Towards a Hopeful Future: In Conversation with Cindy Blackstock

You have just won a major victory at the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. Can you give our readers an overview of the decision?

On January 26, 2016, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) issued its decision that the Canadian government, specifically the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs (INAC), is racially discriminating against 163,000 First Nations children and their families by providing flawed and inequitable child welfare services (First Nations Child and Family Services Program) and by failing to implement Jordan’s Principle to ensure equitable access to government services that are available to all other children in Canada.

Jordan’s Principle specifies that the government organization first contacted regarding services for a First Nations child should pay for the service – ensuring that children are not left waiting for the services they need while governments argue over who should pay for them.

The Canadian Human Rights Tribunal made four immediate orders regarding the discrimination perpetuated by the First Nations Child and Family Services (FNCFS) Program. First, INAC was ordered to:

- Cease its discriminatory practices regarding the FNCFS Program;

- Reform the FNCFS Program;

- Cease applying the narrow definition of Jordan’s Principle; and

- Take measures to immediately implement the full meaning and scope of Jordan’s Principle.

Three months later, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal made a further order regarding immediate relief measures. This order, released on April 26, 2016, expresses concern about the government’s slow pace implementing the January ruling and issues an order requiring the federal government to apply Jordan’s Principle to all jurisdictional disputes (including between federal departments) involving all First Nations children by May 10, 2016. The federal government was also required to provide detailed information to the CHRT as to how it has complied with the Tribunal order on child welfare funding by May 26, 2016.

The Tribunal’s decision was a victory for First Nations children and all Canadians who believe in love and fairness. But implementation of the decision is key and, as the Tribunal noted in its April decision, progress has been slow.

What prompted you to take your case to the Human Rights Commission in the first place?

In Canada, provincial/territorial child welfare laws apply both on and off reserves, but the provinces and territories expect the federal government to pay for services on reserves. When the federal government does not do so, or does so to a lesser standard, the provinces do not typically top it up. This results in a two-tiered child welfare system where First Nations children receive inequitable services.

After a decade of joint work between First Nations and INAC to document the inequalities in child welfare services and to develop solutions to redress them, the federal government chose not to fix the problem. The complaint was filed as a last resort to bring the government to account and to make sure that First Nations children and families have access to equitable services compared to the rest of children living in Canada.

In 2007, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations filed a complaint pursuant to the Canadian Human Rights Commission alleging that the federal government, as represented by the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs (INAC), discriminates against 163,000 First Nations children by providing flawed and inequitable child welfare services and failing to properly implement Jordan’s Principle.

What do you think the decision will mean for First Nations children?

The CHRT decision is legally binding on the government so it should result in equity in child welfare services that takes full account of the historical disadvantage and unique cultures of First Nations children and families. It is also a watershed decision that should inform redress of inequalities across all areas of children’s experience including education, health care, early childhood education and basics like water and housing. While the government has made some statements that are encouraging, we must measure change at the level of children, and thus far, nothing has substantially changed for First Nations children and families on the ground.

I think it is vitally important that everyone understands that in this case. And it’s true in education as well; the federal government has known that their funding and policy regimes were inequitable and contributed to profound disadvantage for First Nations children for decades. Repeated solutions to address the inequalities were developed, often in partnership with the federal government, but never implemented. This is a key area for study. When I survey the literature on the disadvantage of First Nations children much of it focuses on the children, but I think there needs to be significant study and debate on why Canada has repeatedly failed to do better for First Nations children.

Can you speak specifically about the impact this decision will have on education?

The facts in the child welfare case closely mirror those in First Nations education, so it sets a strong precedent, and it is critical that people educate themselves on the inequalities in First Nations education and school funding and leverage the decision as a tool for redress. This means awakening our conscience to see the egregious harms of systemic discrimination and aligning the weight of our efforts with the severity of the problem.

Alex Sims reviewed First Nations education in a 1967 report prepared for the Department of Indian Affairs. Sims noted the inequitable education outcomes for First Nations students and the utter lack of cultural content that reflected the First Nations experience. He went on to recommend First Nations control of education and redress of the systemic underfunding of First Nations education by the federal government. That report was written some 49 years ago and little has changed. We have normalized systemic racial discrimination against First Nations children so deeply that the gravity of this injustice no longer sends shivers up the spine of the Canadian consciousness. One of the key things we need to do to address the inequalities across all areas of First Nations children’s experience is to reject notions of what I call “incremental equality.” Incremental equality is when cross-cutting and deep inequalities are dealt with one topic at a time. Although some measures are taken to address the problem, these fall far short of what is required. Defenders of incremental equality often say things like “the government can’t fix this overnight” or “these are good first steps.” The problem with incremental equality is that children do not have incremental childhoods and as Sims’ report shows us – equality never comes one drop at a time. We must achieve equity for First Nations children across all areas in a leap not in a shuffle.

What are your priorities for change for First Nations children? How will more money make a difference? What else needs to be done?

My priority? Equity across all areas of childhood for First Nations children. As former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Frankfurter noted, “There is no greater inequality than the equal treatment of unequals.” This means that equity must take into account the multi-generational harms related to colonization and the ongoing discriminatory service provision by the federal government. As Sims noted nearly 50 years ago, it also requires that curriculum and those who teach it take positive measures to ensure First Nations histories and realities are meaningfully included throughout the education system. This would benefit First Nations children and also non-Aboriginal children who have been denied a proper understanding of how contemporary realities are shaped by Canada’s longstanding discrimination against First Nations so that they can become positive co-actors in the implementation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Action.

ETFO members teach in public elementary schools in Ontario. What would you tell them about welcoming First Nations children in their classrooms?

Learn about First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples yourself and then integrate this knowledge into the classroom environment for all students. Project of Heart (projectofheart.ca) offers educators excellent tools and curriculum ideas and we also have excellent resources on our website, fncaringsociety.com, to engage students in addressing inequalities in First Nations education (Shannen’s Dream), child welfare (I am a witness) and access to public services (Jordan’s Principle).

Along with the summary of the TRC’s final report, I recommend that educators read the summary of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) and a book by historian John Milloy entitled A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986. Milloy’s book tells the story of residential schools from the perspective of the Government of Canada’s own documents. It dispels the myth that people of the period did not know better so could not do better, and provides an excellent basis to critically examine the contemporary relationship between First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples and the federal/provincial/territorial governments.

It is vital that we equip students with skills to engage in active citizenship. That means we need to provide them with opportunities to understand contemporary injustices and give them opportunities to peacefully and respectfully engage in positive change. The Caring Society hosts a number of activities every year such as Have a Heart Day where students write letters to elected officials so that First Nations children have an equal chance to grow up safely at home, get a good education, be healthy and proud of who they are. Knowing is not enough and caring is not enough; we must teach children to take action.

Are there things ETFO members could be doing to support teachers and children in First Nations schools?

Yes, bring Project of Heart to your school and get involved in Shannen’s Dream and the other campaigns at the Caring Society. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission listed child welfare, Jordan’s Principle and equity in education as its top Calls to Action so these campaigns are easy ways for students to engage with reconciliation. Also check out the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation website (http://umanitoba.ca/nctr/).

On your website you have a list of seven ways we can make a difference. Do you have anything you would add to that list when you are speaking with teachers? When you are speaking to our union?

It is critical that we emphasize that crosscutting equality is needed. Canada cannot meaningfully engage in reconciliation until it stops discriminating against First Nations children. Although the on reserve funding inequalities cited in the CHRT decision only apply to First Nations on reserve, it is also important to reach out to the Inuit and Métis communities for ideas on what can be done to support their children too.

The real hope for First Nations children does not lie with the government, it lies with caring Canadians learning about the inequalities and no longer tolerating them. That is why the work of educators is so key. Together we can raise a generation of First Nations children who do not have to recover from their childhoods and a generation of non-Aboriginal children who do not have to say they are sorry.

Do you have any final things you would like to share with our members?

In the words of Wesley Prankard, a non-Aboriginal youth and founder of Northern Starfish, “DO SOMETHING.”

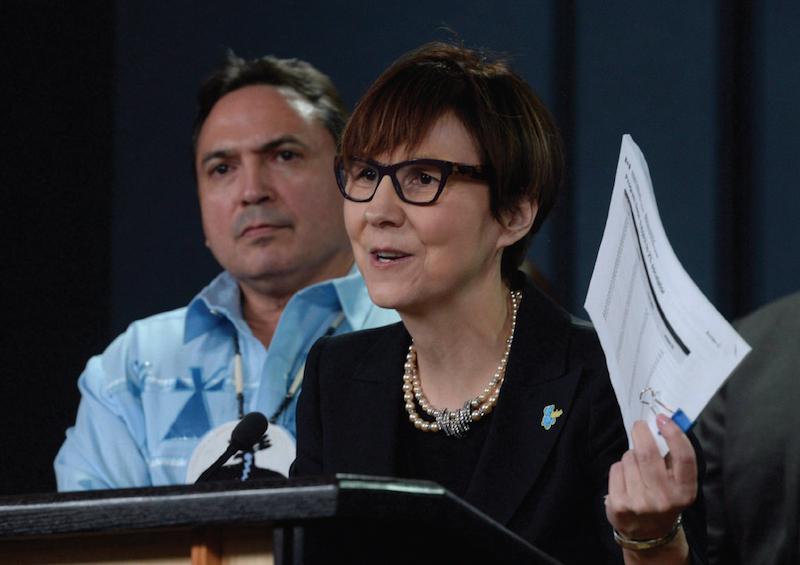

Cindy Blackstock is the Executive Director of First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, Associate Professor at the University of Alberta and Director of FNCARES. A member of the Gitksan First Nation, Cindy has 25 years of social work experience in child protection and Indigenous children’s rights. Her promotion of culturally based and evidence informed solutions has been recognized by the Nobel Women’s Initiative, the Aboriginal Achievement Foundation, Frontline Defenders and many others. The author of over 50 publications and a widely sought-after public speaker, Cindy has collaborated with other Indigenous leaders to assist the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child in the development and adoption of a General Comment on the Rights of Indigenous children.