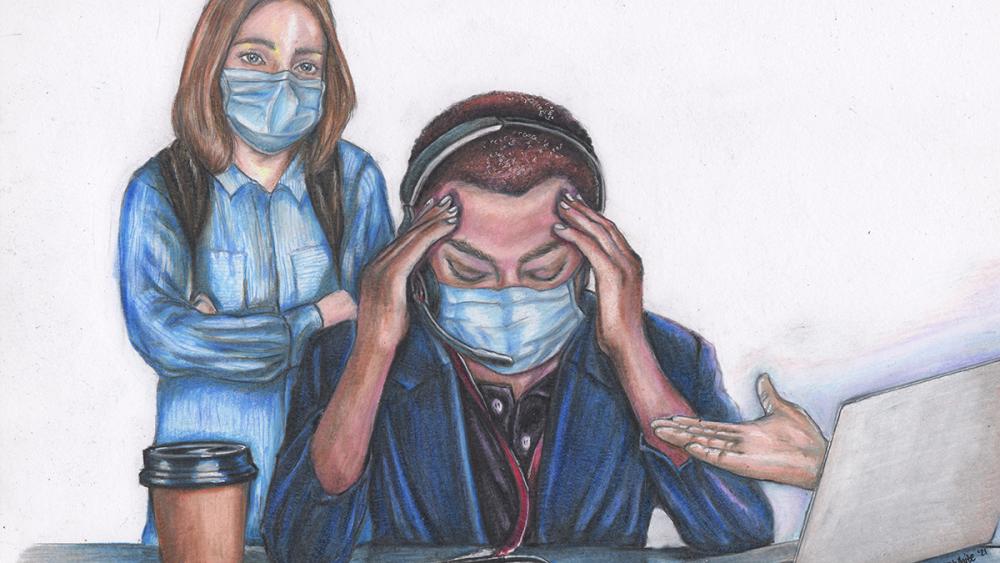

Illustration by Patrice White

Surviving Hybrid

The Perfect Storm

The classroom was organized, colourful and welcoming, but my thoughts were a confusing squall of what ifs. What if the technology doesn’t work? What if the hybrid students don’t feel connected? What if I can’t manage two classrooms in one? I was overwhelmed, underprepared and anxious.

That morning, I had gotten up extra early. Only this time, the nervous excitement that I normally felt at the beginning of a school year – the one that haunts you with dreams that you might accidentally sleep in – had been replaced with a painful and tightening knot. Over two decades in the classroom, and this first day as a Grade 7 hybrid homeroom teacher felt more unfamiliar and foreboding than my very first day as an educator. I got to school an hour before classes, walked into the classroom and completed my mental checklist:

Posters still on the wall? Check. ✔

Laptop cart plugged in? Check. ✔

Welcome message on the board? Check. ✔

Twenty-six start-up packages of consumables ready to be distributed? Check. ✔

Then came the questions that I had never before asked myself: Webcam and headset fully charged? Check. ✔

First Day Welcome slideshow and assignments scheduled to post on the Google Classroom? Check. ✔

Start-up packages labelled and ready to be sent down to the office for hybrid learners to pick up? Check. ✔

Will I need to send a Chromebook home for any hybrid learners? Not sure.

The list had doubled, and in that moment, so had my anxiety.

I looked at the equipment on my desk – webcam, Bluetooth headset, lanyard number one with photocopy card, classroom keys, photo ID and lanyard number two with the FM system transmitter for my hearing-impaired student. It was a tangle of strings, straps and wires that somehow had to make it around my neck and onto my head...all while wearing a mask and protective goggles. At that moment, I was not ready to be in two places at once. At that moment, I felt the literal weight of my new responsibilities. This was the beginning of the perfect storm.

Six and a half hours later, when the students had (virtually and physically) left for the day, I sat down to gather my thoughts. What had I learned?

- Everyone online is actually “hybrid;” some students will join while still on vacation, sick or quarantining from recent travel.

- Despite your best efforts, you might forget about the hybrid students.

- Despite your equity lens, you might ignore the hybrid learners.

- If you are wearing the headset, you will have to repeat what the hybrid learners say.

- In order to stay on camera, you might have to abandon flexible interactions for a lecture style.

My colleagues streamed into the hallway and the fatigue I felt was mirrored on their faces. I knew that we had a problem. Is this what we have to look forward to for the rest of the year? The question hung in the air. No one had answers. The first day of school is not supposed to feel this way, but it did. And for the foreseeable future, every day would feel like the first.

"Houston, We Have a Problem"

On paper, it is packaged as a natural solution. Several major boards of education sold it as such, highlighting its convenience and effectiveness with statements such as this one that appeared in an August 29, 2021 CBC news article: “The hybrid model keeps remote learners connected to classmates and teachers at the school they would normally attend... the model offers flexibility for moving between in-person and online learning under the same instructor, if needed.” When framed so simply, the idea of piping remote learners into their home school’s classrooms and effortlessly connecting them (in real time) with their peers and teachers was a possibility that a COVID-ravaged public wanted to believe. What was strategically muted in the narrative was that funding had been withdrawn for separate virtual schools, and this was precisely why the hybrid model was suddenly so prevalent.

Fast forward a few months, and parents, educators and students alike are beginning to see that in-person and online learning are about as agreeable as oil and water. With teachers having to post work activities in advance, and remote learners sometimes completing them before their in-person peers, it becomes hard to synchronize the learning pace of both groups. But alas, this was not the only misstep between the two models. The lack of resources at home – specifically access to laptops, blank paper, printers or even basic art supplies – creates an equity gap for the online students. In response, some teachers “flatten” their lessons, making sure to do only the activities in which a remote learner could fully participate. No more spontaneous games of silent ball or quick escapes into the great outdoors to continue an inquiry or investigation. This watering down of experiential learning not only robs in-person students of the dynamic knowledge-building that they had so missed while they were months online, but also magnifies the differences between each model’s realities and potentials. If one were to factor in the countless additional hours required for an educator to adapt instruction and subject content to electronic platforms, one might begin to understand how much the workload has increased. Perhaps the most egregious (and embarrassing) side effect of these two incompatible models is its creation of an unintentional culture of neglect and guilt. Because the teacher wants to be attentive to both learning styles but can’t physically duplicate herself, many virtual questions go unanswered and even ignored. That we are even being forced to choose between learners has become the reality. It is a confession that teachers are making with much more frequency and frustration, one that is contributing to an undermining of morale and confidence.

The hybrid model then is not the great middle ground or compromise. ETFO president, Karen Brown, defined it as more of a divide, one that ultimately separates the teacher from their best practices, and students from their best learning. Brown explained, “It was never a good solution...Hybrid might be convenient for some parents because they have students at home, but in regards to the quality of education, it’s not the best that our members could deliver, because their attention is divided – which means your child’s learning is divided.”

Thankfully, we are professionals who will always try to re-centre the child and reclaim their learning spaces. Our individual and communal efforts to bridge the gap have required a level of creativity that is not uncommon to dedicated teachers. We liaise with parents, assemble resource packages, send home materials and create instructional videos. Most importantly, we have tried to establish a more human connection with our hybrid learners by rejecting the equipment that the boards baked into their hybrid solution. That’s right! Within mere days (and for some, just hours) of hooking ourselves up to webcams and headphones, we ripped them off in favour of a less cumbersome and more authentic interaction with our students. Without the headset, their voices could finally be heard by the entire class and not just in my ear. Without the wired webcam constantly shifting, trying to refocus and occasionally sliding completely off the surface, students could have a more stable view of the board and our tasks. But before we left the tools abandoned in a pile, we were able to tap out one final and unified message: “Houston, we have a problem, but hybrid is not the solution.”

Who Suffers?

Who suffers? Everyone. The emotional, social, academic and even physical costs of the hybrid model are frankly indefensible. Teachers now live in a space of perpetual guilt; they are demoralized by the visible and daily reminders of what’s not working and who’s not working. They are defeated by their inability to effectively do the job of two teaching professionals at once. Even though it’s clear that this cost-saving measure is creating a vacuum at great emotional cost to educators and students, we struggle not to blame ourselves. ETFO York Region president, Tui-Sem Won, captured this dissonance well when she stated, “While it is possible to adapt many activities for a fully face-to-face or a fully online model, adapting for both models simultaneously puts teachers in an impossible situation.”

If one had to identify a group that is especially affected by this hybrid experiment, it would be our exceptional learners with LDs and IEPs. Unfortunately, with many unique challenges already complicating their everyday learning, the special education student is particularly vulnerable in the rickety framework of the hybrid classroom. With “teachers being given nothing more than a laptop, maybe an additional webcam or a microphone...and then being told to figure it out,” University of Ottawa assistant professor, Sachin Maharaj, said, summarizing the lack of investment, “the quality of the learning experience for students is severely compromised.”

Virtual schooling emphatically exposed the challenges of online learning. Emergency exemptions were put into place to allow students with the most complex learning needs to re-enter vacated school buildings. The decision was driven by public pressure and the fact that at-risk students thrive on one-on-one support. Imagine just how confusing it must have been for students when their teacher suddenly disappeared off camera, and her disembodied voice was heard addressing their in-person classmates? Tui-Sem Won, put a fine point on the plight of special education students, as well as those who are generally at-risk. In the June 2021 CBC News article, Public Education to suffer if teachers forced to teach hybrid classes this fall, unions say, Won made the following compelling comment: “The hybrid model is challenging when it comes to supporting the needs of special education students, and it disproportionately affects marginalized children...it doesn’t work well when classrooms do group work, if students at home lack certain devices.” And so, the hybrid model has simply widened a gap that has always existed between the mainstream and marginalized learner. In the CBC News article, Students pay the price for hybrid model of schooling, one concerned parent noted, “The hybrid model of school learning in pandemic times is a bit like a swim instructor teaching those in the pool, those watching from the deck, and others not even by the pool – all at the same time... There’s all sorts of things happening within a given classroom, but especially in the hybrid model...how do you get the teacher to be able to do all these things…at once?” The analogy feeds the critical narrative that the hybrid model will only contribute to the existing deficits in education. What’s more, it will also overextend the staff who see the suffering but are restricted by the very technologies that have been thrown at the problem. Certainly, the best response is in-person learning for everyone. With that option temporarily off the table, the separate virtual school is the more logical alternative. With dedicated staff members who are immersed in the same learning environment as their students, a virtual teacher can easily “be in the same pool” with all the learners. And so, at the risk of romanticizing a model that gave us its fair share of learning curves and curveballs, even on its most glitchy day, virtual schooling promises something that the hybrid model has not – survival.

Survival Mode

Getting students safely back into seats became the common goal this past fall. Above all else, this return would signal that we were rounding the corner and heading back to the old normal. It was an imperative backed by medical science, mental health advocates and plain common sense. In the same June 2021 CBC News article, union leaders unanimously stated that, “Under the hybrid model, the mental health of students will continue to decline as it has during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students not physically in the classroom will be shortchanged, and teachers will be put under enormous stress.”

Not only has the hybrid model challenged this skill, but also our understanding of good pedagogy. We have been forced to shelve or even unlearn the constructivist approaches of co-operative and inquiry-based learning. In its wake, the spontaneity of the classroom has been reined in by two antagonistic models, and the inequitable access to educational resources and supports have been exposed. We are all currently occupying an uncertain space, yet we will help our students and each other navigate it with patience, professionalism and a positive outlook for change. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it is simply this – we are all survivors, and this hybrid species of education will not outwit, outplay or outlast the voices and experiences that matter most.

At the end of the first school day, when the energy had left the building and my colleagues stood around looking defeated, the gap between the problem and solution widened exponentially. Education had hit yet another crisis point, a collision triggered by a poorly timed bureaucratic response to a pandemic that was constantly rearranging our classrooms and lives. Given the dire conditions and the glacial response to documented concerns and complaints, any solution would require our greatest asset – the ability to survive.

As survivors, we must reclaim the island by exiling the hybrid model. The Ford government’s lack of investment in students and staff have given it too much time and opportunity to run amok and erode our hard-fought gains. We must refuse the hybrid model, a plan devised by architects who did not consult with educators or consider the awful human and academic costs. Because the hybrid model was neither invited nor welcomed into our classrooms, it's time for us to move forward... without it.

Patrice White is a member of the York Region Teacher Local.