Literacy Links... Generations of Readers Ioaether

There is an old African proverb that has become universal in the world of education. This slogan has been adopted into the pedagogy of our profession and provides a moral basis for our workings. “It takes a whole village to raise a child,” is easily tossed about in dialogues and trains of thought, but to build it directly into the curriculum has proven to be the greatest challenge and perhaps the greatest triumph of my career thus far.

It began in my third year of teaching. The school — centred in a hardworking community, where English was often not the first language of choice in many households. The class — a grade 4 comprised of 20 students of varying abilities. The target — to instill a passion for literature. Passion is an extreme word, and like most extreme words, it carries a heavy weight that is difficult to uplift by the force of just one person, perhaps because it is so strongly rooted in the elements of knowledge, success and appreciation. As a single educator in a generalized grade 4 class of readers with mixed abilities, my target felt more like a loophole that led straight into a pipe dream.

Still, I grappled with my goal. Throughout my education, I had come to understand the value of communication. Communication is a basic necessity of life. Like food, words nourish the mind. Take away words and all students are left with are negative social behaviours to express their ideas. “Behaviour disturbance, in particular anti-social or conduct disorders, are associated with difficulties in reading.” (Rutter, Tizard and Whitmore, 1970) Snowballed over time, this could spark heightened aggression and perhaps even violence. Put into the context of the future, my target became charged with a whole new perspective.

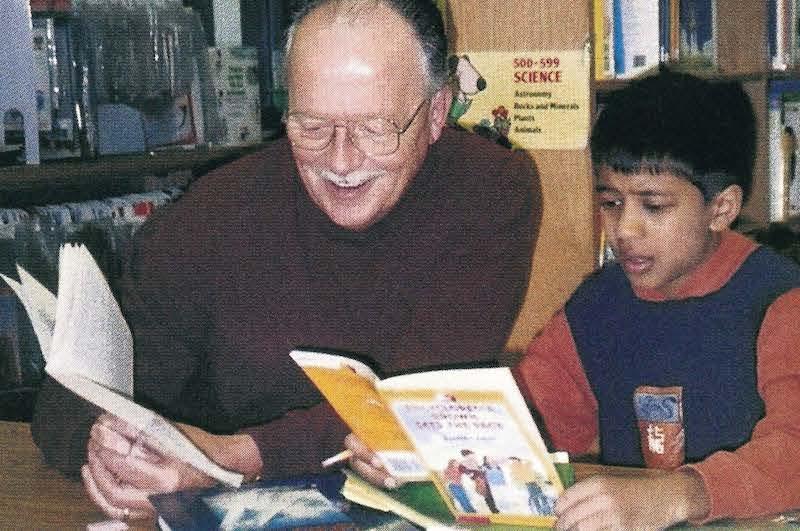

I knew what my students needed. They needed their own guide who could steer them through the individualized bumps and obstacles found in the terrain of literacy; someone who could help them read between the lines and appreciate the author’s intent; someone who had the time to sit down and have one- to-one discussions that approached and solved the reader’s individual queries. Time, patience and a love for books — that’s what the job called for. Finding a group of people who could fit this demanding description is how the individualized reading program “Literacy Links” came to be.

In a way, I was looking for surrogate grandparents who could impart a love of literacy in their own unique and nurturing way. What I got was so much more. In the summer of 2000 I approached various senior community centres with my idea and was welcomed with open arms.

As the school year approached, I was energized by the prospect of a group of children who would bring with them a whole new set of personalities and learning styles, that would expand my teaching repertoire. I went through the usual motions of getting my classroom ready for learning. But this year would be different from the others. To prepare for my upcoming journey through the Literacy Links program I had purchased a journal in which I would record the weekly events as they unfolded. Here are just a few of the many highlights.

Wednesday, September 27

Seventeen seniors meet my class of 20 students in the lunchroom of our school. My students are nervous about getting to know a new group of people that they are going to spend the year working with. Clinging tightly to book bags for security, they come prepared with readers specifically matched to their reading level and a duotang filled with generic worksheets. Their first task is to fill out a “Getting to know you” questionnaire. During this exercise, some of my students discovered that their reading buddies had served in World War II and lived through the Great Depression.

Wednesday, October 4

The reading begins. My students aren’t nervous this week. As they crack open the spines of their new novels, I circulate down the rows of lunchroom benches. Each worksheet comes with instructions. I clarify when needed and make sure that the sheets are being filled out correctly. The children write and discuss setting, characterization and vocabulary. Each chapter is chunked by end of chapter questions that the seniors formulate for the children and that I read after each session.

Wednesday, October 18

I overhear a conversation between a little girl in my class and her reading buddy. It isn’t dealing with the black and white details contained in the novel, but rather real-life experiences that relate to setting and paint a background full of colour and richness. The story is set in the back-drop of mid-west America during one of the bleakest periods of history, The Great Depression. This particular reading buddy lived in Oklahoma in the 1930s and described a natural disaster known as the Dust Bowl. “We had to wear hats with wide brims, kerchiefs over our faces ... we had to put Vaseline in our nostrils to prevent breathing in the dust ... the black blizzards destroyed everything.” Her words echoed the feelings of the story’s main character. This woman’s empathy gave the character a third dimension which brought her to life for the little girl.

Wednesday, October 25

The lunchroom is occupied, so we change our weekly venue to the library. One of our senior reading buddies — a retired journalist, freelances as a magician and offers to put together a magic show aimed at literacy. During the last ten minutes, he works his magic on a receptive audience, yearning to be entertained. He teaches them how to look words up in the dictionary, and how to use a thesaurus, with the tap of a wand and the inner workings of a black top hat. After the show, I ask my students what they had learned. Naively they reply, “Nothing. We just had fun!” Initially I was disappointed, but in retrospect I realized that the best classroom should be a stage where learning recedes into background and fun takes over the spotlight.

Wednesday, December 13

The day of the Literacy Links party The roads are layered in thick, persistent ice. The wind is fierce. As I watch the flag outside our school flailing frantically I am afraid that many seniors will not be able to come. My students look forward to the party; They have made napkin ring holders in the shape of poinsettias and rehearsed a French Canadian carol. I can tell by the straightness in their postures, and the expressions in their voices, that they feel important. I don’t have the heart to tell them their guests may not come. Luckily I didn’t have to. Every senior came, and not once did they complain about the weather. Instead, they just went on doing what they loved best — reading. Even though I never go into detail about the obstacles some seniors cross just to make it to our sessions, I know my students understand — an unspoken truth that draws our group closer together.

Wednesday, March 21

One of the reading buddies and a student engage in a discussion around the word “crackerjack.” It’s a word contained in the novel they are reading. They talk about the word and how it is used in the context of the book. The reading buddy, who is somewhat nautical, provides insight into the origin of the word. He explained that “crackerjack” was a term derived from the Vikings. It was used to describe tidbits of leftovers meats, biscuits that were mixed together in a stew-like fashion, for sailors aboard ships. As I watched the student, I could tell by the grin on his face that he was intrigued yet distanced from the conversation. Perhaps the origin of this word lay too far out of the realm of his own experiences. In order for it to make sense for him, the reading buddy shifted gears and talked about a subject with which every child is familiar — candy. He related crackerjack to the confectionery concoction of peanuts, popcorn and caramel, as tidbits of food put together. He told the boy that the next time he goes to the store to take a closer look at the packaging of this candy, for a clue to the origin of the word. Before the reading buddy could finish his sentence, the boy’s face was transformed by excitement. “I know!” he declared. “There’s a sailor on the front of the bag! ” As one fisher would say to another, the reading buddy had reeled the student in.

Wednesday, June 13

The first year of Literacy Links draws to a close. I can say without any hesitation that it has been a success. Most children have improved their reading scores by a whole letter grade. But more than just a development in academics, there is a development that cannot be quantified on paper. Perhaps it is because it lies in the children’s smiles when they learn important life lessons through the author’s unspoken words. Or perhaps it lies in the excitement of the students’ voices as they and their reading buddies embark on journeys where the only ticket for travel is imagination. Whatever the case may be, success, knowledge and appreciation are budding below the surfaces of written text. I can see it and I can hear it as I feel students’ shift from having to read to wanting to read.

The students prepare gifts for their reading buddies as tokens of their gratitude. The gifts are a perfect metaphor for learning - hand-painted ceramic garden pots each containing a packet of seeds. But more than the seeds of any flower, our seniors, through their wisdom and devotion, have planted seeds of passion. Over time, this will bloom into a love of literacy which will outlast and outshine even the fairest of roses. The future looks bright. Teachers and parents from other schools are interested in starting similar reading buddy programs in their communities. Over time, Literacy Links may add a novel twist to a textbook tale. And perhaps it will go something like this ... “Once upon a time there was a village who raised a child, and then along came a group of people who proved that it takes a generation to teach one.”

Seema Mehta teaches grade 4 at Lucy Maud Montgomery School, Scarborough.

Reference

Rutter, M. Tizard, J. and Whitmore, K. (1970b) Education, Health and Behaviour. Longmans, London.