Women, Work and COVID-19: The Road to Recovery Begins and Ends With The Care Economy

Women have been frontlined and sidelined by the pandemic in their roles as primary caregivers and care workers in the public and private sectors and as the majority of workers in sectors hardest hit by ongoing economic shutdowns. Women were certainly not all in the same place going into the crisis, and their lives since February 2020 have followed different paths. Groups and communities least able to shoulder the social and economic fallout of COVID-19 have borne the greatest risks and damaging impacts.

The third wave of the coronavirus is now rolling over Ontario’s major population centres. Large numbers of low-wage female workers have once again been laid off, while others scramble to stickhandle virtual schooling and care for ill family members. Essential workers on the frontlines in care and education are working under acute stress; a year into the pandemic, many are still without access to basic protections such as paid sick leave, effective protective equipment or safe working conditions.

Federal emergency benefits have played a critical role for women, offsetting a devastating collapse in employment earnings, especially for the most marginalized, but provincial investments in women’s employment have largely been an afterthought, exposing the systematic undervaluing of women’s paid and unpaid work.

The federal budget holds out the promise of transformational change in the provision of child care across the country – a critical support to women and families everywhere – but the fight over the future of the care economy is far from over. Getting the provinces on board won’t be easy politically; many, such as Ontario, are already bent on a course of austerity and further privatization. The stakes for women couldn’t be higher.

Women, Work and COVID-19

A year’s worth of economic data shows clearly that women have shouldered the largest economic losses throughout the pandemic.

Female-majority sectors were hit hard and fast. Across the country, by the end of April, 1.5 million women had lost their jobs and another 1.0 million were working less than half of their regular hours. This compares to fewer than 250,000 jobs lost among women in the three previous recessions combined.

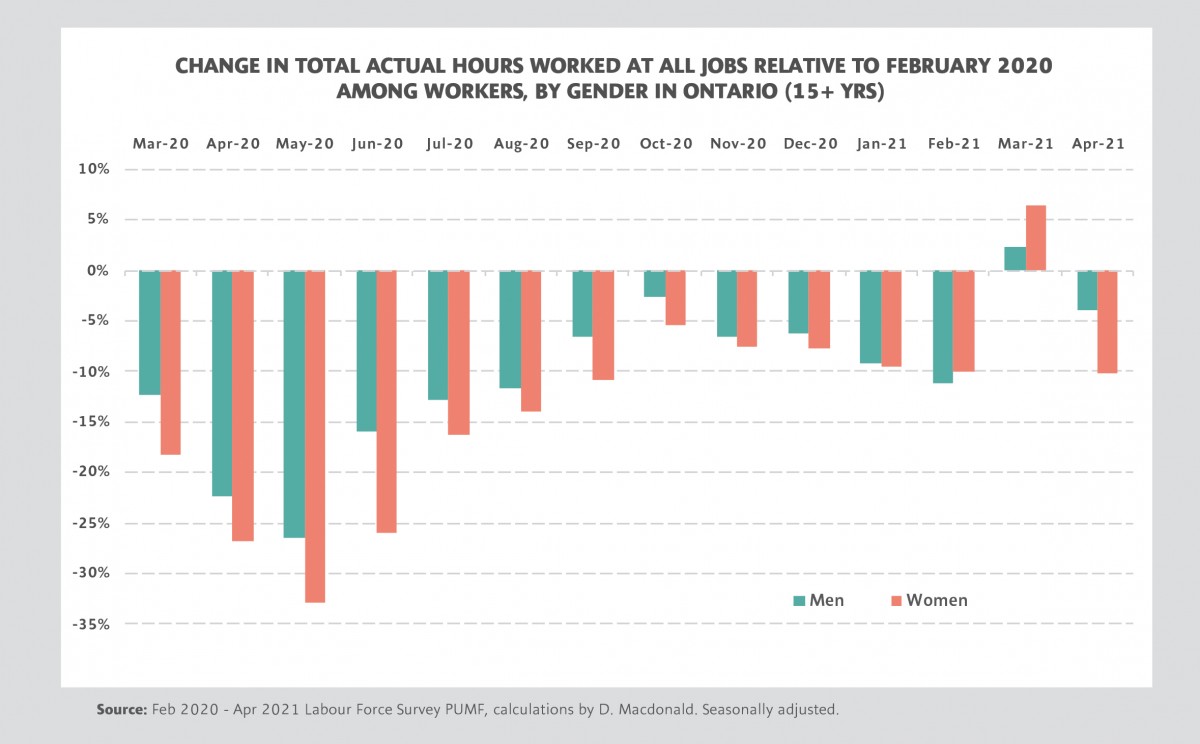

The largest initial employment losses were predictably reported in the provinces most impacted by high rates of infection during the first wave of the pandemic, notably Quebec and Ontario. By May 2020, Ontario women were working 33 percent fewer hours than in February – higher than both the national average for women (at 29 percent fewer hours) and the average for Ontario men (at 27 percent fewer hours).

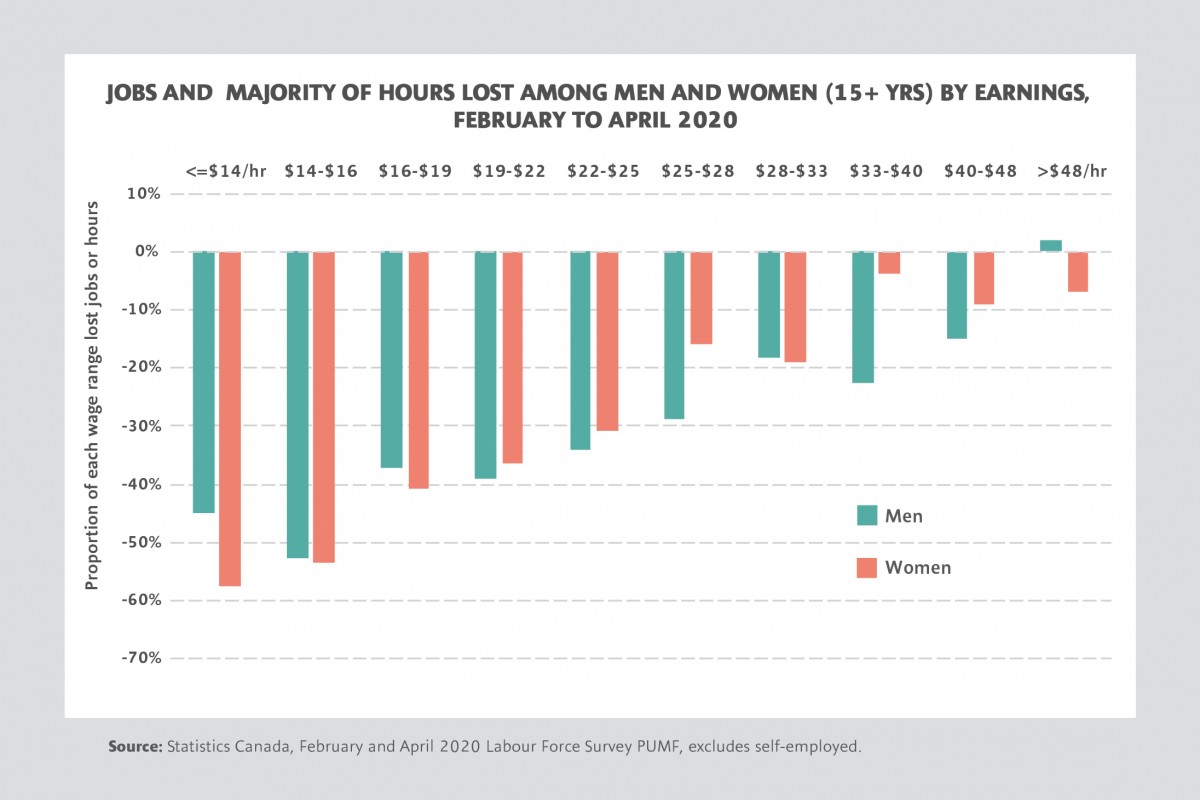

The breakdown by hourly wage was perhaps the most shocking of all. Over half of Ontarians earning $17 an hour or less (52 percent) were laid off or lost the majority of their hours between February and May. This compares to a loss of only 3 percent of jobs or hours cut among the richest 25 percent of workers making more than $35 an hour.

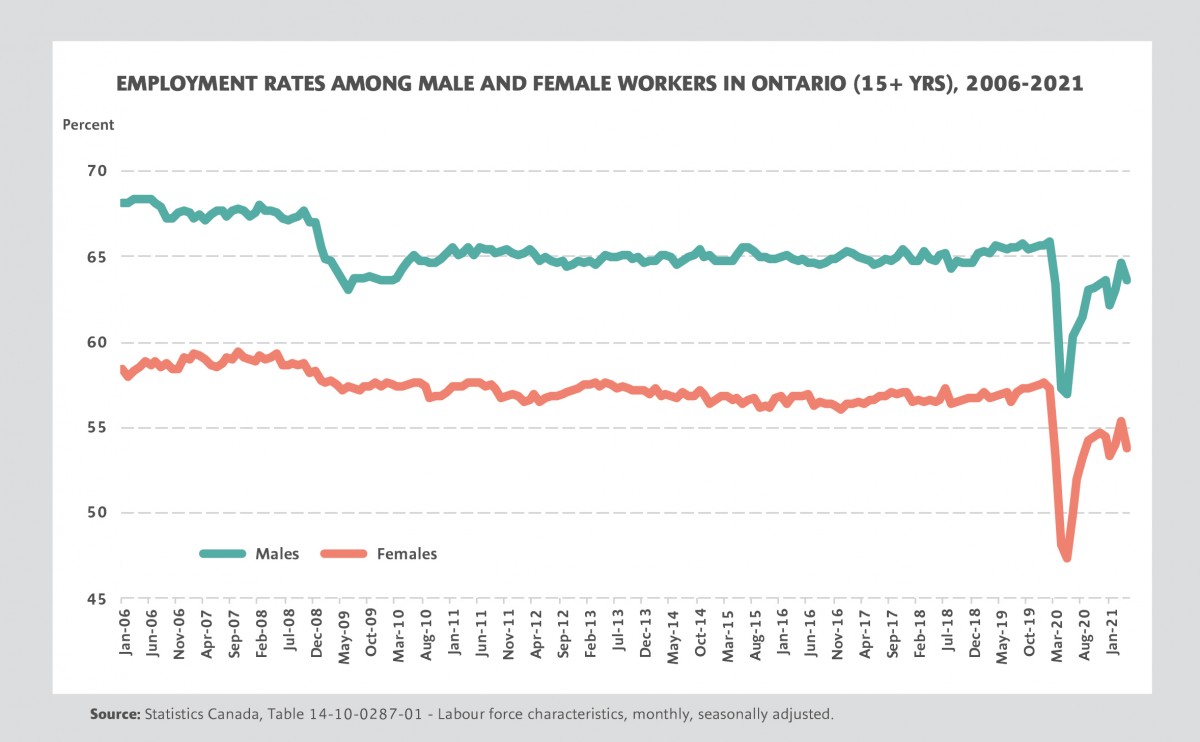

By year end, female workers in Ontario were working roughly 8 percent fewer hours, in the aggregate, than before the pandemic, while the December 2020 employment rate (54.5 percent) was 2.8 percentage points below the rate posted in February 2020, the same level of women’s employment as in the late 1990s. It fell again sharply in January to 53.3 percent, rebounding in February and March, then dropping again in April as the second and third waves of community infection precipitated new rounds of economic closures.

The Recovery is Proving to Be as Unequal as the Downturn

The recovery is proving to be as unequal as the downturn. Some groups of workers recouped their employment losses quite quickly, but those working in low-wage, front-facing sectors such as accommodation and food services and community services are reeling from successive economic blows and the direct impacts of community spread.

And again, women are bearing the largest share of these economic losses – more specifically, young women, women with disabilities, racialized women, Indigenous women and others facing employment barriers – all caught on the wrong side of Ontario’s halting recovery.

This figure shows Ontario’s K-shaped recovery, a pattern evident among both women and men. The level of female employment in vulnerable industries in December was 12 percent below February levels, down 10 percentage points from August, a gap that widened in January to 25 percent, snapped back in February and March, then fell in April. The upshot: low-wage workers have been treading water for months.

Large numbers of Black, racialized and Indigenous women work in these hard-hit sectors and occupations. In July 2020, the month that Statistics Canada began reporting on the experiences of racialized groups, there was almost a 7 percent difference in the national employment rate between racialized and non-racialized women (57.7 percent vs. 64.4 percent) and more than an eight percentage point difference in their unemployment rate (17.4 percent vs. 9.2 percent). These gaps narrowed somewhat between July and April 2021, but they are still significant.

This has been the most troubling trend of the economic downturn. Low-wage workers and their families are on an economic roller coaster. At the same time high-income earners have prospered, not only continuing on with their jobs but also realizing the gains associated with the run-up in housing values, pension plans and investment holdings and the savings associated with working from home and deferred travel and entertainment.

The Crisis in Care is Upending Women’s Lives – Especially Among Lone Parents

The other key part of this crisis for women’s economic security is what has been happening on the home front. With little help forthcoming, women have stepped up to shoulder the huge increase in unpaid labour that has accompanied the pandemic.

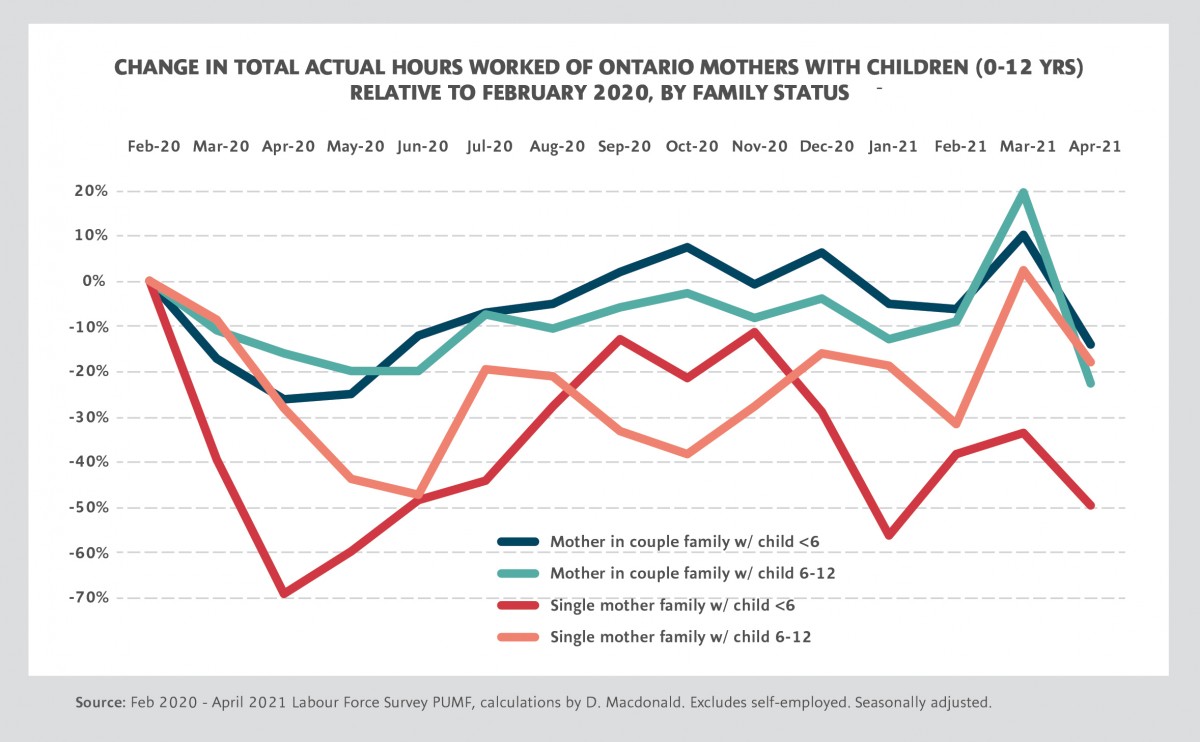

Employment gains since April 2020 have lagged among mothers with kids under 12, pointing to the impact of school closures, uncertain access to child care and unequal division of labour in the home, stresses that are particularly acute for those actually working in care and education sectors.

On this score, lone parents have experienced greater loss of employment and hours than parents in couple families and they are recovering more slowly. Indeed, since October, single-parent mothers with children under 6 have lost considerable ground. Looking at Ontario in April 2021, they were working 49 percent fewer hours than in February 2020, while single mothers with school-aged children (6-12 years) were working 18 percent fewer hours.

These figures don’t include the proportion of women who have dropped out of the labour market altogether, putting aside their own financial security to stickhandle the ongoing demands of the pandemic including the ongoing stress and uncertainty of schooling.

As of April 2021, there were almost 95,000 more Ontario women aged 15 and older who were “not in the labour force” than in February 2020 (and 215,000 fewer women across the country). Women aged 35-39 are exiting the labour force “in droves,” according to research from RBC Economics. After improving in February and March, the number of women outside of the labour market increased again in April.

Investments in Care Are Hit and Miss, Mostly Miss

When the pandemic hit and governments ordered the economy-wide shutdown to contain the virus, the federal government stepped in to directly assist families, notably with the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). Instead of private households carrying the burden of unemployment, the federal government took this on.

However, on the critical issue of care – and I would include education here – governments have been reluctant to act, expecting households and particularly women to shoulder the huge increase in unpaid labour that we have seen these past few months and expecting school authorities and educational workers to figure it out with scant support in terms of funding or guidance.

Provincial governments have abdicated responsibility, committing woefully inadequate sums of money (the lion’s share comes from the federal government) to services such as child care and education to ensure learning success and safety. Provincial funding on child care, for instance, represented just under half (49 percent) of total monies spent on pandemic-related support for child care between March and December 2020.

Among the provinces, British Columbia made the largest investment in its child care services (at $282 million) on top of its share of available federal funding, funding that helped to offset the financial precarity experienced across the sector as a result of declining enrollment and rising costs.

The Saskatchewan government, however, had yet to fully allocate the federal funds it received for child care by the end of 2020, while Alberta and Manitoba have contributed very little of their own resources to bolster child care in their jurisdictions despite women’s lagging employment recovery and the considerable loss of capacity in the child care system as a result of the pandemic.

Similarly, provinces have not stepped forward with robust reopening plans for schools. In Ontario, the 72 boards of education added the equivalent of only 1.5 staff per school to deal with all the pressures from school closures, online learning, preventive health measures, additional mental health challenges and growing learning gaps. And of the funds put up for these efforts, 46 percent came from board reserves, 18 percent from the federal government and only about one-third from the provincial government itself.

The near global refusal to address the untenable tension between women’s paid and unpaid work through proactive and meaningful investments in care and education, targeting the most marginalized, serves only to strengthen the employment barriers women are now facing.

Who is Paying The Price of Our Failure to Act?

Our children and young people are paying the price. This is especially true for those who have already fallen behind and don’t have access to needed supports for their healthy development, a situation that is destined to worsen as the scale of student disengagement over the past year becomes clear. Teachers are already sounding the alarm about students who have disappeared from their class rolls.

Our teachers are paying the price. They are overwhelmed, stressed and exhausted. Teaching has changed fundamentally, demands on teacher’s time has increased exponentially and yet there’s been no time to adjust. A third of all teachers are considering changing professions or retiring according to a CBC poll fielded last fall.

Mothers are paying the price. A large majority of women (71 percent) are already reporting being more anxious, depressed, isolated, overworked or ill because of the significant increase in unpaid labour, including child care and homeschooling, that has occurred over the past year.

Stress and anxiety are even higher among mothers living in poverty or from marginalized communities, those most impacted by the economic crisis – waiting for the next shoe to drop as the recovery stops and starts, rental evictions proceed, and infections continue to circulate.

What’s Needed: An Intersectional Feminist Recovery Plan

What’s needed is a clear analysis and plan of action that centres care and well-being. This includes investments in child care, a fundamental support to children and families as well as the larger economic recovery, and in education and other female-dominated sectors such as long-term care and community services. These investments will not only enhance quality of life, but strengthen our society over the long term, tackling the sources of systemic discrimination and better positioning us to effectively respond to crises and excel in new ways.

On this score, historic investments in child care of $30 billion over five years, announced in the federal 2021 budget but dependent on negotiations with the provinces and territories, could be a game changer for women and their families across the country. Combined with other strategic investments, it represents an historic opportunity to set women’s economic recovery on a strong course, boosting participation rates and household incomes, enhancing the quality of care economy jobs, closing damaging gender pay gaps and generating inclusive economic growth.

The proposed multi-year plan will help stabilize the current child care system and support the expansion of high quality, non-profit, affordable child care. The government has set a target of reducing average fees by 50 percent in all provinces and territories outside of Quebec by the end of 2022 and set aside additional funds to support training and enhanced accessibility for children with disabilities.

Budget 2021 also promises investments of $2.5 billion in skills and training that includes a commitment to create 500,000 training and work opportunities over the next five years, targeting support to those from underrepresented groups, including women, persons with disabilities and Indigenous people, as well as stronger protections for gig workers and a minimum wage of $15/hour for workers in federally-regulated industries.

These actions all strengthen community infrastructure and are key to enabling women’s active participation in the economic and social life. The question at this juncture, months away from a potential federal election, is will the promise of this budget be realized? Will investments improve the working conditions and abysmally low wages of care workers? Advocates know that there is still much hard work ahead.

“The virus punishes half-heartedness,” German chancellor Angela Merkel has noted. Yet half-hearted measures are exactly what we’ve seen from governments across the country.

There is an opportunity for a fundamental reset at hand. Teachers are already stepping forward, pushing back against dominant narratives that there is nothing to be done, calling out the hypocrisy of government responses and extending mutual aid and support to those most in need.

But they can’t do it alone. It is long past time for all of us – and especially our governments – to treat the pandemic like the emergency it is and take the action needed to build back better.

Katherine Scott is Senior Economist, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.