15 Years In: Unpacking DECE Reflections and Realities

The 2025-26 school year marks 15 years of Full-Day Kindergarten (FDK) in Ontario and the integration of early childhood educators (ECEs) into the public school system as designated early childhood educators (DECEs).

The road map for FDK grew out of extensive consultation and input from education experts, including Charles Pascal’s 2009 report, With Our Best Future in Mind. Grounded in developmental neuroscience and global research, this report recognized the profound impact of high-quality early years programs on brain development and lifelong social, emotional and cognitive growth, and emphasized the vital role of ECEs in delivering quality educational programs.

FDK introduced a co-teaching model, pairing a teacher and a DECE to deliver a play- and inquiry-based program. This marked a significant shift from previous Kindergarten approaches that leaned towards structured, teacher-led lessons focused on academic readiness. The new model reiterated play as a key learning process, essential for developing problem-solving and cognitive skills, resilience and social-emotional growth across multiple domains.

The History and Science of Play

Modern education is grounded in the contributions of scholars such as Froebel, Dewey, Vygotsky, Piaget and Montessori, who conclusively demonstrated that learning is most effective when it is experiential, child-centred, inclusive and rooted in social interaction and discovery. Central to their work is the recognition that play is not a recreational add-on, but the foundational mechanism through which children engage in knowledge construction, meaning making and development across multiple domains: cognitive, social, emotional and physical.

Play is recognized as the highest expression of human development, enabling children to explore, create and communicate within environments designed to support their growth. When thoughtfully and democratically constructed to foster curiosity, inquiry and interaction, the learning environment itself acts as a “third teacher,” shaping opportunities for creativity, exploration and meaningful engagement. This reflects a broader commitment to children’s rights and participation, recognizing that children learn best when they are active contributors to their own learning.

Dewey emphasized that democracy in education requires the inclusion of all voices, ensuring that individuals, including children, are active participants in shaping their learning experiences, a vision echoed in Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which affirms that children have the right to express their views and have those views respected in decisions that affect them.

Collectively, these perspectives have shaped modern educational practices, affirming that when learning is experiential, play-based and inclusive, it fosters not only academic success but also children’s overall well-being and sense of agency.

The Continuum of Play: Misunderstood and Off Track

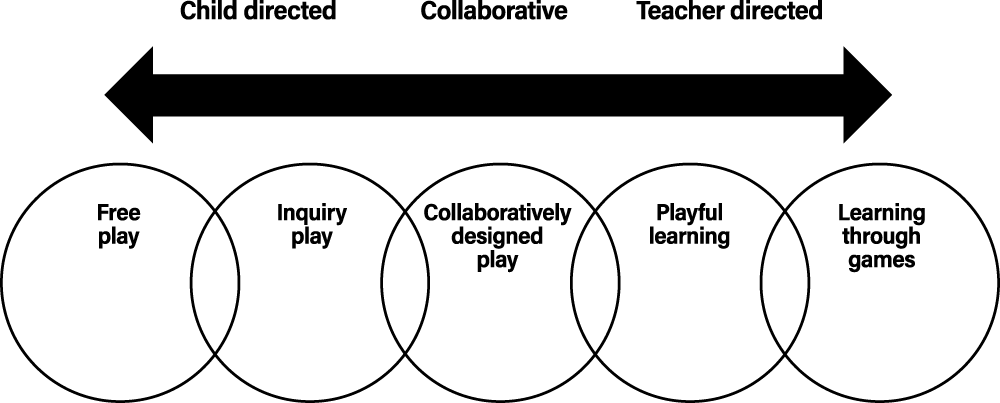

Play is often misinterpreted, making it essential to distinguish between free play and play-based learning. Free play, typically child-directed, emphasizes enjoyment, active engagement and process over outcome. In contrast, play-based learning integrates academic concepts into play in a developmentally appropriate way, building on children’s interests and ensuring learning remains meaningful and enjoyable. This approach moves beyond the outdated divide between play and learning by incorporating varying levels of adult involvement to support academic growth within a playful, child-centred context. Play is not only a tool for social and emotional development but, when thoughtfully integrated, a powerful avenue for academic learning.

To effectively scaffold and extend learning, educators must engage and play alongside children, questioning, guiding and challenging their thinking to support attention, self-regulation, emotional awareness and academic skills. Yet, increasing pressure for academic accountability has shifted the focus toward standards and assessments that reflect the broader trend of “schoolification,” in which early learning begins to mirror formal schooling, narrowing the focus to academic achievement at the cost of holistic development.

Schoolification of the Early Years

The term schoolification, spotlighted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s 2006 Starting Strong II report, describes a growing global concern in which early years programs and primary education begin to look and feel more like traditional or formal modes of education before children are developmentally ready. Instead of prioritizing play, exploration and hands-on learning, there is increased pressure for reading, math and more adult-led activities, like long carpet times. As a result, culturally rich, purposeful play is often reduced, and academic work takes centre stage. Play is reduced to a reward for completing “real work,” rather than being recognized as meaningful work and essential learning in itself.

At its core, schoolification reflects a top-down approach where children are expected to get ready for school, instead of schools being ready for children, imposing the idea that children must become something, rather than simply be!

As Ontario awaited the update to The Kindergarten Program (2016) this year, the government quietly announced on the last day of school that the revision would be postponed and released in 2026, citing the need to give educators more time to prepare.

The proposed curriculum places significant emphasis on direct instruction in reading, writing and math. Mandatory learning expectations include structured literacy instruction, with educators encouraged to introduce vocabulary during play, and direct instruction in numeracy, alongside daily opportunities to explore math through playbased learning. While the government insists this approach will strengthen academic foundations without compromising play, the repeated “back to basics” tagline has only deepened concerns among experts, who question whether these changes reflect a genuine, child-centred commitment to learning or simply repackage academics under the language of play.

Child psychiatrist Dr. Jean Clinton has expressed concerns about the potential schoolification of FDK under the proposed curriculum, emphasizing that educators need to support both academic success and well-being by guiding inquiry- and play-based activities alongside some direct instruction. Clinton, an adviser to the Ontario government on education reform from 2014 to 2018, cautions that nothing is more fundamental than protecting children’s right to play, and warns that a decline in play in favour of structured, academic approaches could contribute to rising mental health challenges in children.

These concerns underscore the critical role of quality in early years programs. Programs led by trained educators and supported by inquiry- and play-based curriculums that prioritize children’s agency are hallmarks of high-quality education, fostering lasting benefits for children. When these elements are neglected, children may experience developmental delays and emotional distress, with negative impacts that extend far beyond the early years and carry long-term societal costs. Behavioural challenges are often shaped by reduced play, limited student belonging and agency and program quality, reminding us that when these factors are overlooked, they can quietly contribute to the mental health struggles children face, which may surface over time as increased behavioural concerns and escalating violence in schools.

With “COVID babies” now in schools, a more informed and proactive government strategy would embrace a “back to the future” curriculum, one grounded in lessons gleaned from the past, including the need for explicit social-emotional learning. This requires recognizing that the development of executive functioning and self-regulation skills is the foundation upon which academic learning must be built, not the other way around. Supporting these critical developmental foundations is at the core of the FDK model.

The Teacher-DECE Partnership

FDK was intentionally designed to bring together two complementary professionals: teachers, with expertise in curriculum and assessment, and DECEs, with specialized knowledge in child development, observation and pedagogical documentation. In Kindergarten, the classroom teacher and DECE work as a team to bring the program to life. Although DECEs have been part of the school system for 15 years, they still face ongoing systemic challenges that may affect their job satisfaction and overall sense of self-efficacy. Many DECEs talk about feeling unheard, with decisions made for them rather than with them. Common concerns include being treated as assistants, having limited planning time, few mentorship opportunities, minimal access to meaningful professional development and the absence of clear pathways for growth, leadership development and career mobility. These conditions contribute to ongoing inequities and professional marginalization.

The Ontario Ministry of Education defines equity as “fair, inclusive and respectful treatment of all people,” which acknowledges that equity requires addressing individual differences, not treating everyone the same. Marginalization is defined by UNESCO as a “form of acute and persistent disadvantage rooted in underlying social inequalities, which disproportionately affects women, Indigenous Peoples and ethnic minorities.” Even after 15 years of ECEs in the school system, most boards lack clear pathways for DECE growth development and career progression, contributing to professional stagnation and reinforcing inequities. As one DECE I know reflected, “When I started at [my] school board, J. was my teaching partner. Now J. is a vice-principal I’m still a DECE in the classroom. Why have I not grown in my school board or had opportunities available to me?”

The Job of Leaders

True leaders create more leaders, not followers. ETFO recognizes both the invaluable contributions of DECEs to children’s holistic development and the importance of advancing women in leadership. By developing programs specifically designed to uplift women, ETFO sets a strong precedent for leadership growth within education. Initiatives such as Leaders for Tomorrow, An Ounce of Prevention, Presenter’s Palette, and Visions, and Leads, alongside programs focused on union advocacy, communication and leadership, exemplify this commitment. True leadership means forging pathways where none exist, creating space for others to thrive, succeed and lead, lifting as we climb, ensuring no one is left behind.

Like the roots of a tree, the early years anchor everything that comes after. A strong and equitable education system cannot be built without prioritizing the early years, and the educators who shape them. Kindergarten and early childhood education are where educators lay the groundwork for children’s lifelong learning, well-being and citizenship. There is enough compelling evidence that investment in high-quality early years education is essential, not only to expand access, but to ensure quality. That quality depends on a well-supported workforce.

A balanced, evidence-informed early years policy must centre children’s rights, play and the deep expertise of practitioners. Smaller class sizes, inclusive environments and access to mental health and special education supports empower educators to meet every child’s needs. DECEs must be supported through sustained professional learning, fair remuneration, and clear career pathways into mentorship and leadership.

Getting it right from the start is easier than fixing problems later. To build a sound and sustainable future, the government must invest in Ontario’s youngest learners, public schools and the early years workforce. A truly sustainable education system depends on seeing and supporting both children and the educators who guide and nurture them.

Samia Javed is a member of the Hamilton-Wentworth DECE Local.