Women Helping Women: Books to Bars

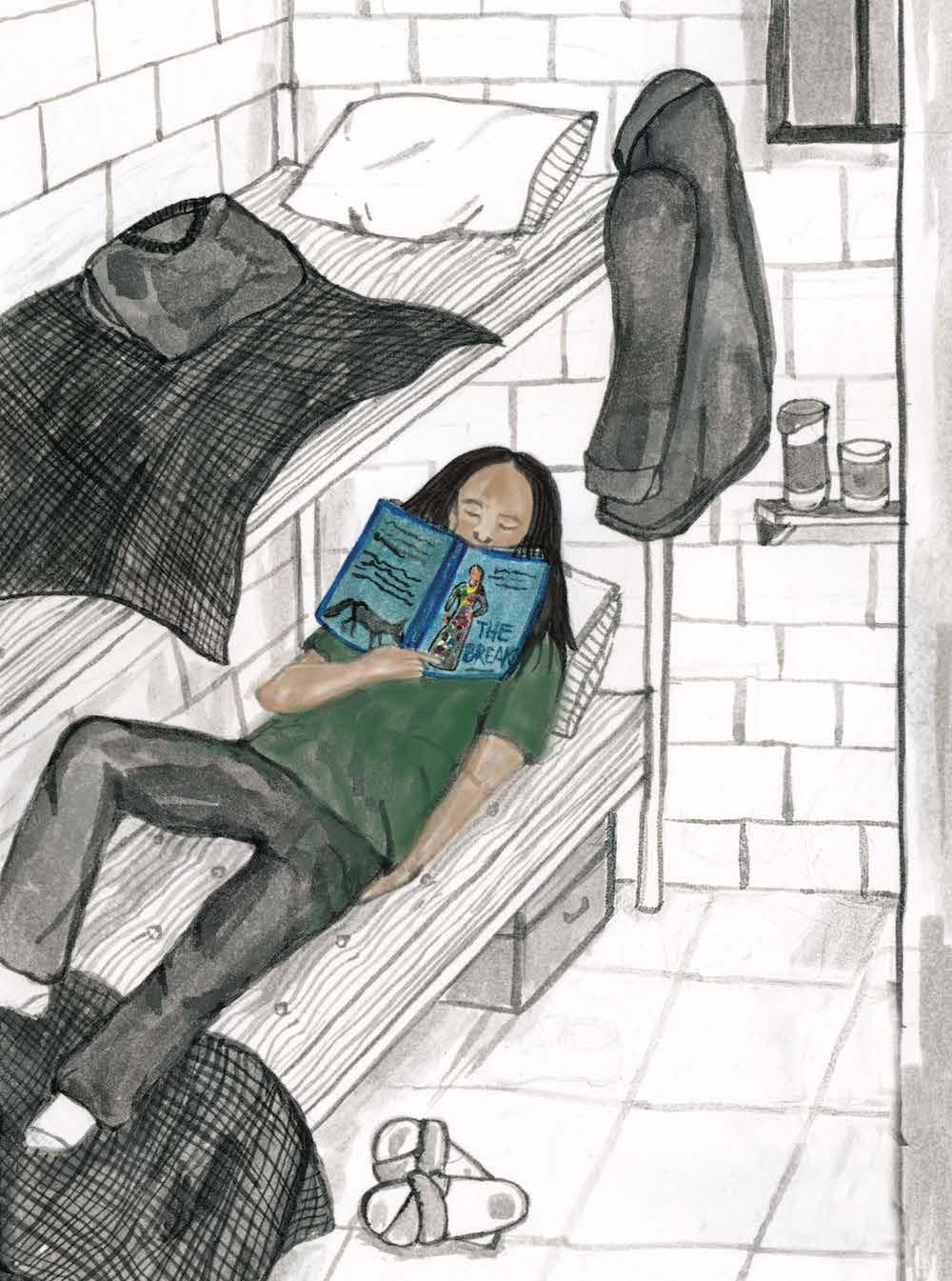

For me, teaching and activism go hand in hand. Coming to teaching as an activist took some adjusting. I had to learn to strike a balance. Traversing a growing network of organizations that became familiar to me through my union activism and teaching, such as my local Labour Council, the Sexual Assault Centre, Elizabeth Fry Society and Children’s Aid Society, I became interested in working with one of the most marginalized groups I was learning about, imprisoned women. Eventually, I found Books to Bars. Through the organization, I found a role as a volunteer in the local detention centre, working to build a lending library of donated books, tutoring women prisoners and eventually facilitating a book club. It is interesting work I do for a few hours every week. I use my skills as a trained teacher and my experience as a teacher-librarian in my activist work. I enjoy the confluence very much.

Books to Bars was founded through the hard work of a young woman we believe to be wrongfully imprisoned, Nyki Kish. (The details of her case are explained in freenyki.org). Kish became aware of the paucity of books in prisons and determined to find a community solution to this problem. She put out feelers asking for books (e.g. approaching a library in Burlington for their weeded books, friends and family) and then she hit upon the idea of starting a book drive in Hamilton. This was essentially how the organization started. She went on to host musical fundraisers that helped spread the word among activists in the city.

Like most people, I was aware of issues of mass incarceration in the United States, the disproportionate representation of racialized people and concerns over privatization and profit motives. What I learned was that these are pressing issues in Canada as well. Under Prime Minister Harper, Canada began expanding the corrections sector. While crime was down, the Harper government dabbled with public/private partnerships to bring corporations into the affairs of Corrections Services of Canada (CSC) while at the same time cutting valuable programs such as inmate farming programs and prison libraries. Like veteran teachers in Ontario who point to the Harris years as an era of repeated blows to the education sector in the form of punishing cuts to programs and budgets, workers in the corrections sector point to the Harper years as the time when the role of a trained librarian, a budget for books, a dedicated space for a library and regular programming for inmates became things of the past in many prisons.

Because of the valuable contacts Nyki established with her dedication, and a little bit of name recognition, Books to Bars has been called upon to remedy a problem that embarrassed the brass in some southern Ontario jails and prisons.

The scandalous reaction to G20 protesters in June 2010 put thousands of people in detention. One of those people was an activist who happens to be very vocal and savvy in the use of social media – his name is Alex Hundert.

From The Toronto Star, December 26, 2012:

Inmates at Toronto West Detention Centre have been denied books for much of the last two years because a volunteer who ran the library retired.

At the Toronto East Detention Centre, library service has been sporadic for 16 years because of a lack of volunteers, said Brent Ross, a spokesman for the Correctional Services ministry. Student volunteers have filled in occasionally during the last two years, he said, adding that jails have relied on volunteers since 1996 when the province laid off all librarians in correctional institutions.

The locked-up library carts came to light when Alex Hundert, jailed for his role as an organizer of the G20 protest two years ago, wrote a blog this week about not being able to get a library book at Toronto West.

“Other than a few Bibles and Korans I haven’t seen a book since I got here,” wrote Hundert, who was sentenced June 26.

“When I requested to have the library cart sent to the range so I could borrow a book, the guards told me they haven’t seen the cart in ages.”

Hundert said he was told the last time a student volunteer was delivering books was about four or five months ago.

“Since then, those of us locked up here, most not yet having been convicted of any crime, have had no access to books to read.”

Hundert used his blog and then the national press to send a message out to millions of Canadians that there is a significant problem in Canadian detention centres. This made a big difference in our ability to offer books to prisons and jails in the region. Suddenly people were talking about the austerity cuts that had obliterated this service nearly 20 years before. Ironically, this occurred because a vocal, politicized person (jailed for protesting a new austerity agenda) marshalled his resources to get this information out. The timing was critical.

Books to Bars gained more traction when it was asked to support a program called Read Aloud at the Grand Valley Institute for Women. This program connects incarcerated mothers to their families on the outside, using books. Books to Bars was asked to guarantee the delivery of 10 to 12 brand new, high quality picture books each month. The institution’s volunteers help record the incarcerated mothers reading the picture books. The digital recording is burned to a compact disc and it and the book are mailed to the family of the woman who made the recording. A book connects this family; hearing and reading along to a good book could potentially help sustain a relationship under duress.

I thought this program would be a natural fit with elementary teachers. It seemed obvious to me, as a member of Books to Bars, that I had to ask my union for help. Who would understand the power of a read-aloud better than a group of teachers with a social justice mandate? We approached the Hamilton-Wentworth Elementary Teachers’ Local executive for support and, predictably, they understood that this is an initiative that makes sense for a union committed to justice and equity. Other locals such as Peel and Hamilton DECEs have made significant financial contributions. Donations have come from OPSEU and UNIFOR locals as well. Literally hundreds of books (dual language books, books focused on FNMI themes, classics like the often-requested Love You Forever by Robert Munsch) have now worked their way from the desks of Books to Bars to the Grand Valley Institute for Women and into the hands of children missing their moms.

The conditions at the Grand Valley Institute for Women are still harsh. The suicide of Ashley Smith, a teenager who died by self-strangulation on October 19, 2007 while under suicide watch in custody and the inquest into that heartbreaking case revealed a young woman with serious mental health issues whose problems only escalated in the judicial system. Details about discrimination against LGBTQ prisoners are revealed in Nyki Kish’s blog, changeandprison.wordpress.com/, and the 2013 exposé by CTV’s Abigail Bimman paints a frightening picture of a place that houses over 200 women in various security levels. The women in this facility will rejoin their communities at some point – 85 percent of them are serving sentences of 10 years or fewer. Abolitionists and prison reform activists both agree that conditions such as these serve to alienate and test the limits of imprisoned women rather than address the issues that brought them into conflict with the law. Our work to bring books to incarcerated mothers is a heartwarming story, but just a drop in the bucket of change that must occur in that institution.

The work of Books to Bars continues to expand and evolve. When once we asked businesses to host a donation box so that customers could bring their gently used paperbacks in, we now have a new focus. We raise money to purchase what is needed. Instead of fretting over the large numbers of romance novels and spy novels based in Soviet Cold War era, we try to gather books that are more useful and respond to the needs and desires of incarcerated people in southern Ontario. When the South Detention Centre became aware of our willingness to listen directly to their needs, they indicated that many men were working on courses and needed dictionaries. We raised hundreds of dollars to purchase quality paperback dictionaries and thesauruses. When the Pittsburgh Institute (in Kingston, Ontario) was trying to support an inmate who needed a classic Russian novel in the original Russian, we located a copy and shipped it as soon as we could. Recently, a nurse at the Brockville Jail decided to seek Books to Bars out when she realized inmates there had virtually nothing to read. We shipped a selection of books immediately. FNMI women are disproportionately represented in jails and prisons. The CBC reports that they represent one third of all female prisoners. Like all readers, they are looking for books in which they can see themselves represented. We constantly scour used books stores and place orders for new books to meet this need.

How Books to Bars tackles the problem of a lack of access to quality reading material has changed; rather than sending along those gently used books, we have tried to make our focus sharper and more purposeful. Collecting the important information about what is needed remains a difficult task. We rely on the relationships we have developed with Correctional Services staff and rarely hear directly from the readers. The people who have volunteered for the organization have mostly stayed but some have moved on. How we fund ourselves, however, remains consistent. We look to organizations with a commitment to equity and we find them, thankfully, in the labour movement.

Francesca Alfano is a member of Hamilton Wentworth Teacher Local. Follow Books to Bars on twitter @bookstobars.