket provides students with the opportunity to see, feel, hear, smell, and sometimes even taste their learning.

It is these hands-on experiences and personal connections to learning that keep students excited and engaged. Everyone has the opportunity to discover their unique gifts and these are celebrated both in and out of the classroom. Parents report that rather than running to the TV or video games after school, their children are doing Google searches on life cycles and habitats, or trying to identify the strange creatures that made their way to the kitchen sink. A student who was struggling with writing brought journals with detailed drawings of salamanders and snakes he had discovered on an outing to school. Another student who had been fearful of creepy-crawlies, volunteered to take an unknown swimming creature home to research what it was. These anecdotes about the MEM program demonstrate that something magical is happening. We are creating bright-eyed learners who are passionate to find answers to their daily wonderings.

Besides, the standard provincial school curriculum and standard educational practices have not served First Nations students well. Waabgon Gamig is not striving for the same education or same results. The school strives for results that exceed provincial school counterparts. A recent federal government report reveals that the 2009–2010 national graduation rate for First Nations reserve students attending provincial schools is 39 percent. For the province of Ontario, the rate is lower, at 33 percent. These statistics speak volumes about the need for differentiated, creative, and engaging programming for our students. If we can get them excited about learning at the elementary level, their chance for school success will improve. Students encourage each other to face their fears in this supportive environment, raising self-esteem while building a community of learners through hands-on, minds-on, outdoor experiential education.

Having people in the community serve as resources is like having 100 encyclopedias of cultural and traditional knowledge at your side. Local experts such as biologists and environmental coordinators are regular guests to the school. Local Indigenous knowledge is also cultivated through community luncheons, parent conferences, and mainland visitors. A sense of stewardship and pride across generations has evolved through the involvement of parents and community members as they share their specific knowledge and stories of the land. They bring their expertise and knowledge to the school, thus propelling the preservation and renewal process of intergenerational learning and teaching. Archaeology, soapstone carving, quill work, beading, painting, and traditional teachings about food, fire, sweat lodge ceremonies, and the rites of passage are just a few of the learning experiences embraced by all.

In addition, a wide variety of professional resources such as Nature’s Curiosity, Project Wild, Below Zero, and Coyote’s Guide to Connecting with Nature help ensure academic standards of teaching, learning, and assessment are met. Using Harvard University’s “Making Thinking Visible” framework for assessing students’ thinking has also been something new for the team at Waabgon. Gone are the days when students were assessed on regurgitated information. That’s for the birds.

The ultimate question remains: Is a program like this possible in a “regular” school? The pupil–staff ratio at Waabgon is utopian and certainly a program to promote nature awareness would be more demanding in a school with a 25-plus:1 ratio. But consider this: even in Ontario’s city schools, nature is close by. Many schools have ravines or parks or woodlots or fields within walking distance. The diversity of ecosystems may be limited, but even one of these locations can provide the space to follow most of the 12 core routines outlined in Coyote’s Guide – a place for students to have the opportunity to listen and learn about bird talk, to iden- tify the characteristics of an ecosystem, to wander, to identify flora and fauna, to track animals, and so on. Backyards or parks close to apartment buildings could become “sit- spots” for children where they learn to relax and observe and journal about what they see and hear and feel and find. (See Coyote’s Guide for all 12 core routines).

The rest of the planning is the same: enlisting the support of the administration to leave the building, getting parents on board and perhaps volunteering, teachers as well as kids putting on weather-appropriate outdoor clothing, and getting dirty out there. Plan to be patient and persevere in order to see those behavioural changes. For example, rather than smashing the rotten log to pieces, students will start to gather round and observe insects and grubs, asking questions and wondering with bright eyes. If all else fails or the weather doesn’t co-operate, bring nature inside. Load up your room with plants and ask the caretakers to water them on school break. Bring in fallen nests, an assortment of leaves, milkweeds, or pictures from your own environmental excursions. Your Brain on Nature: TheScience of Nature’s Influence on Your Health, Happiness and Vitality by E. Selhub and A. Logan might provide the facts and figures you need to convince those who hold the pursestrings and/or make the rules to let you leave the building often, and in all weathers.

Finally, the overall goal of Waabgon Gamig and the Mother Earth Mentoring Program is to assist students in becoming environmentalists and critical thinkers for twenty-first-century learning.

Our learning journey for today ends with this: One day while out for a walk in the trails with the curator of amphibians for the Toronto Zoo, one of the kindergarten students considered taking a salamander home. The student pondered and then changed her mind. She hesitated and then said, “No – the salamander doesn’t belong to me, it belongs to the Earth.” So what are you waiting for?

Get out your rubber boots!