Flamingo Rampant

About 12 years ago, I was working in the library of a middle school when I was pulled into a conversation with another teacher and an administrator. The former had told the latter that my library was in possession of a title that might not be appropriate for adolescent readers. I presume the purpose of the meeting was to bring me to my senses.

Here’s how it went. The offending title was a benign little picture book called Mom and Mum Are Getting Married, published in 2004. In the exchange, there was much hemming and hawing about whether we had any “gay families” in the school, along with concerns some people of faith might be offended and recent immigrants wouldn’t understand. I stated the obvious: people can be gay (like my own late father) and parent children with a different sex spouse; children themselves might be gay or questioning, regardless of parent or community comfort levels; people of faith and immigrants are not automatically heterosexual or cisgender, nor are they automatically unaware of these issues, homophobic or transphobic. As I look back, I’m honestly embarrassed that such a conversation could take place. By the way, I stood my ground. The book remained in our library.

Back when I started in the library, Mom and Mum Are Getting Married was one of a grand total of three LGBT2Q books I was aware of. The others were Asha’s Mums (Women’s Press, 1990) and Daddy’s Roommate (Alyson Books, 1990). School and public librarians had to fight to keep these titles on the shelves of children’s libraries. The pushback was that intense.

Thankfully, j wallace skelton and S. Bear Bergman – partners in life and business – have expanded the small corpus of picture books with diverse queer and trans characters. And they’ve taken it a step further. Flamingo Rampant “is a micropress with a mission,” reads their website, “to produce feminist, racially diverse, LGBT2Q positive children’s books, in an effort to bring visibility and positivity to the reading landscape of children everywhere.” Every two years since 2015, their publishing house has released a series of six new picture book titles – the third is scheduled to launch in August of 2019. Funding for these editions has come from Kickstarter campaigns, allowing readers to pre-order the titles.

Where earlier titles painstakingly explained that gay parents were just like everybody else, Flamingo Rampant titles are unapologetically queer. A good example is The Last Place You Look (2017) by j wallace skelton. The setting is a seder at Pesach. A large extended family has gathered and is about to begin the ritual hiding of the matzo bread – a children’s game. It’s a funny, charming story of a family tradition, complicated by a misplaced matzo. Readers might even overlook that grandma, Bubbe, is partnered with another woman. Their relationship as spouses is simply part of the landscape of a family diverse in race, gender and ability.

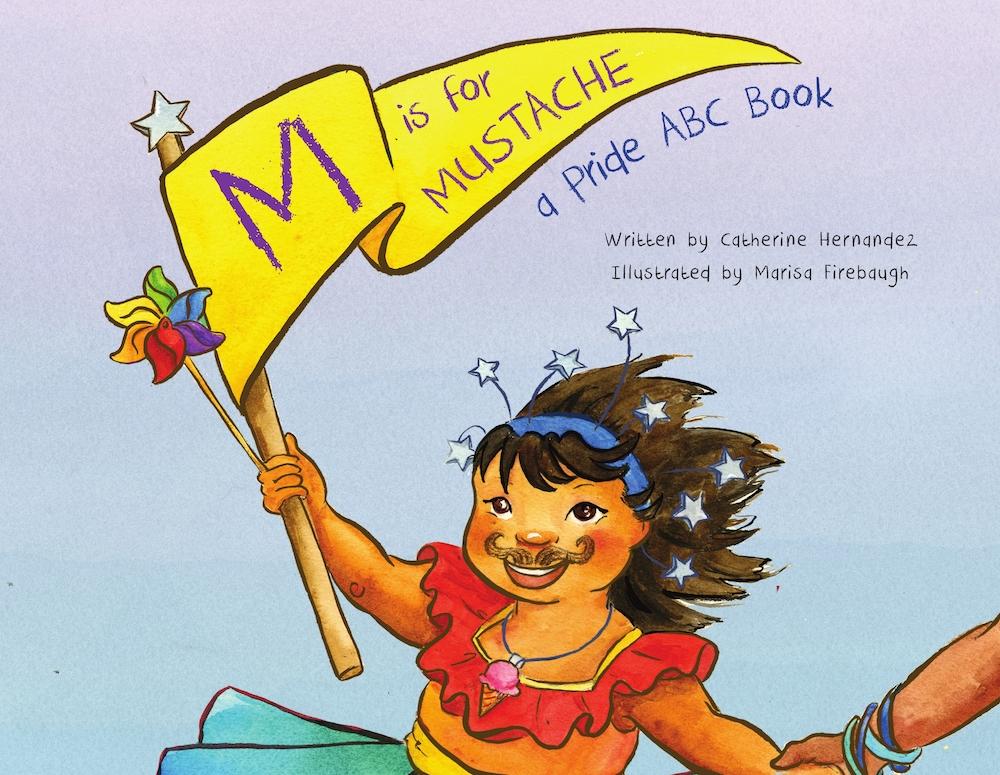

The theme of family runs through Flamingo Rampant titles. A popular entry from its first series is M is for Mustache: a Pride ABC Book (2015) by Catherine Hernandez, more recently the author of the celebrated novel Scarborough. The picture book is narrated by the author’s daughter as a young girl while visiting the Toronto Pride festival. Hernandez, a theatre artist, had taken a meeting with Flamingo Rampant co-founder S. Bear Bergman who, to her initial surprise, asked her if she had an idea for a children’s story to appear in the first season of titles.

Although she had never written a children’s book, an idea emerged. “It was as easy as breathing. When my daughter was around five years old, she was known as ‘the little tyke on a bike’ for the Dyke March,” well known for the Dykes on Bikes contingent of motorcyclists. Hernandez’s daughter, wearing a pink Stetson, would ride down Yonge Street on her little bike festooned with balloons. “You could really see in her mind that she thought she was on a float,” Hernandez laughs.

This child-like point of view is maintained throughout M is for Mustache. The words chosen for the letters of the alphabet reflect that viewpoint:

“T is for Tita, our Filipino word for Auntie, which is a kind of chosen family I am so lucky to have so many of.”

Again, this mirrors the experience of Hernandez’s family and that of many queer people. When relatives and community are unsupportive, it’s common for queer and trans people to form a chosen family, made up of peers who agree to help raise children and support one another. The several titas pictured in the book are diverse in ethnicity and gender expression.

Another example of the intersectionality of Flamingo Rampant titles is the book 47,000 Beads (2017) by Koja Adeyoha and Angel Adeyoha, with illustrations by Holly McGillis. “Peyton loves to dance, and especially at powwow, but her Auntie notices that she’s been dancing less and less. When Peyton shares that she just can’t be comfortable wearing a dress anymore, Auntie Eyota asks some friends for help in getting Peyton what she needs.”

Auntie begins to wonder if Peyton is two-spirit and seeks the counsel of an elder, referred to as “Grandparent” and “L.” It’s important to note that Peyton has not declared herself two-spirit, or trans, or non-binary. Neither have the extended family in her life. They merely respond affirmingly to her wishes and collaborate to make her a regalia similar to that worn by her brother and uncle. Auntie’s sole motivation is to support Peyton. “She feels alone but I know she isn’t. I want to show her that she’s not.”

Similarly, L’s advice is to “share [two-spirit] teachings with [Peyton], and to guide her while she learns which path is hers to walk.” Thus, being two-spirit – or queer or trans – is not a problem to be solved or a condition that requires explanation. It is a path available to the child.

This environment of supportive family and community aligns with best practice for care of gender non-conforming children. The American Psychiatric Association’s removal of Gender Identity Disorder as a diagnosis in 2013, in favour of Gender Dysphoria, has opened up affirming models of care to support children as they explore gender identity and expression. This contrasts sharply with past models that discouraged gender non-conforming behaviours. When children feel supported – not only clinically, but at home and school – healthier outcomes are expected. Essentially, the child leads the way. Caring adults and professionals provide guidance and support.

Looking ahead to August of 2019, Flamingo Rampant will be releasing The Great Space Adventure by Ryka Aoki, illustrated by Cai L. Steele, “about a non-binary kid who takes a splendid space adventure and returns home to discuss their discoveries (including that Neptune smells like farts!).” Aoki, an author and English professor at Santa Monica College, jumped at the opportunity when asked by Bear Bergman if she would like to write a children’s book for the 2019 season of Flamingo Rampant titles.

Aoki explains her interest in writing about the solar system for a children’s book about a non-binary kid: “I think it would be really nice to have a book that was a lot gentler and treated space as something homey. A lot of times kids live in a very heterocentric world, very many times a Euro-centric world. We live in an Earth-centric solar system. We portray different planets in relation to Earth. We might think about all the planets being different, and the other planets being perfectly happy with who they are.”

So Why Are These Books So Important?

Representation matters. Over the last many years, I’ve been an LGBT2Q Positive Space representative in three different TDSB elementary schools and have advised Gay/Queer Straight Alliances in two of them. In this role, I’m often sought out by queer parents or parents of queer children. These encounters can be quite emotional when parents see their families represented in literature I share in the library, the classroom or the GSA. The mere existence of these books inside a public elementary school is game changing for families who might feel marginalized.

There is also the reaction of children themselves. During Pride Month in June, which is also Aboriginal Heritage Month, a title like 47,000 Beads triggers thoughtful conversations across grade levels. Sometimes, when I share this literature, there’s just a quiet, thoughtful look from that kid who hangs out with me on yard duty, but never quite tells me what’s on their mind. Books like these are beacons to kids who feel that they are in some way different from their peers.

I believe it is the affirming nature of these titles that makes them unique and worthwhile for school libraries and classrooms. LGBT2Q themed books like Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress (Groundwood, 2014) or The Sissy Duckling (Simon Schuster Books, 2015) sometimes rely on the experience of bullying to drive the narrative. Thus, they are anti-bullying books, whose characters are defined by their mistreatment. They have a place in this canon – because bullying and mistreatment are a part of life for LGBT2Q people growing up and in adulthood – but there is room for other stories.

j wallace skelton points to his graduate research, in which j managed to unearth rare, out-of-print titles with trans and gender-independent characters going back to the 1930s! “One evening, Bear read quite a number of them to a much smaller Stanley (their older child), who eventually asked him to stop reading, because so many of the books were full of bullying, name calling and worse.”

Bear Bergman echoes the sentiment, pointing to anecdotes he’s heard of the books being used to diffuse unpleasant experiences at school. “It means there’s no negative message to try to explain or overcome, and from an educational perspective the kids aren’t learning new ways to be horrible or new unpleasant words to say.”

What About Pushback from Parents or Administrators?

This is a question I’m asked quite often, and it is a legitimate one. I think it’s very important that teachers be armed with facts and policy. Children’s gender identity and sexual orientation are not changed by reading books. Were that so, the deluge of heteronormative and cisnormative literature, such as the ubiquitous Berenstain Bears and Little Critters series that fill tubs in school libraries, would have ensured successive generations of heterosexual and gender-conforming children.

Representing the diversity that populates our schools, communities and the broader world is actually our job as teachers. Notwithstanding the blatantly homophobic and transphobic campaign against the 2015 Ontario Health and Physical Education curriculum, as well as the Ford government’s decision to withdraw it, Ontario teachers have a mandate to make sure schools are safe and welcoming spaces for all students. Specifically, under Bill 13, The Safe and Accepting Schools Act, it is the role of the school to “promote respect and understanding for all students regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability or any other factor.”

These policies are echoed by ETFO, other federations and our local school boards. I believe that teachers must be forceful in defending these policies. An example of this is found in Catherine Hernandez’s experience after M is for Mustache was published. This was in 2015, when the health curriculum – previously shelved by Dalton McGuinty in 2010 – was restored under Kathleen Wynne’s majority Liberal government. When Hernandez offered to read the book for free at a local school, she was stonewalled by one administrator who was fearful of backlash amidst the anti-sex ed protests of the time. Hernandez found support among ETFO members in local schools who pushed to bring her in after she reached out in a Facebook post.

Well-told, affirming stories, I believe, hold the promise of expanding the imaginations of children. Bear agrees: “We’re trying to improve the situation of 20 or 30 years from now, by teaching small children that LGBT2Q people exist in the world, and are lovely and fine, and get to have families and friends. Even just to be able to see a positive representation of a queer family is a very big deal. When you add that to some of what we’re able to do around bodies, ability, race, culture and other factors, it’s tremendous.”

Gordon Nore is a member of the Elementary Teachers of Toronto.