Speaking to Mental Health

This Q+A between an ETFO member and two staff hilights the stigma around mental health, successful strategies and supports, feeling “normal,” student’s mental health issues and how to support colleagues.

Tell us about your personal journey. What challenges did you face? How did you deal with them?

The biggest challenge was getting a diagnosis, and then a treatment plan. I was 31 years old before I was given the diagnoses of Bipolar Disorder and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. The years before then were chaotic, unhappy and, at times, very dangerous, as I caromed between mania and severe depression and lacked judgment around the things I should be doing and the people I should be doing them with.

What eventually happened is that my family doctor diagnosed me as depressed and gave me an anti-depressant which pushed me through the roof into a psychotic mania. I was quickly referred to a psychiatrist, and the diagnosis then was easy. The accompanying diagnosis of PTSD came after a few months of talk therapy.

So, I was diagnosed and started on meds in my early 30’s. It took time to find the right medications, and it took time to work through all the issues of childhood abuse that led to the PTSD. Finally, as I approached my 40’s I was stable enough to return to school, complete my undergrad and go to a faculty of education.

The big challenge for me now is to feel ‘normal.’ And when I do feel normal, which is most of the time, the accompanying challenge is for me to remember that I have a mental illness, and that I need to take care to make sure that I am sleeping and eating well, and monitor the changes in my moods. Fortunately, I haven’t been seriously ill in a very long time.

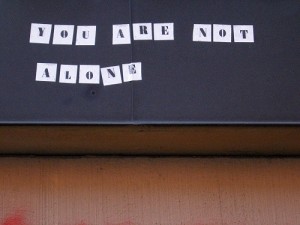

Another challenge is the stigma around mental health issues. Part of me wishes that I were able to do this article and publish my name and picture along with it. I really have been well for a very long time, and I can honestly say that my mental health does not, and has not, affected my teaching in any significant way. I know that there are plenty of good people around who would understand and accept that. But I also understand that there are many who won’t. I do, on occasion, tell one person or another, and now and then I get a really bad reaction. Some people don’t understand, and are even fearful of what Bipolar Disorder might mean. I’m concerned that some parents might not want their children taught by me if they knew

What lessons do you think can be learned from your experience?

We know now that 1 in 5 people will be affected by mental health issues in their lifetime. Talk about dealing with depression and anxiety abounds, it seems, in many school staff rooms. Mental health issues are the number one cause of LTD cases among the teaching profession. What I have in my back pocket is years of experience dealing with psychosis, mood swings, medications and psychiatrists. I know that it takes time to find out what exactly is going on in the brain gone awry. It takes good doctors, trials of meds (sometimes many trials), and willingness on the part of the patient to really dig deep and work to understand how the medications and therapy are affecting them to know when things are working and when they’re not.

I have learned not to give up. I’ve learned to keep trying, and to ask for help, when things don’t feel right with my emotional state. I’ve learned that I need to have a solid cadre of good people around me who can help me to recognize when my behaviour is starting to veer off track. And I’ve learned that the people outside of that core group do not need to know, and in many cases should not know, about my illness.

Are there strategies you would offer to teachers who may have a student who has mental health issues?

If you actually know a child has mental health issues you’re very lucky, as many children go undiagnosed until well into adulthood. The key thing to remember, I think, is that there are going to be days where just showing up for school has maybe pushed that child to their limit and that perhaps you can’t expect any more from that child for that day. Take the time to acknowledge that troublesome emotional states can be very real to the child. If a child is constantly crying, or just slumping over their desk, or obsessing over something or even yelling at you, acknowledge how they feel, and help them to realize how they feel. Self-awareness takes time to cultivate, especially for a child, yet it is key to recovery from mental illness, and a willing and observant teacher can support a child in developing it. A helpful resource for teachers is the ABCs of Mental Health Website.

If you could leave others with a message based on your experience, what would it be?

Learning to live a productive and happy life with mental illness is very possible. In my case, I know that I will always have Bipolar Disorder, but that doesn’t mean that I have to suffer the highs and

lows of mania and depression. I pay careful attention to my moods, and stop the cycles before they get out of hand, and I’m getting better and better at that as the years go by. Build a good

team around yourself, and get a good, knowledgeable doctor, preferably a psychiatrist. Ask for accommodations at work, if you need them, but before you do that, seek help from your local in knowing what medical information you are going to need to provide to your board, and what should remain confidential.

How would you like to see educators respond/interact with colleagues who have mental health issues?

It is important for people to see past the stigma. If one in five of us is going to deal with mental health issues at some point, then that means that there are likely people in every school who are dealing with mental health issues. Recognize that these are in fact medical illnesses, and that we can’t just “snap out of it,” or count on the fact that “it will be better tomorrow.” Personally, I would like my colleagues, if they knew, to recognize how stable I am now, and that having Bipolar Disorder does not mean that I am dangerous, or unbalanced or somehow ‘less than’. I have an illness that is well managed, yet that sometimes makes things more difficult for me. It has also deepened my understanding of my own emotions, and, consequently, of the emotions of the people around me. It makes me a better teacher because I have a deeper knowledge of and empathy for, the emotional states of my students. Being bipolar is not something I would have chosen for myself, but the illness and I have come to some terms of peace, and I’m somehow grateful for the lessons I’ve learned.

The author has been teaching for 9 years in small rural schools in northern Ontario. Her first years were spent teaching primary and kindergarten, which was wonderful, but she is now happily ensconced in the world of special education, where she often gets to work with students dealing with mental health issues.

This feature story is a Voice online exclusive.