Black Lives Matter: Izida Zorde in Conversation with BLM Toronto Organizer LeRoi Newbold

IZ: How did Black Lives Matter begin? What was the impetus behind the movement internationally and how did the Toronto chapter start?

LN: In February of 2012 in Florida, 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, on his way home from buying Skittles and iced tea, was shot to death by a neighbourhood watchman named George Zimmerman. After six weeks of complete inaction by police and thousands of protests across the country, a special prosecutor charged George Zimmerman with murder. He was acquitted. A six-person jury found Zimmerman not guilty to charges of both second-degree murder and manslaughter. Zimmerman walked free.

This happened in the context in which Black people in the United States are killed routinely by police, security personnel or white vigilantes every 6 to 28 hours. It happened in the context in which police routinely kill Black children and youth with impunity. Trayvon Martin’s name would be joined by the names of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, 7-year-old Aiyana Jones, 13-year-old Tyre King, 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, 18-year-old Michael Brown and 21-year-old Alex Wettlaufer in Canada. In Los Angeles, Patrisse Cullors and Alicia Garza started to tweet #BlackLivesMatter. In the tweet resided an affirmation. Black children are not disposable. Black children are inherently valuable and worth fighting for. Together with Opal Tometi, Cullors and Garza founded #BlackLivesMatter.

The #BlackLivesMatter movement has grown to include 35 official chapters, of which #BlackLivesMatter – Toronto (BLMTO) is one. It formed following a grand jury’s decision not to indict Darren Wilson who shot and killed 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri after stopping him for jaywalking. #BLMTO started off positioning itself in solidarity with Black communities for what was happening in St. Louis, Baltimore and New York City. It was not until later that we started to focus more intentionally on issues of police murder and anti-Black racism in Canada.

IZ: What are the specific demands and calls to action from Black Lives Matter?

LN: The 35 chapters of #BlackLivesMatter function fairly autonomously. Sometimes we convene to set some network priorities, but for the most part, people know their cities best and they develop demands that reflect the needs of their own communities. BLMTO develops demands based on particular campaigns or actions that we do.

BLMTO has focused on the police murders of Jermaine Carby in Brampton and Andrew Loku in Toronto. Jermaine Carby was a young Black man killed during a carding stop, and Andrew Loku was a South-Sudanese refugee father of 5 killed by police in his home in Toronto. When we commit to supporting a family who has a lost someone to police violence, it is very important to centre their voice and let them set priorities as the people who are most directly affected, so often our demands will focus on the wishes of the family. Beyond that, our demands centre on accountability; we want to know the names of the officers who killed Andrew Loku. In the United States, if an officer kills someone, the officer’s name is released because that is a public concern. Here in Canada we don’t have that measure of transparency. We demand that the officers who killed Andrew Loku and Jermaine Carby be removed from rotation and charged with murder. We demand an effective method of civilian review and appropriate discipline for officers who use excessive force or practice racial profiling. This is what the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) is supposed to do, but does not effectively do.

We also have a list of demands related to the quality of life of Black people in Toronto. For example, in fall of 2015 a 13-year-old Black girl at Amesbury Middle School at Jane and Lawrence was pulled out of her class for wearing her natural hair. Following that we made several demands that center around our education system in Ontario. We demand that healing spaces be created for Black-identified students who have experienced anti-Black racist violence in the school system. We demand the creation of a Black students’ council to advise the Ontario Ministry of Education and our Toronto school boards on issues such as widespread student disengagement, culturally inappropriate framing of the curriculum and standardized testing. We demand a divestment in the School Resources Officer program and the removal of all police from schools. We demand the creation of representative district-level advisory boards comprised of Black parents, Black students and Black community members. Without the approval of these advisory boards, no Black student in Ontario should face suspensions, expulsions or placement in behavioural or Section 23 programs.

IZ: What impact do you think this movement is making? How is it changing kitchen table conversations in Canada?

LN: I believe that here in Canada, the #BLM movement is carving out space to acknowledge and talk about anti-Black racism as a distinct form of violence that is pervasive in our society and shapes our immigration system, our health care system, our school system and our urban planning. It is carving out space for Black radicalism, for us to dream of and celebrate alternative ways of living and organizing society that have nothing to do with the state.

For example, at Black Communities Take Back the Night in 2015, we did a showcase where people could watch theatre skits about how we can deal with issues of family violence or mental health crisis without depending on police. At #BLMTOBlackCity (a 15-day occupation of Toronto Police headquarters), our community created a space where over 100 Black artists performed, people stood around in the ice and snow talking about Black liberation and the history of Black resistance in Toronto, people set up a community healing station and people negotiated our safety without ever depending on police to “protect” us. At #BLMTO Freedom School, Black parents and youth developed our own curriculum for teaching the history and current movements of Black liberation. For the duration of this program we self-determined that our children would learn about freedom, they would be taught by Black community members who love and cherish them, they would be treated with respect and dignity, they would eat healthy food and their education would come at no financial cost to their families.

IZ: What are the connections between violence like carding and police brutality to forms of oppression such as economic and social precarity, the racialized wage gap and gender-based violence? How do these connect for you?

LN: Poverty and police violence are very connected, and our city is set up in a way to facilitate that. In 2011, the city of Toronto named 13 “priority neighbourhoods” for “improvement” based on the fact that they fell below the “neighbhourhood equity score.” These 13 neighbourhoods included every one of the most densely populated Black neighbourhoods of Toronto: Jane and Finch, Malvern, Lawrence Heights, Kingston-Galloway, Weston-Mount Dennis and Flemington Park are examples. Part of the purpose of naming these neighbourhoods as “priorities for improvement” was to justify programs like TAVIS.

TAVIS is a neighbourhood-focused policing program that increases policing in particular areas of the city. Increased police presence means an increase in carding. Carding is a practice of police “randomly” stopping people, questioning them and recording data about them. One analysis found that 40 per cent of the names collected in the carding database are the names of Black people, despite the fact that Black people make up less than 6 per cent of the population of Toronto. Despite a lot of public outcry about how carding violates peoples’ human rights, the Ontario government failed to abolish carding, and instead came up with a guide on how police forces should conduct carding. We know that TAVIS leads to violent raids of neighbourhoods where no illegal substances are found and innocent people are traumatized. We know that carding leads to murder by police. It led to the murder of Jermaine Carby.

Precarity and gender also play a huge role in police/state violence. Almost 100,000 migrants were detained in Canada between 2006 and 2014. Migrants are the only population in Canada who can be legally detained without even being charged with a crime. It’s horrific, and people are dying in detention. Black transgender women and sex-working women are harassed regularly by police in Toronto.

IZ: How do you respond to the assertion that some people have made that “All Lives Matter?” Can you talk about why this statement is particularly problematic in this moment in history?

LN: Do I believe that “all lives matter” in the terms of the intrinsic value of human life? Yes. Do I believe that “all lives matter” is useful or relevant as a political assertion or ideology? No. I believe that saying “all lives matter” instead of “BlackLivesMatter” demonstrates ignorance about the political reality we are living in, and furthermore, it demonstrates a commitment to ignore Black suffering in order to focus on literally nothing.

Firstly, #BlackLivesMatter focuses on addressing the ways the state is violent towards Black people and the ways the state is waging a war on Black bodies. It focuses on dealing with police routinely killing Black people, our children being told that they can’t learn at school, our children being abused by police officers INSIDE their schools, Black trans women having an average life expectancy of 35 years old, Black trans people being unemployed four times more than white cis-gender people, Black women being the fastest growing prison population in Canada, Black families being 40 per cent more likely to be investigated by CAS than white families in Ontario. It is clear that the state doesn’t treat people as though all their lives matter – so why are people politically asserting that?

Secondly, if people want to create an organizing body that is just humanist and focuses on the value of all lives, they should not use a spin off of the name #BlackLivesMatter. It is disrespectful and inconsiderate to steal the intellectual property of hard-working Black women warriors to create an ideology that pushes Black people to the side again. People who purport that “all lives matter” really haven’t done any work to demonstrate their commitment to improving anyone’s life.

IZ: How important is solidarity in social movements? How does Black Lives Matter connect with Indigenous movements, queer political movements or the labour movement? What do you want to see more of?

LN: Understanding that there are many parts to who a person is or to what impacts on a person’s oppression is important. Black people are not just Black. We can be Black and queer, Black and Muslim, Black and poor, Black and disabled, Black and transgender, Black and sex-working, Black and Indigenous, Black and incarcerated. And this movement needs to be for everyone. It is no longer acceptable or realistic for us to fight against anti-Black racism and put away the other aspects of what makes us ourselves to be taken up another time. The time is now.

#BlackLivesMatter is not in solidarity with queer political movements. We are a queer political movement. BLM was founded by three queer women and benefits from the leadership of queer and transgender people across its 35 chapters. Our politics are queer. Queer politics have been anti-racist, anti-police violence and pro-access since their inception.

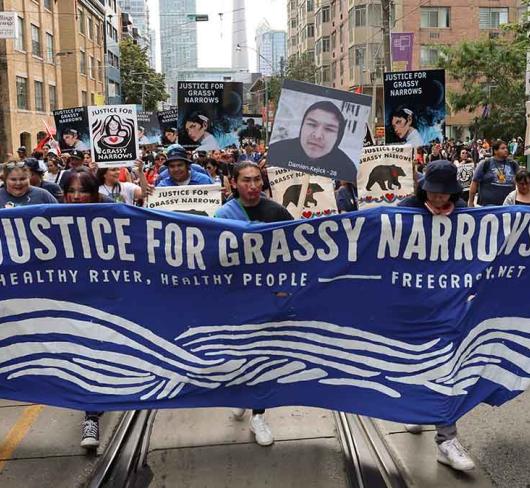

Being in solidarity with Indigenous people is also part of #BLM’s mandate. This summer, members of #BLM traveled to North Dakota to be in solidarity with Indigenous people at Standing Rock to oppose the building of a pipeline that would carry crude oil and harmful chemicals through Indigenous land. Indigenous elders acted in solidarity with #BLMTOBlackCity, watching over us as we slept and helping us to understand the history of solidarity between our communities. It is important to be in solidarity because we are experiencing similar realities at the hands of the state. Indigenous women are going missing and being murdered on our highways as Black people are being killed by police and nobody is being held accountable.

IZ: What about the labour movement? Do you see a connection there? Is organized labour a source of support?

LN: These movement times are an opportunity for organized labour to really step up and support Black lives when historically in Canada they have failed to do so. The Coalition of Black Trade Unionists and other unions have come out in support of #BlackLivesMatter – Toronto in terms of backing and also on the ground. People are understanding that we need to address not only the growing death toll at the hands of the state, but also the quality of Black people’s lives including both workers and those who are without work because of barriers.

But another concern is how police unions consistently stand in the way of political transformation. Organizers in cities like Chicago and New York are starting to target police unions because certain collective agreements help to ensure that police cannot be held accountable when they murder people or use excessive violence. This is part of the reason that reforms that have been recommended and even mandated by the government have not gone through. Police unions need to be held accountable as well because they are protecting workers who are racially profi ling and who have murdered people.

IZ: What are the policies and cultural changes that you would like to see come out of this movement? What do you see already?

LN: I would like for people to see that oppressed people have power. Individually we have power, and together as communities we have power to create change. We don’t have to make it high up in a system in order to have a voice and we don’t have to settle for choosing between the lesser of two evils when it comes to electoral politics. We don’t have to and cannot afford to accept things as they are.

Cultural change is important because the system of anti-Black racism cannot change without changing people’s hearts. Forty per cent of Black children in Toronto are not graduating from high school. That has a lot to do with people’s commitment to the cultural deficit model. It has to do with teachers’ belief systems about Black parents, Black children and Black communities. In our home countries we are achieving. Barbados has a higher literacy rate than Canada. In Jamaica, Black children learn to read at age three and four. We need to understand that the problem is not with our culture. The problem is with the system of white supremacy.

IZ: How do you see the role of teachers and education in Canada? What is your experience as a teacher and what do you try to pass on to your students?

LN: Teachers have many times played important roles in Black liberation movements. In the civil rights movement, Black teachers were instrumental in the South because they were trusted and respected members of community so when they took to the street that brought legitimacy to the movement for some people. Classrooms are political, whether it is intentional or not. Teachers have the power to challenge or confi rm stereotypes, to highlight or make issues invisible, to build up young people or make their path more challenging for them.

I teach in the TDSB at the Africentric School and “BlackLivesMatter” is at the crux of my classroom politically. When you’re living in a time when Black children can be shot in the street with impunity you have to be taught to love yourself and that you’re valuable. You have to repeat it to yourself. I confirm the reality of anti-Black racism in our systems for my students and I teach them not to recreate state violence in their interactions with other Black people. I try to teach them to love Blackness in themselves and in others. I teach them that when we have been oppressed, Black people have fought and won. We won in the Haitian Revolution, we won the right to be citizens of Canada and we will again.

IZ: What wisdom can you pass on to other teachers who want to talk about systemic racism with their students? Are there any particular resources that you would recommend?

LN: If you don’t love Black children simply quit your job. We can be taught pedagogy and praxis, but love cannot be taught. Don’t look for fault in your students, their parents, or their communities. See the characteristics of Black families and neighbhourhood as assets not hindrances. If you take credit for student success, take responsibility for their failure as well, because it is your responsibility. If you lack skills to serve your class or school community, learn those skills and do better. Don’t underestimate the capability of Black children (even and especially young Black children) to politically analyze reality. In terms of resources, #BlackLivesMatter – Toronto developed some excellent arts-based resources for teaching about Black liberation through our Freedom School, which we hope to release publicly soon. Local Black bookstores are excellent resources as well.

LeRoi Newbold is a member of the Elementary Teachers of Toronto.