Advocacy from Asubpeeschoseewagong

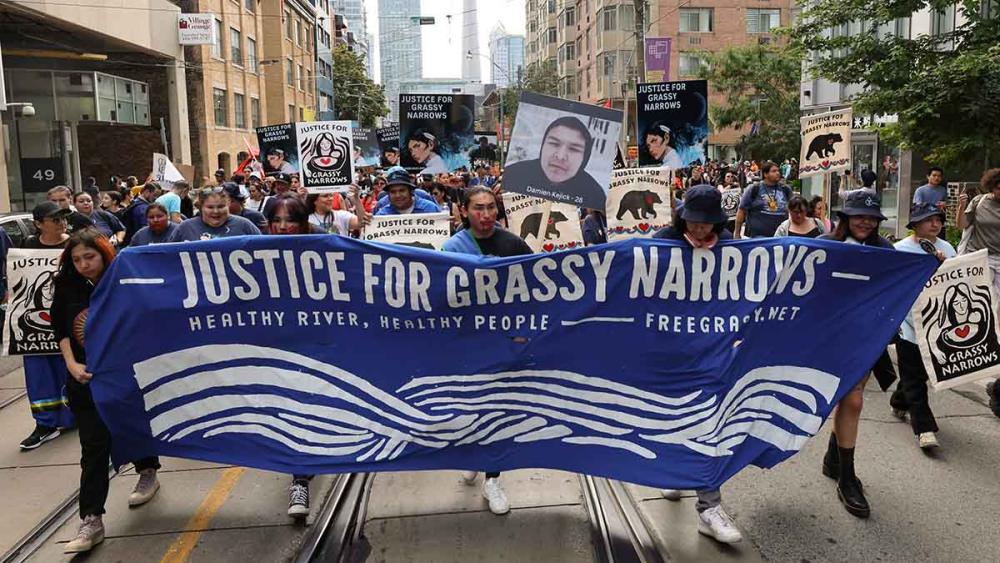

On September 18, 2024, more than 8,000 people marched from Toronto’s Grange Park to Queen’s Park in solidarity with members of Asubpeeschoseewagong (Grassy Narrows) First Nation. Called the River Run, this long-standing event raises awareness of the mercury contamination of the English-Wabigoon River in northwestern Ontario and advocates for compensation and cleanup, and for a future free of mercury. The event is intended to lobby the government about ongoing mercury poisoning, to educate the public, and to invite support and allyship. The community has been fighting for clean water in Grassy Narrows since the 1970s, with mercury poisoning contaminating the water supply for generations.

I’m from neighbouring Couchiching First Nation, an Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) community on Treaty 3 territory. Since 2010, Couchiching has been advocating for cleanup of a site contaminated by sawmill operations nearly 100 years ago. I hear similar stories from reserves across Canada, where people are struggling with the impacts of environmental destruction.

Though I only learned the term environmental racism in recent years, I realize that I have spent a lifetime living with and learning about it. According to the David Suzuki Foundation, environmental racism happens when development, policies or practices intentionally or unintentionally result in more pollution or health risks in Indigenous and racialized communities. It also includes patterns of unequal access to environmental benefits like clean water and air and proximity to parks. Environmental racism has serious impacts on health, well-bring and community outcomes. As an educator, I ensure that I integrate this concept into to my teaching about climate and environmental justice. As a member of a First Nation and a person whose history has been marginalized and misrepresented, I understand why it is essential when talking about communities that have been affected by environmental racism that we centre their activism and resistance

About 100 people from Grassy Narrows led this year’s demonstration to Queen’s Park, carrying signs made at an art build held in preparation for the rally. The impacts of mercury poisoning make the walk nearly impossible for some, but that didn’t stop people from travelling for the important act of advocating for their community. Some of the activists have been fighting for clean water for their community for decades; others are youth who were there for the first time. All of their lives have been profoundly impacted.

Travelling from Grassy Narrows to Toronto

In early September, Grassy Narrows member Chrissy Isaacs loaded her van for the journey ahead of her. Isaacs remembered her own beginnings in activism and knew how important this trip was for young people. Along with a dozen youth from the community, Isaacs was headed toward Toronto, stopping at towns and cities along the way to educate the public about the mercury poisoning that had been impacting their families for generations.

Each stop was a rally, where youth spoke about their experiences with the effects of mercury poisoning. They carried flags, banners and signs, and sang traditional songs for the water and the people. Their purpose was to educate people about what was happening in their community and to express their frustration and anger at being ignored by the government and industry leaders for decades. Youth are an essential voice in Grassy Narrows – advocating for change has been important to community healing from the trauma that is one of the social impacts of living with mercury poisoning.

By the time Isaacs’ group reached Toronto, many others had joined their caravan. Drum groups, elders, youth and children arrived from Montreal, Ottawa, Kingston, Hamilton, Guelph and Kitchener-Waterloo. Union members, students and other allies stood together to call for environmental justice.

Empowering Youth

Isaacs has suffered from mercury poisoning her entire life, and has watched her family and community suffer the effects as well. Symptoms can cause birth defects and cognitive delays, numbness and loss of coordination, general muscle weakness and deterioration, impaired speech, vision and hearing. Mercury poisoning can also lead to mental health struggles including depression and anxiety. Isaacs estimates that about 90 per cent of people in the community live with depression. Suicide rates are higher than average, and many people feel helpless and hopeless.

When Isaacs was 11 years old, she tried to take her own life. Thankfully, she wound up in hospital, where she met leaders Judy Da Silva, Chickadee Richards and others who were doing advocacy work to support Mohawk people at the Oka crisis (1990). These women knew the struggles that Isaacs faced and took her under their wing. Da Silva and Richards were working with Grassy Narrows youth and knew how important activism was to empowering and affirming young people. Isaacs says she finally felt like she had power and purpose in her life, nurtured through her community’s work with youth.

It was Asubpeeschoseewagong’s program Spirit of the Youth that was transformational for Issacs and other young people. The focus of this youth empowerment program was on environmental issues including mercury poisoning, caring for the land and water. The youth were trained as leaders and advocates, hosting conferences with their peers throughout Grassy Narrows territory and beyond, to discuss the important issues that their communities faced. The advocacy that they started has continued to support and strengthen their community.

Like others in her community, Isaacs became a strong advocate for her people. She identifies arts-based programming as an important wellness support. After what she describes as a “dark time” when many young people took their own lives, healing through art has offered youth a new way to have a voice. Multiple projects have resulted, including a 2016 project with N’we Jinan to produce Home to Me, a song about the land they live on. N’we Jinan Creative Studios provide youth with opportunities to collaborate with professional musicians and music producers for in-school or community-based programs ranging from one to three weeks in duration. These programs aim to empower youth to explore creative communication and share their artistic voices.

Finding ceremony and strengthening her own cultural beliefs and practices has been an important part of how Isaacs moved her advocacy forward. She has carried her community’s Sun Dance bundle, and now runs sweat lodges, which are an important cultural practice. These ceremonial roles are a great responsibility, given only to people who have prepared themselves.

Isaacs told me that she found her life’s purpose: to speak up about land, water and the environment. She does this not only for the health of the people but also for the health of the water, which is an essential part of the culture and ceremonial life of the community.

Isaacs urged me to tell educators to “teach the truth. Share the stories of Indigenous people as strong advocates, powerful voices for the Land and water.”

Supporting the Fight for Justice

The story of Grassy Narrows and the River Run can be used to educate students about environmental racism, advocacy and the persistence and strength of Indigenous Peoples. The first River Run in 2010 is well documented and can be shared in the classroom to generate discussion and drive inquiry.

There are also numerous articles on more recent River Run rallies and supports for educators who want to teach their students not only about the inaction of the government and the impacts of environmental racism but also about the activism and resilience of Indigenous communities.

Follow freegrassy.net for regular updates, news and events in Grassy Narrows. You can sign up for periodic newsletters, check out the take action page and find resources to share in your own networks.

Research the work that community members are doing to build capacity and take back power. Anishinaabe women in Ontario organize water ceremonies and water walks. Attend any open events, listen to what community members have to say, and share this information with others. Look for events near your community to learn more.

Look at your own community or region. What types of industries have negative environmental impacts? Consider things like railway lines, transit routes, highways, disposal sites. Who is most at risk of being affected by these? Is there an opportunity to do community organizing or support ongoing efforts?

JoAnne Formanek Gustafson is an Anishinaabe of Gojijiing and a member of the Rainy River Occasional Teacher Local.

Resources

N’we Jinan Artists Home to Me

youtube.com/watch?v=EgaYz8YWsO8

Treaty 3 Connections: Learning about Worldview of Indigenous people.

teachmag.com/treaty-3-connections

Amnesty International. 2020. The youth rising up against Canada’s mercury crisis.

youtube.com/watch?v=JgasHx0pJxM&t=8s

Danks, S. 2024. Raven Trust. Event Recap: Movement Building and Justice with Judy Da Silva

raventrust.com/campaigns/grassy-narrows/

Interview with Judy Da Silva

youtube.com/watch?v=X8XTY8Qny-s