Leh We Go Befoh – Let us Move Forward

In 2008, I received a phone call from the Canadian Teachers’ Federation (CTF) to discuss the possibility of going to Sierra Leone with Project Overseas (PO). I knew very little about Sierra Leone and had only collected impressions from a few news reports that focused on the civil war. I knew I had lots to learn. Like many other volunteers, I had applied for PO because I wanted to make a difference, and this seemed like a great opportunity to learn about the host country and to share my teaching skills and experience.

Project Overseas is a joint endeavour of CTF, participating member organizations such as the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO), and overseas partners such as the Sierra Leone Teachers’ Union (SLTU). The primary focus of PO is delivering professional development for teachers in developing countries. Each Canadian volunteer leads workshops with a co-tutor from the host country. Excited to be connected with a co-tutor, I prepared for the challenge by reading, speaking with PO alumni, and organizing a binder of possible lesson plans.

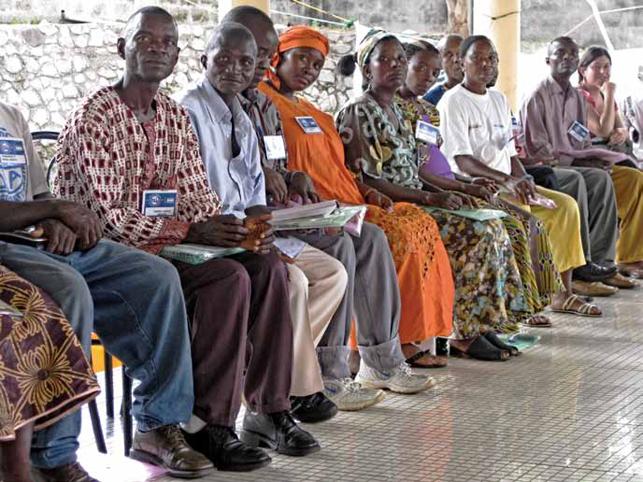

Although we had several unexpected challenges that first year, we managed to work alongside co-tutors, delivering lessons on the various workshop topics requested by the SLTU. The teachers were extremely open-minded and positive. They participated in my choral read ing lessons and morning messages with great enthusiasm. Together we tried our best to work through the tight schedule.

When I returned in 2009 as a team leader, the highlight was reconnecting with my SLTU colleagues and their families. Our team attempted to bring local resources into the workshops. We also tried to reinforce content from the various sessions to make the program more holistic. Like the summer before, my time was filled with unique learning experiences. One evening, I sat with Jacomo Bangura, a colleague from SLTU, catching up on our last year and discussing the PO program. The electricity went out, but the conversation didn’t skip a beat; we continued to talk by flashlight about the benefits and drawbacks of PO. We both had many unanswered questions about what was happening after participants left the capital city, where PO took place, for their homes in rural communities. We questioned whether they had the resources and support to implement workshop ideas. Wewondered how we could include more local ideas in future workshops and what was missing from our program. Jacomo suggested it was time for follow-up and encouraged me to come back to Salone in 2010 to undertake research that might shed light on some of these unanswered questions. This conversation and my critical reflections about PO in Sierra Leone developed into graduate research in which I followed up with past PO participants.

The Sierra Leonean educators that I interviewed reported learning skills for their class rooms, such as how to use various teaching tools and how to develop lesson plans, which in turn influenced student learning. They reported an increased understanding of SLTU and were able to clarify some misconceptions. Perhaps the most powerful finding was the social and emotional impact that PO has had on teachers’ lives. Many Sierra Leonean teachers reported an increase in self-confidence and expressed the intention to pursue post secondary studies.

I have found various practices within the structure of PO that work toward a frame work that puts the host country at the centre, including co-tutor partnerships, the practice of sending repeat volunteers, and CTF’s effort to meet partner requests. From my informal conversations with PO alumni and my own experiences, it is clear how committed, well intentioned, and passionate PO volunteers are about the work they do. We are excited to learn from, with, and about our colleagues.

Despite the success, I had many lingering questions about how better to enable PO to work toward a framework that would better recognize both the strength of Indigenous practices, and the impact (both positive and negative) of the development work we were doing. My intention was to consider where the critiques of international development could contribute to PO and how to include more local materials, resources, and cultural knowledge.

Margaret Kovach, an Indigenous scholar based in Saskatchewan, offers particularly significant advice to both Indigenous and non Indigenous scholars who are committed to Indigenous knowledges. Kovach’s writings on the importance of thinking critically about our own roles and responsibilities in the work we do, knowing the history of a place, and making sure that our work is done in relation to those we are working with prompted me to offer recommendations based on my personal growth and learning. I share these thoughts, not to be understood as final, but to spark dialogue among those involved in international education partnerships. I am certain there are past and current CTF co-tutors who are far more aware than I about practices that put the his tory, needs, and culture of the host country at their centre. However, it is likely that there are many volunteers who, like myself, have room to grow.

Prioritizing Reading: Because CTF co-tutors are con strained by time during the school year, rarely do we have an in-depth understanding of the historical and contemporary issues faced by the destination country. Without dismissing the reading that many co-tutors do in preparation, my suggestion is to simply take this aspect of planning seriously. It seems many CTF co-tutors, including myself, spend a lot of time fundraising, working on detailed lesson ideas, and reading tourist-based literature on the host country. Novels, historical pieces, and research-based articles about volunteer tourism and development work would all be useful in preparation, adding depth to our understanding. It is not realistic to expect co-tutors to read endlessly before heading overseas, nor is this the only step necessary for effective work. Instead this reading has the potential to move us forward and to develop a framework that includes multiple social and historical layers.

Prioritize Local Materials: Many volunteers feel that incorporating local resources into PO is very important, and I remember conversations about this at pre-departure training. My research shows that Sierra Leonean educators also place great value on local knowledge. Until my fieldwork, I did not realize just how limited I was in this capacity. I remember my team suggesting teachers use bottle caps for math counters since we were finding them all over the streets of Freetown. These suggestions were well-intentioned but we were told there were no soft drinks available in rural villages, the communities where the workshop participants taught. We also suggested using natural products such as seeds. An interviewee explained that hungry students might eat the counters. So even in instances where we thought we were incorporating local materials that would work, we were not. Taking the time to facilitate discussion about local materials and knowledge in our PO workshops and with our co-tutors is crucial to developing a locally relevant program.

Valuing Cultural Knowledge: knowledge has been an important part of my learning experience and has guided my recommendations. During the interviews, teachers specifically mentioned in corpo rating cultural knowledge. One Sierra Leonean teacher believes drumming, dancing, and local rhymes should be emphasized in PO and stated that children should not be separated from their culture. Another teacher thought PO should include many topics in relation to cultural knowledge, such as the history and migration of different ethnic groups in Sierra Leone. He stated that every district in Siena Leone has a story for its name and believed this topic would provide a strong starting point for discussion. Work in together, we can develop curriculum that includes this cultural knowledge.

Asking Deep Questions: From my experience, participants in Sierra Leone are often very excited to be a part of PO and meet Canadian teachers, and seem to enjoy the interactive experiences. As a Canadian co-tutor, it is easy to get lost in this excitement, with a great feeling that you are making a difference. This enthusiasm can drive the program forward but it is important to step back and ask questions.

For example, the following critical questions, adapted from the work of Linda Tuhiwai Smith and Shawn Wilson, could remind us about PO’s intentions and help us infuse local resources into the workshops whenever possible.

- For whom is this project relevant and how do I know? Who defined the terms of the workshops?

- What is my role in the co-tutor relationship and what are my responsibilities?

- How do I help build respectful relationships with all those involved in PO?

Our responses and the conversations that unfold could lead not only to improved understanding of international relationships and histories, but also to our challenging them.

Debriefing: An experience abroad does not necessarily mean that people have learned or progressed in their thinking. Instead, it can actually reinforce stereotypes about the host country, our role as volunteers, and/or poverty. This is why a debriefing component is critical upon our return home from PO. Not only is it important for volunteers to share stories, we also need a formal opportunity to think critically and confront our personal beliefs and actions. Asking deep questions and taking time to engage in critical dialogue helps us process our stories and opens our minds to other interpretations. At a recent ETFO debriefing session, we discussed the power of our messages upon our return home. We need to ensure that we are passing on a clear message to our students, colleagues, family, and friends that this is our interpretation of the experience, not the experience.