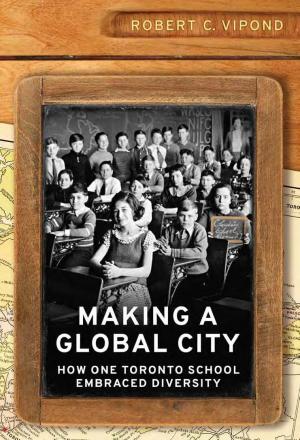

Making a Global Village: How One Toronto School Embraced Diversity

This history of Clinton School in inner-city Toronto is well timed to inform current discussions about immigration, multiculturalism and citizenship. It also serves as a counterpoint to the anti-immigrant narratives underlying recent political events such as the rise of Donald Trump, Brexit, European nations closing their doors to refugees and the political rhetoric regarding Canadian values during the last federal election. Educators will find the book a rewarding affirmation of the impact they can have on integrating immigrant and refugee students and shaping their future role as citizens.

The book chronicles how one school, in the context of evolving provincial and school board policies, responded to different waves of immigrant students. In contrast to most Toronto schools during the period covered, Clinton’s students were predominately new Canadians, which makes the school an ideal focus for a local history of immigration policies and social attitudes.

The book came about because school principal Wendy Hughes, a former ETFO activist, asked parent Robert Vipond, a political science professor, if he was interested in history. He was initially intrigued but Hughes reeled him in when she told him the school owned a complete set of student registration cards between 1920 and 1990 in addition to a well-organized archive that had been assembled in 1988 at the time of the school’s centenary. He also had access to Clinton alumnae, many of whom became Toronto notables, who provided rich anecdotal material.

In his telling of the Clinton story, Vipond matches the student demographics with those of the city and takes us through the decades by deftly situating the school in the broader social and political context. He also draws on academic scholarship to develop the discussion of issues related to immigration and citizenship, which adds another contextual layer.

Vipond organizes his telling of the Clinton story by dividing it into three chronological sections based on student demographics: Jewish Clinton (1920-1952), European Clinton (1950-1975) and Global Clinton (1975- 1990). Through each section we learn how Clinton served, at the micro-level, as an example of how Canada has evolved in its approach to immigration and how schools contributed to this evolution.

Jewish Clinton

During the Jewish Clinton period, the percentage of students who were Jewish ranged between 40 and 70 per cent. The book situates Jewish Clinton in the context of the anti- Semitism still present in post-World War I Toronto. Vipond cites a 1924 Toronto Telegram editorial that said of the Jews: “These people have no national tradition…They are not the material out of which to shape a people holding a national spirit…” Clinton was not immune to this prejudice and former students confirmed they had experienced anti-Semitism growing up.

The dominant Christian religions shaped provincial education policy. Vipond points to the Grey Book, the 1937 provincial education guideline, which stated: “The schools of Ontario exist for the purpose of preparing children to live in a democratic society which bases its life upon the Christian ideal.” The province did not replace the Grey Book until 1974.

How did Clinton respond to its Jewish students? Former students reported that individual teachers played an important role in making them feel comfortable at school, although there were exceptions. Clinton was one of the first Toronto schools to have a kindergarten program, which served to assist young immigrant children and their families adapt to their new home. Its extracurricular activities in particular served to cultivate cross-cultural interaction among students.

Jewish students at Clinton, like all Ontario students, were subject to daily readings of the Lord’s Prayer and the Bible. Some former students reported they found the religious exercises offensive, but more often Jewish alumnae recounted how their families were relatively indifferent and focused on Jewish education at home. Their families felt the religious exercises were a small price to pay to join the mainstream society.

The issue of religious education reached a crisis, however, in 1944 when the George Drew government invoked a regulation requiring all students in grades 1 through 8 to receive religious instruction for two half-hour periods a week. Clinton and two other neighbouring schools with predominantly Jewish students responded with civil disobedience. They either watered down the curriculum or noted the subject on their timetable and then ignored it. Their reaction was based on an appeal from the Canadian Jewish Congress, teachers’ relationships with Jewish parents through the home and school association and the schools’ desire to support their students. Vipond concludes: “Clinton was not part of some Anglo-Ontarian assimilationist juggernaut but an institution that worked together with parents to find what worked for its community of students and parents.”

The historical significance of this episode is that Clinton used the issue as an opportunity to bridge religious differences and foster a stronger community. It’s a lesson that Vipond suggests could have benefited those involved in the recent religious symbols debate in Quebec or the controversy provoked by the Harper government’s attempt to prevent Muslim women from wearing a niqab at citizenship ceremonies.

European Clinton

In the 1950s, the Clinton student population became predominately Italian and Portuguese in ethnic origin. For European Clinton, the dominant focus became the need to respond to language rather than religious issues.

Without any direction or assistance from the education ministry or Toronto Board of Education (TBE), Clinton created its own English as a second language (ESL) programs. Its first ESL class opened its doors in 1951. The school had to find its way through experimentation that included assigning all ESL students to one class, holding students back for a second year of kindergarten, and ultimately a more integrated approach that had students spend part of the day in intensive language instruction and return to their regular classroom for the balance of the day.

Drawing on academic literature, Vipond stresses that the board’s goals for ESL were “to assimilate immigrants, improve their educational standing, and socialize all children to the norms of the Anglo-Saxon elite.” According to former students, this assimilation approach was evident to a certain extent. They remember teachers reprimanding them for speaking Italian, anglicizing their names and calling their parents to encourage them to speak English at home.

By the mid-1960s, both the province and school board had woken up to the importance of immigrant education. The earlier assimilationist theories of ESL began to give way to goals related to individual student needs. In 1965, the TBE released a research report entitled Immigrants and Their Education, which addressed not what immigrant students needed to do to adapt to Canadian life but what the school system needed to do to support them.

Clinton also discovered the importance of having diversity among staff. Office staff who spoke Italian or Portuguese played an important bridging role as did educational assistants in kindergarten. Clinton alumnae talk about their cultural horizons being expanded by a Japanese-Canadian teacher who arrived in 1966 and how a black teacher became a role model and mentor.

Global Clinton

Language instruction heightened as a political issue during the Global Clinton period when the school’s demographics evolved to include students from Latin American and East Asian immigrant families. Between 1975 and 1985, the diversity of schools like Clinton provoked a debate about multicultural programing. The TBE established a multiculturalism working group whose final report in 1976 called for schools to provide immigrant children “with a means of recognizing their own cultural and linguistic heritage as a matter of routine experience.”

A number of schools set up heritage language classes offered as extracurricular programs by instructors from the various cultural communities. Clinton offered after-school programs in Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Greek. At the board level, support increased for extending the school day by 150 minutes a week to offer the courses within the instructional day, a proposal the Toronto Teachers’ Federation opposed.

Heritage languages were introduced to the instructional day if supported by a school-based referendum. Clinton, based on advice from a school sub-committee, ultimately rejected the concept. Parents were concerned about the impact of a longer school day for their children and the reduced opportunities for extra-curricular activities. They were also worried about the quality of the concurrent program for students not enrolled in heritage language classes.

In spite of significant pressure from the TBE, Clinton rejected the option. Vipond concludes that Clinton parents didn’t reject multiculturalism, but believed the school, especially through extracurricular activities, fostered cross-cultural understanding and worked effectively to integrate immigrant students. Vipond sees this moderate multicultural approach as a useful and defensible way of thinking about multicultural citizenship.

Public Education’s Contribution to Citizenship Building

Vipond looks back on Clinton’s history as a story of how one school sought to find “the right balance…between acculturation and adaption” and how through the process “it constructed multicultural citizenship.” Whether the school was responding to top-down policies or trailblazing its own approach, the underlying themes were the school’s understanding of its students and school community and the desire to help them succeed academically and as citizens.

Much of what Clinton staff and school community learned resonates with the equity work that ETFO promotes through its professional learning and resources – work grounded in reflecting classroom diversity and meeting individual student needs.

Vivian McCaffrey is an executive staff member at ETFO.