The Long Road to Safety at School

November 2003 seems like a long time ago, and I could never have predicted then where I would be now, or what has been accomplished.

Having a son who is gay has been one of my greatest joys, yet one of my greatest sorrows – sorrow because I know that because of my son's sexual orientation, there are people who hate him and there are places where he will never be safe. My journey began on the November day that my son Gabriel was suspended for fighting in high school. From that day forward I could no longer ignore that my son was not safe at school, and never really had been.

Gabe's journey began when he was a little boy of eight in public school. By the time he was in grade 12, he had been living with homophobia every day since he started high school. The day he had enough and physically fought back was the day I stopped hoping he would be okay in school.

I pictured myself as a teacher who tried to understand the circumstances of all of the children in my class. I knew that, statistically, one in three girls will be sexually abused, that one in six children live in poverty, and I always tried to reach out to those children who were having the most difficulty. But at the same time, I missed what was happening to my own son. At age eight he was already being targeted by some in his school and later was harassed every single day of his high school career. When he finally told me what was happening to him, it took another four years before the school system acknowledged it. He came forward knowing he would never benefit. But how could I have missed what he was going through?

Statistics from the First National Climate Survey on Homophobia in Canadian Schools, Phase I –January 2009 compiled by EGALE Canada, bear witness to the reality of being gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, two-spirited, questioning, and queer students (LGBTQ) or being perceived as such in Canadian high schools. Three-quarters of all participating students reported hearing expressions such as “that’s so gay” every day in school. Half heard remarks like “faggot,” “queer,” “lezbo,” and ‘‘dyke” daily.

Six out of ten LGBTQ students reported being verbally harassed about their sexual orientation. Three-quarters of LGBTQ students and 95 percent of transgender students felt unsafe at school, compared with one-fifth of straight students.

Over half of LGBTQ students did not feel accepted at school, and almost half felt they could not be themselves, compared with one-fifth of straight students.

Most telling are the comments from students who responded to the survey, of which these two are typical:

" The teachers know it's going on, but they rarely pipe up and protect me or others. I guess they figure it's a lost cause. It takes a lot of energy to defend yourself all the time."

" I am not out because if I was I would probably get beat up emotionally, physically, and verbally. Because of these beatings my li fe would be hell and there would be no safe place for me to go. Everybody would hate me, call me names, beat me up maybe even to the point of hospitalization. I may even end up gay-bashed and dead.."

These statistics and these comments are heart-breaking. While the issue of homophobic and transphobic bullying has been in the news lately, for students the reality is changing too slowly. As elementary teachers, we are in a position to have an impact by working with children when they are young.

When Gabe came home after being suspended, it was clear that something needed to be done. He endured daily comments "that's so gay;' "faggot," "fag," "f-g fag" (and worse epithets that that can't be printed here) with out once having any adult intervene. He begged me, "Please make it end and don't let any other kid live through this."

His father and I went to the school. We were taken seriously but it was very evident that the administration did not know what to do. I prepared a binder of best practices, documentation of legal responsibilities, and examples of school policies. We had a meeting at the school and the principal asked me if I expected him to do everything. I replied that I expected the board to shoulder its legal and moral responsibilities However, I was never allowed to meet with anyone beyond the principal: no superintendent would meet with me, and the director left a message through her assistant. Every door was shut in our faces. In April 2004, Gabriel filed a complaint with the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Schools are considered to be service providers and as such are obliged by law to provide a safe place for everyone. In Gabe's case they did not.

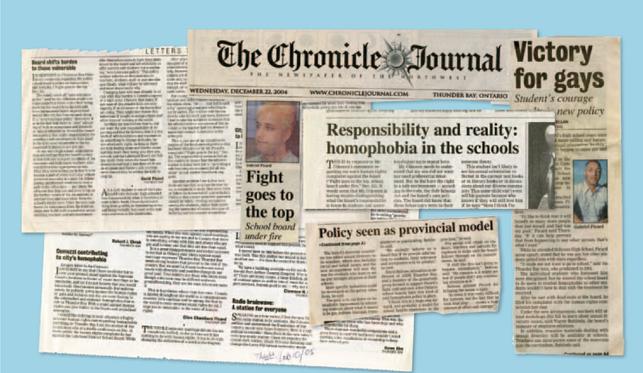

We waited for our complaint to be addressed. Gabe, his father, his sisters, and I worked behind the scenes. I wrote letters to my employer, the Lakehead District School Board, the minister of education, kept asking for meetings and found allies in Thunder Bay, my union and across Canada. Members of the LGBTQ community had been trying for years to have harassment in schools addressed. We formed a community group, and called a media conference in December 2004. My son was outed on the front page of the newspaper, we received provincial and national coverage, and the school board was put on notice.

A mediated Human Rights Settlement was reached in June of 2005.

Gay-Straight Alliances were to be facilitated in all high schools, anti-homophobia training was to be provided for teachers. Erasing Prejudice for Good and many other resources were purchased. The board formed a diversity committee. There were many good things in the settlement, some were implemented, and we thought we were done!

However, in 2006, when it became clear that not all the provisions of the settlement were put in place, Gabriel went back to the Human Rights Commission. We learned to never give up. It took a relentless resolve to make sure that the settlement was fully adhered to.

Fighting this battle was an all-consuming part-time job on top of my teaching duties and, in recent years, my job as local president. I have had some low moments in the eight years since my son and I ventured into the world of activism, but more importantly I have experienced unforgettable milestones, some of which will make lasting change in the lives of students.

My board now has GSAs in all high schools. The young people who are members and the adult facilitators are creating open and accepting environments. Administrators report that those students are the leaders in their schools, making change by being proactive. They have pink days, a Day Against Homophobia, movie nights – and the board supports them. This board is now embracing these students and is trying hard to make a difference with proactive measures.

Because of Gabe’s Human Rights complaint, the board now has LGBTQ resources in the instructional materials centre for teachers, LGBTQ community consultations for policy and procedures, and human rights on the agenda at every staff meeting. The board has provided human rights training for CUPE members and some teachers, and presented regional workshops on homophobia. It has a team of 10 teachers, administrators, and educational assistants trained to present anti-homophobia workshops. I am pleased to be among them. Specific policy dealing with homophobic harassment is still being worked on.

Is our work done? No. Will it ever be enough? I don’t think so, because as long as there is still one child who is harassed and bullied because of his or her sexual orientation or perceived sexual orientation there is still work to do. Fighting homophobic bullying is sometimes so critical that it may save a young person’s life. I always keep that thought in my mind and have told the board the same message over and over.

Teachers and administrators need the skills and tools to effectively address homophobia. We are often the only ones who will accept children for who they are. This type of discrimination is different from others in one way: students may not know if they will be accepted if they come out to their parents. I tell educators in workshops that it is our individual responsibility to ensure that all students are safe. It is also the law.

My mission has been to make sure that no one experiences what my son did. We are getting there. I thank Gabe for showing me the way.