Emma: Learning About the History and Impacts of Residential Schools

Emma Lafortte was my grandmother’s younger sister. We knew very little about Emma, except what our grandmother shared. She and her sister were sent to St. Joseph’s Residential School in Fort William (Thunder Bay) in 1906 when they were five- and six-years old. Emma died when she was nine and was buried somewhere close to the school. My grandmother’s recollection was she was woken very early in the morning and brought to a fresh grave. She was told her sister had died and to kneel and pray. Over the years my grandmother made inquiries to find where her sister was buried but to no avail. She knew the residential school had been relocated from the Fort William First Nation to Port Arthur when the land was sold to the railroad. It was later destroyed in a fire and a memorial now stands where the school was once located. My grandmother believed the grave, along with other graves, was ploughed over by developers. We were told that Emma, like other children who lost their lives, became ill and there were no doctors or hospitals in the area. My grandmother had no idea her sister had taken ill or was admitted to hospital as it was the policy in these schools to separate siblings by age and gender. She also told us it was common for the older children, herself included, to dig graves when children died at the school. When the first discovery of 215 bodies of Indigenous children in a mass grave in Kamloops was reported, and subsequent mass gravesites were discovered, our family made the decision to once and for all find out what happened to Emma.

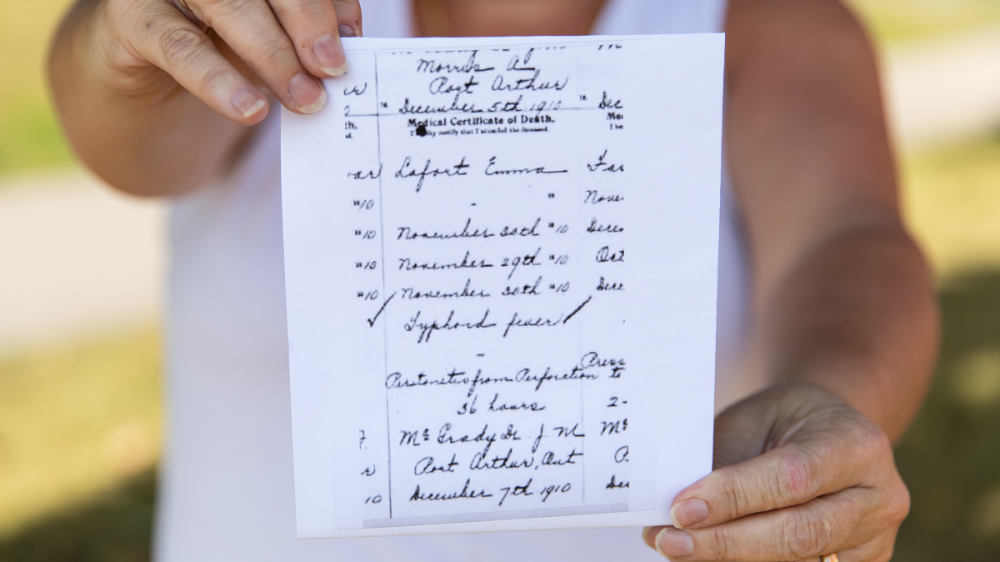

We found Emma’s death certificate. She was admitted into the Port Arthur Hospital November 27, 1910 and died 10 days later. Cause of death was listed as Typhoid Fever but also included burst appendix. Typhoid fever was never the cause. Emma suffered an excruciatingly painful death from a burst appendix; the high fever was the result of her body trying to fight the infection. The hospital was either lacking proper medical staff to know what was going on or not willing to take care of Emma or both. It was not uncommon for Indigenous children attending residential schools to be denied necessary medical treatment, misdiagnosed and neglected.

Through record searches, the Nishnabe Askis Nation and author Tanya Talaga, we found Emma in an unmarked grave at St. Andrew’s cemetery in Thunder Bay in June 2021. On September 13, 2021, our family had a repatriation ceremony in which soil from the unmarked gravesite where Emma was buried was placed alongside our grandparents’ gravesite in Garden River First Nation. It will be in proximity to my grandmother’s mother, her mother and my grandmother’s youngest sister who are also buried in the cemetery. We will have done our very best to bring Emma home to rest with her family. The same cannot be said for many Indigenous children who perished in these schools.

Over 5,000 gravesites have been discovered on the grounds of former residential schools. Some of them have been bodies of children as young as three. During the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings, residential school survivors testified to mass gravesites in many schools. Other than an apology by the federal government, no other action to find out what happened to these children has occurred.

The legacy of residential schools in Canada has had a lasting impact on the survivors and their families. Indigenous Peoples in Canada experience the highest levels of poverty: a shocking one in four Indigenous peoples (Aboriginal, Métis and Inuit), 25 percent, are living in poverty and four in ten, 40 percent, of Canada’s Indigenous children live in poverty. A review of Statistics Canada suicide rate data for Indigenous people shows that one of the leading causes of these high rates of suicide is the intergenerational impact of the residential school system. Analysis of the high rates of incarceration of Indigenous people suggests that most of the increase is due to increased severity in the treatment of Indigenous offenders by the criminal justice system. Similarly, the number of Indigenous prisoners has increased because more Indigenous offenders are receiving prison sentences and for longer periods. Historical and present day racism, colonialism and apathy continue to contribute to the ongoing challenges faced by Indigenous people. Talking about residential schools at one of ETFO’s past annual meetings, Indigenous Manitoba MPP Nahanni Fontaine said, “we are talking about what is happening and has happened to human beings. Some of them were babies, just babies.”

As educators, we must teach more than just awareness of the legacy of residential schools. Changing a name or removing a statue is not going to educate students about the justifiable grievances Indigenous Peoples currently have about treaties, access to clean water and racist policies that continue to impact Indigenous Peoples today. We all need to learn about the policies underlying residential schools, their intent and the impact they had and continue to have on Indigenous and non-Indigenous people across Canada. The Indian Trust Fund is one such example. When treaties were signed, resources extracted from these lands generated large revenues, creating jobs in primary and secondary economies. Oil and gas are an example. A share of the revenues from these resources is then placed in a trust for Indigenous people in each treaty. This is to provide support for each community to pay for education, health care, social services, utilities (clean drinking water) as a few examples. Currently, the trust stands at three billion dollars but is controlled and administered by the federal government which decides how much to distribute to Indigenous communities. If Indigenous communities were afforded funds necessary to help, for example, survivors and their families, the statistics might look very different.

The apology offered to Indigenous people on June 12, 2008 noted the federal government’s fiduciary responsibility under the Indian Act in the development of residential schools. The Indian Act was part of a long history of assimilation policies that intended to terminate the cultural, social, economic and political distinctiveness of Indigenous Peoples. It was used to override the authority of the treaties. A comprehensive study of treaty history and the Indian Act must take place in Canadian classrooms.

Pope Francis has agreed to meet with Indigenous leaders, residential school survivors and Catholic clergy in Canada in November 2021. Hopefully this meeting will take place. The Catholic Church owes the Indigenous people of Canada an apology for its role in the development and operation of residential schools and the impact it had on children and their families. But apologies are not enough. All those involved, including governments, must release any information they have about what happened to the children who were forced to attend and then perished in these schools. Their families, communities and all of Canada have a right to know the truth. More than 5,000 children were the victims of the atrocities committed in these schools. Emma Lafortte is just one.

Beverly Fiddler is a member of the Durham Teacher Local.

Resources for Teaching About Residential Schools, The Indian Act and Treaties

Residential Schools

Project of Heart – projectofheart.ca/

100 Years of Loss: The Residential School System in Canada legacyofhope.ca/100-years-of-loss-5/

First Nations Caring Society – fncaringsociety.com/

When We Were Alone by David Robertson, illustrated by Julie Flett - HighWater Press 2016

The Secret Path by Gord Downie, illustrated by Jeff Lemire, Simon & Schuster Canada 2016

As Long as the Rivers Flow by Larry Loyie and Constance Brissenden, Illustrated by Heather Holmlund - Anansi Press 2005

Shi-shi-etko by Nicola I. Campbell and illustrated by Kim Lafave - Groundwood Books 2005

Fatty Legs by Margaret-Olemaun Pokiak-Fenton and Christy Jordan-Fenton and illustrated by Liz Amini-Holmes and Foreword by Debbie Reese - Annick Press -2010

The Orange Shirt Story by Phyllis Webstad, and illustrated by Brock Nicol - Medicine Wheel Education 2018

Good for Nothing by Michel Noel - House of Anansi Press 2004

Sugar Falls by David A Robertson, illustrated by Scott B Henderson – HighWater Press 2012

Treaties

We are all Treaty People by Maurice Switzer, illustrated by Charley Herbert, 2017

Treaties in Canada Education Guide and Worksheets – thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/studyguide/treaties-in-canada-learning-guide-and-worksheets

On the Path of Elders – pathoftheelders.com/-2009

Ontario Indigenous Education Strategy – edu.gov.on.ca/eng/indigenous/

Indian Act

CBC – Teaching Guide: The Indian Act cbc.ca/radio/secretlifeofcanada/teaching-guide-the-indian-act-1.5290134

drive.google.com/drive/folders/1a_inMC-AJ8nsoCoY8uQOxFy39kYMRD14 by Leah-Simone Bowen & Falen Johnson of 'The Secret Life of Canada'

First Nation Metis and Inuit Education Resource: Engaging Learners through Play by Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario 2017

Aboriginal History and Realities in Canada (1-8) by Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario 2008