When School Isn't...

It was when he was reviewing his school’s reading scores in September 2002 that the light went on for Wayne Copp, principal of Toronto’s Baycrest Public School.

“I was looking at our DRA (Developmental Reading Assessment) results for September through to June and instead what was glaring at me was June through to September, “ he explained. “After I did the math, I saw that our kids were, on average, losing six levels over the summer.”

At the time the school could, at best, hope to place five Grade 3 children in the board-run summer school program. Wayne Copp had bigger ideas. He wanted to run a literacy and computer summer camp for 75 of his students, about a third of the school population.

Not that it was easy. “We thought we were dead in the water at least three times,” he recalled with a wry smile. The first problem was finding the necessary funding. The second was how to guide this novel idea through the thicket of regulations and bylaws. And when seed money was found and the regulations met, the problem was staffing.

“I didn’t know if any teacher would be interested. I knew we had very limited funds. We won’t mention what we paid those teachers. If I had had a number of teachers say ‘Sorry, Wayne, I have other plans for the summer’ then it would have died right there.”

Given the tight budget there was only a small honorarium for teachers who took on the task of running the program that first year. In fact some thought it was a volunteer position and were pleasantly surprised to find out they were getting paid at all.

The result? Not one kid who attended camp lost ground in reading over the summer as measured by the DRA.

This year the Toronto District School Board will operate 24 to 27 summer camps across the city. Although there is a curriculum of sorts, a key to the camps’ success is the level of autonomy each has in deciding the methods it will use and the activities it will provide for its kids. Teachers are not only free but are encouraged to improvise, to use their own creativity and ideas in teaching the children. The result is a group of summer camps with common aims but widely differing approaches.

Mary Plevak-Mohamed taught the JK to Grade 1 class last summer. What struck her most was how well the teachers worked together. “It was an excellent group. Having a team like that makes all the difference. All of us were committed to developing our kids’ literacy skills and to the children themselves.”

The children made and flew kites, explored bubbles and wind, and had plenty of time for songs, poems, rhymes and dance. A trip to the local bagel shop let them form their own bagel and then watch as it was cooked before their eyes. Needless to say, the little ones were thrilled.

With so many neat things to do, it is not surprising that out of a class of 25, attendance usually ran to about 24 students, dipping rarely to 21. That in itself speaks to the success of the camp.

Each classroom had three high school students who acted as tutors and education assistants. Mary was high in her praise of her students. One of them had a talent in music and would lead the children in daily sing-songs and dance, while another was particularly adept at computers and acted as a resource for the camp as a whole. All took the initiative as opportunities presented themselves.

Most teachers would love to have even one assistant in their classroom. Having three meant that each child received much more intensive and individualized attention. Moreover, it may prove to be a valuable recruitment tool for students who had not previously considered a career in teaching.

When asked if she would recommend teaching at the summer camp to a fellow teacher Mary laughs: “Well, I enjoyed it a lot but it really does require commitment and energy. But I felt good at the end of it all, knowing that we had made a difference, that it was such a positive experience for the kids.”

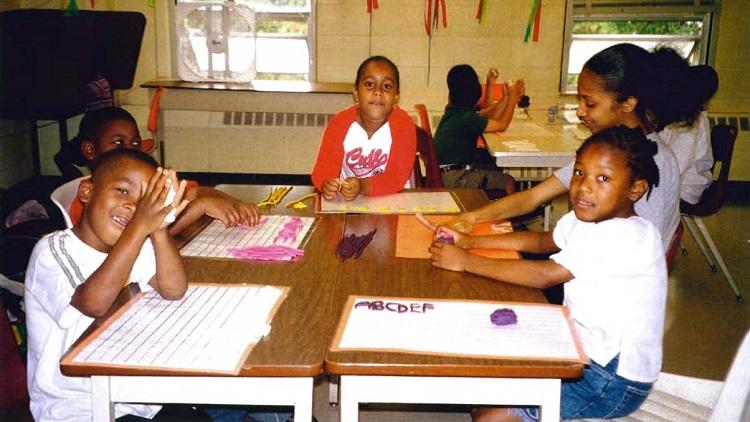

And what of the children themselves? Key to the success of the summer camps is that they are indeed summer camps and not summer schools. As someone who had to go to summer school for Grade 11 algebra, I can well understand why most kids would be reluctant to spend any of their summer vacation back in a school building. Unlike summer school, summer camp is designed to be fun. One third of the time is spent on academics, another third is spent on computers, and another third is devoted to the arts.

Of course, the ultimate assessment is the one that comes from the children themselves. During a round table discussion with some 11 year-old graduates, one child volunteered, “It felt kind of weird. On my summer break I usually go to the United States, to Los Angeles. I was mad because I had to go but it turned out to be a lot of fun.”

“I really didn’t want to go because I didn’t want to do any work on my summer vacation but it wasn’t work,” another piped up. “Well, half of it was and half of it wasn’t. There was a lot of gym and computers. We got to go on a lot of trips, like to the doughnut place (the Krispy Kreme factory).” Surprisingly one child liked working in her notebook best. “We did reading, crossword puzzles and science about polar bears.”

At one point the discussion became so animated that the children were talking over each other as they recalled the great time they had at camp. Not too surprisingly snack time and a chance to play soccer in the yard or basketball in the high school gym were big plusses as well.

Wayne Copp wanted it to be a summer camp rather than a summer school. He wanted it to be fun for kids. When I tried to suggest that the summer camp was sort of like school, I was immediately corrected by the kids. “It was way better than school!”

Bruce Stodart teaches at BaycrestPublic School.