EQAO Standardized Testing is the Barrier

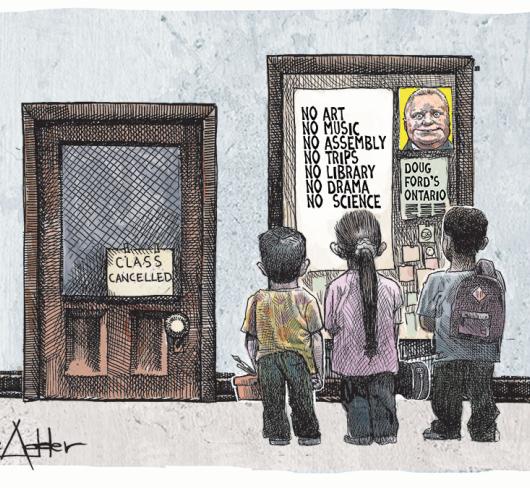

In spring 2020, the Ford government cancelled EQAO at the last minute in response to a shift to remote learning that was a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In spring 2021, the government announced that the EQAO test would resume as an online adaptive program, much to the dismay of parents, educators and education experts, all of whom have been arguing for many years that EQAO testing does not serve the primary purpose of assessment, which is to improve student learning. Furthermore, the online adaptive program that has been most recently introduced is particularly harmful as it streams students as they are working through the test. With public education in desperate need of investment to ensure that schools are safe and healthy learning environments and remain open to in-person learning, many have questioned why the Ford government has chosen this moment to instead funnel investment into a flawed testing model for students. In their public statements, the Ford government has acknowledged the uncertainty of the public health landscape and committed to a renewed focus on student mental health and well-being. In practice, however, they have initiated a new digital version of EQAO assessment that will only add stress to grades 3 and 6 students and siphon funding away from other much-needed investments.

What exactly are we testing with EQAO? Privilege? Disproportionality? Or are we testing students against each other on their ability to display colonial notions of grit and perseverance? What will we be measuring? As Ardavan Eizadirad (2019) more tactically asks in Decolonizing Education Assessment: “Who does the current enactment of curriculum and EQAO standardized testing benefit and who does it oppress, and more specifically in what ways and at what costs?” It’s time to end EQAO testing and to recognize that its continued use is antithetical to authentic student achievement and student health and well-being.

EQAO testing was built on ideologies that suggested that sameness equated to accountability. The concept of testing students’ knowledge stems from a belief that for students to be competitive against other industrialized countries, there needed to be a way to ensure that students were all being taught the same thing and were, in essence, complicit in being asked to represent their thinking in a mode that was monolithic in its approach and hegemonic in its objective. Regardless of its initial intent, EQAO testing has served to widen inequalities between students, schools and communities, as the data relayed to the public promotes an agenda of social stratification.

The institutional appetite for quantitative information has led to the overemphasis on setting benchmarks and constructing initiatives that do very little to affirm student identity and recognize the depth and breadth of immense knowledge that students possess. The students I work with every day tell me through their voices and their work what they need and not once have I heard students advocate for more testing. They want to feel safe in schools again; they want to feel that their ideas and experiences are reflected through instruction. Students, regardless of socioeconomic status, want to know that the elected officials who pledge to advocate for their health and well-being will commit to removing barriers that are a direct threat to their joy in learning.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the disproportionate impacts on those already marginalized by the system. It has shown us the dire consequences when governments ignore and reject the benefits of rethinking systems that are oppressive and, instead, perpetuate social hierarchies. If we are working towards justice and equity, we need to be aware that testing students, especially under these circumstances, will produce results that will increase societal barriers and characterize students as a product of their conditions rather than challenging systems that created these barriers in the first place.

The last two years have been anything but standard. How can we say to students that we care about their health and wellbeing and then turn around and gear up for test preparation when we know there has been very little that resembles an environment that is conducive for safe learning? Providing students opportunities to learn without the anxiety of being judged and ranked must be the educational endgame. Adding stress to students who are already mentally and physically stretched and spending resources that are needed for student supports and classroom health and safety on testing reflects a government that does not have its priorities straight.

Fear, anxiety, frustration and intergenerational mistrust are feelings on full display during EQAO testing. Students need to look forward to sharing their ideas with each other without the fear that their knowledge is being tested against their peers and being published to face ridicule by society. Honouring students is a process that starts the moment they enter the learning space each day. Honouring students goes beyond providing activities which are “feel-good” and easily recognisable tasks that only serve to capture the emotions of the moment.

Authentically honouring students requires self-interrogation of our roles in maintaining colonial structures. This process is uncomfortable but must be embraced if we are really committed to providing a rich experience for students and building stronger relationships with the communities we work with.

We know that students, regardless of their identity, enter into the learning space with a wealth of knowledge that has been shaped by their interactions with the world. These interactions are completely ignored through EQAO testing. What ends up being assessed are students’ memorization skills on content that is compounded over the course of a given year. I am concerned about the messaging that we are sending if we continue the practise of standardized testing based on a set of rules that are no longer relevant for the 21st century learner. Given the extensive impact of disrupted learning, we must set initiatives and benchmarks that allow students to rediscover the excitement in learning meaningful topics that build critical thinking skills by analyzing the problems in a constantly changing world. We must ensure that we are working with the support of a government that understands why this approach is both necessary and essential.

Differentiated instruction and assessment has become more important during the pandemic. While learning has been disrupted, students, educators and parents have done their part to demonstrate creativity and flexibility in the face of constant adversity. We know that students absorb ideas differently; we know that providing multiple points of entry not only engages the learner but builds confidence in understanding the material. We also know that when students are given authentic and meaningful inquiry opportunities to explore topics of interest, they are more interested and engaged in the process of learning. EQAO is in direct opposition to the creativity that students are encouraged to show. That same creativity has been taken away as a direct result of the learning conditions brought on by the pandemic learning model.

If we want to focus on math (more specifically data management) then let’s consider that test scores and school rankings are highly likely to maintain stereotypes, biases and discrimination, that I, like many others, are fighting to dismantle. The “numbers game” has allowed stereotypes to be operationalized in implicit and explicit ways to create division among schools and communities. The disrespect we will show to students and communities by requiring them to take part in high stakes testing will continue to demonstrate that our system values the output of student achievement rather than the process. It is the same value system that has seen racialized students disproportionately streamed into lower academic courses.

Accountability starts with leadership and the ability to diagnose inefficient and discriminatory macro-policies and procedures that profoundly impact the collective experiences of people. Accountability in the education system should not come at the expense of students and educators. Collaboration, student-led inquiry and culturally relevant instructional practices are the standards of teaching at the moment. As students return to the classroom, this method will need to be even more emphasized as we strive to enhance the academic, social and emotional well-being of our students. This is what accountability is and should be.

Picking up where we left off prior to the pandemic is the most destructive mindset that we can have moving forward. Reconditioning our educational system to view equity as a lifestyle and not an initiative is an exhausting endeavour. Further complicating the matter is the absence of critical consciousness from appointed officials to make informed decisions about student achievement and improved learning opportunities in the face of the pandemic. A prerequisite for societal change requires an understanding from its members that status quo policies that maintain cultures of superiority and inequality must be abolished. The belief that our system will benefit from assigning a numerical level to students in the midst of severe disruption must be challenged by all who claim to serve in the best interest of our students.

We have to get out of the persistent pattern where we offer apologies to students and communities for systems that have rationalized oppression throughout generations. Now is not the time to rethink or engage in “kick the can down the road” dialogue about the validity of EQAO testing. It’s time to rid the system of assessment measures that dehumanize the learning experience of students. Too much time has been spent on analyzing the numerical data on the performance of students on standardized tests. The pandemic should not be viewed as the conversation starter towards ending the role that standardized testing will play; it should serve as the catalyst to validate the removal of it. What is to be gained with the results? What is to be lost if we move forward with the status-quo?

When I work with my grade 7/8 students each day, I am constantly challenging them to think about how implicit and explicit messages are operationalized to impact their experiences in the classroom and in larger societal interactions. Rehumanizing math and language experiences through cultural contexts and personal interests is how we remain accountable. Maintaining the norms of accountability through EQAO testing will do nothing to re-establish a culture of learning. The message that will be sent to students and communities moving forward will expedite the decline of student confidence and trust within the system as students are left wondering if they will ever “measure up” to subjective standards that are pre-determined by those who are not on the front lines. What we don’t want to do is look back at this period in time and ask ourselves why we found it necessary to continue enforcing a system that is more concerned with classifying students and schools.

Students and communities rely on their governments to take proactive steps to think beyond the initial sting of any given crisis. This government has clearly refused to do that and it is parents, educators and students who will be waiting on election day to hold them accountable. We need to move forward with a vision that rids the system of a tool that has colonial roots, that creates more division and will never legitimize the authentic learning journey of our students.

Sean Lewis is a member of Elementary Teachers of Toronto.