Refugee Resettlement in Ontario Schools

Since the tragic photos of Ahmed Kurdi appeared in Canadian newspapers and on TV screens last August, the plight of asylum seekers from Syria, the Horn of Africa and other parts of Africa and the Middle East has mobilized and energized communities across Canada. This has led to an outpouring of support for private, blended visa and government-funded refugee sponsorship. Canada, and Ontario specifically, have reached out to bring scores of families – many of whom include young children – to live in our communities. Teachers and education workers have spent hours outside of their classrooms working toward sponsoring families. In many communities, students have been learning about the refugee experience by examining the issues surrounding asylum-seekers, fundraising for emergency relief or participating in the sponsorship process themselves.

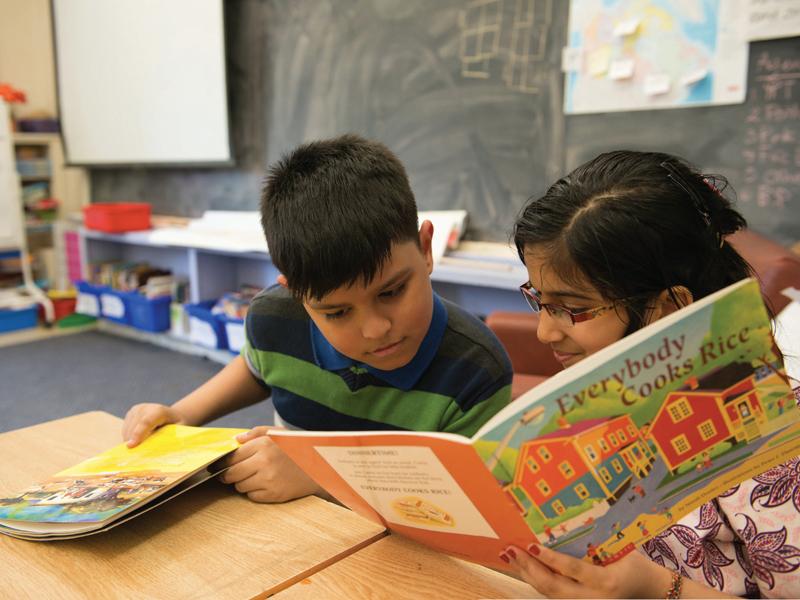

My classroom at Rose Avenue Public School, like most of our school, has students from all over the world. I like to think that many of my students’ experiences are reflective of other immigrant and refugee student experiences. Children frequently make reference to the reasons their families chose to come to Canada (education, job opportunities) or were forced to make the difficult decision to leave their homes (war, terrorism). My current Grade 4 students rarely differentiate between refugees and immigrants, all citing a need for people in their communities to seek better lives. While students make connections to the articles and stories we’ve read about refugees, refugee experiences seem to be limited to “over there” in the camps and on crowded boats; once the students come to Canada, they are all “New Canadians” at our school, regardless of status.

When refugees are fleeing their homes, after food and shelter are taken care of, one of the next things the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) does is set up schools. Education is universally acknowledged as one of the most pressing needs for children experiencing transition. Education is grounding and normalizes the refugee experience, providing much-needed routine to an otherwise uncertain existence.

Similarly, during the refugee settlement process, one of the arrangements that must be made immediately is to settle school-aged children into schools.

As frontline workers, teachers are often the first people – outside of immediate family – to be in daily contact with some of the most vulnerable members of newcomer communities. Along with social workers, settlement workers and counselors, teachers play a key role in helping students adjust to life in a new country. Our role in helping build up these often resilient children is critical; schools provide a safe place of learning and routines that will lead to building a solid sense of identity and belonging in children.

Trauma and Elementary School-Aged Children

Dr. Lloy Cook is a school psychologist who works with the Toronto District School Board. I spoke with her recently. In our conversation, Cook noted that any degree of trauma is trauma, and how students deal or don’t deal with it really depends on the individual. She indicated that the Canadian Medical Association, in a report on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), noted that “most persons who experience traumatic events have a favourable mental health prognosis.” This report acts as an assurance for those who may be looking for warning signs of PTSD, but not finding them.

Teachers and other education workers interacting with students who may have experienced trauma are advised simply to listen. Acknowledging the pain and suffering that the student has experienced is helpful, though teachers must also be sure to exercise due diligence in seeking out professional support through a settlement worker, social worker, guidance staff or school psychologist.

Teachers are advised to find out as much as possible about their students’ cultural backgrounds in order to better understand their experiences, even when there are language barriers. Teachers familiar with the Culturally Relevant and Responsive Pedagogy (CRRP) model will agree that this not only brings out the best in students from equity seeking groups, but also raises academic and behavioural expectations for all students.

Safe Learning Environment

Providing a safe learning environment is another way teachers can help in the transition for newcomer students. “As for any child coping with anxiety-provoking circumstances, the more structure and predictability the better,” says Dr. Cook. “A safe place includes having clear outcomes and expectations” so that students understand their roles and the roles of those around them.

Routines are very important to all children, but particularly to those who may have experienced some type of trauma such as living in refugee camps, fleeing their homes or losing a loved one. Students’ feelings of uncertainty and upheaval can be alleviated by posting and explaining schedules, announcing shifts and making sure transition times (class changes, lunch and recess) are predictable.

Teaching About War and Refugee Issues

Many teachers have used current events to teach their students about war from a different perspective than that of traditional Remembrance Day commemorations. We have been seeking out age-appropriate news articles and mapping the journeys of many migrant populations. As teachers, we are sometimes faced with materials that may act as triggers for students who may have experienced trauma, especially in conflict situations. When choosing materials to share with a class, it is important that students feel safe and included. Materials must not only reflect the experiences of the students, but also be sensitive to those experiences.

No amount of lesson planning and preparation, however, can determine what might be said during lessons and discussions in the classroom; sometimes an offhand remark or activity may trigger feelings of discomfort or negativity for students who have experienced trauma.

Teachers can help by ensuring students feel safe – by making themselves available and ensuring all students know where they can go if they feel uncomfortable. If a teacher recognizes a student’s discomfort during class discussions or other activities, she or he can provide alternate activities that are nonthreatening. Dr. Cook notes that math activities are generally considered “low-risk” as the language is “universal” and reassuring.

Dr. Cook also suggests having a variety of art materials available in the class for students to use – moulding materials, pencils, pastels, paints, found materials – as these relieve the pressure of talking and allow students the freedom to just draw, sketch, scribble or construct without language parameters or requirements. A quiet discussion with a student about what they have created can open doors to talking about how they are feeling. Or not. Dr. Cook stressed the importance of sometimes letting the student be; there are countless cases of children and adults who have experienced trauma and never choose to discuss what happened – they just move on.

In the classroom, anti-bullying initiatives, the creation of safe spaces, and programs that encourage empathy all work toward creating a safe place for all students to enter. If all students are expected to work together as a social group, to build and encourage behaviours that will bring about responsible citizenship, this will make transitions for newcomers easier.

Care for Teachers

Teachers who work with vulnerable students often act as the first line of support for those in their care, but can be susceptible to burnout themselves. Building a school support system of teachers who are working together with the students is a step toward self-care. Simply having colleagues share common experiences is critical to building solidarity. Like our students, facing difficult situations becomes much easier for us when we have a supportive team on which we can rely.

In a school like Rose Avenue, in spite of our large population (there are about 670 students from K–6), we strive to act together in a community to support our students and each other. Frequent collaboration between classroom and ESL/ELL teachers builds community, not only with newcomers, but also with us. Informal meetings about ways to support all our students – whether they are in our classes or not – occur frequently in the hallways, during recess and over email. It is our culture of inclusion that supports vulnerable newcomers, while supporting teaching staff.

Catherine Inglis is a member of the Elementary Teachers of Toronto.