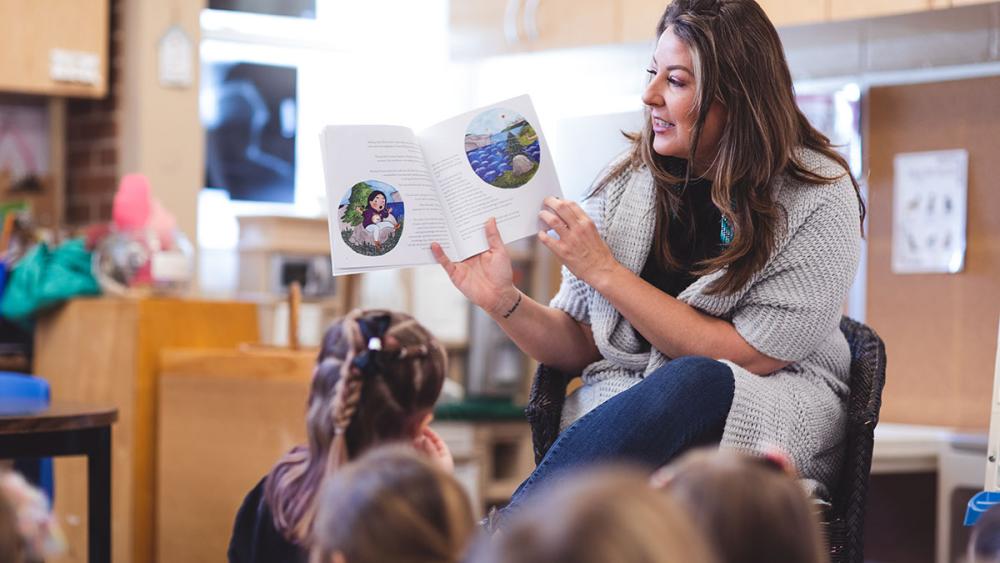

Photo by Christine Cousins

Indigenous Storytelling and Environmental Connections

As a Métis woman and educator for over 20 years I still feel anticipation when I come across relevant First Nation, Métis and Inuit focused materials to share with my students and colleagues, especially when they are centred around storytelling and a connection to our environment. I currently live, play, love, teach, learn and unlearn on the unceded, unsurrendered lands of the Algonquin People in a small rural school in the Renfrew County District School Board. As a prep teacher I have the privilege to teach students all the way from Kindergarten to Grade 8. For me, integrating an environmental focus and the art of storytelling into curriculum areas comes naturally and makes an invaluable impact.

The Kindergarten students light up when I arrive to their class with Moose, an Indigenous puppet I picked up during my last trip to British Columbia. This beloved puppet was an immediate ice breaker and he loves to share his wisdom about emotions as we gather for our sharing circle.

As part of our STEM project this year we have learned about the importance of igloos to the Inuit people. The students’ excitement was nothing short of electric when given the challenge to build their own igloo with the materials provided. We learned about an igloo’s importance, how and what Inuit hunted and their respect for both the land and animals.

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge into Science and Social Studies classes has been seamless. My Grade 5s have enjoyed some warm cedar tea and a smudging ceremony as we gathered to discuss the lands on which we live, the fur trade and the various levels of government and their impact on Indigenous Peoples and the environment. I thrive on rich discussions with my students about the importance of First Nation practices in our daily lives and the importance of caring for the environment and one another.

One thing I hear often from other educators is that they simply don’t know where to start when trying to integrate more Indigenous knowledge into their daily classroom practice. My response is…just start. Begin with your own classroom community. Your students have unique families, experiences and interesting stories they are eager to share. Encourage them to become researchers and recorders of their own stories. Have your students brainstorm why oral history is important. Have them discuss traditions and celebrations in their families and how they differ and are similar to those of their peers. Listen and learn from one another. Have them present their own stories about their family history, caring for the Earth, personal accounts of respecting others or something with an embedded life lesson or moral. Not only will this experience provide insight into your students’ lives but it will build a foundation of trust, understanding and compassion. The art of storytelling can sustain communities, validate experiences, nurture relationships and serve as a form of important cultural recognition for the Indigenous Peoples of Canada. Stories are used to teach lessons, inspire dreams, entertain people and pass on knowledge and wisdom. Storytelling can bring people together.

Teachers can use storytelling to develop oral literacy skills within their classrooms. One common theme in Indigenous storytelling is the importance of land and animals. Our beliefs are rooted in the interconnectedness of the world. Providing students with the opportunity to build a strong connection with land, water and animals ultimately helps them build humility and respect for everything and everyone around them. This can, in turn, create a more empathic school and classroom community. A focus on nature and the environment can create eco-wellness. Eco-wellness can create happiness and has endless benefits for our mental health.

Storytelling is so much more than just the oral delivery – it takes the development of both patience and trust. When preparing to listen to a story students need to recognize that we are not just using our auditory senses. We are also visualizing the characters and letting their emotions surface. As Jo-Ann Archibald writes, “Some say we should listen with three ears: two on our head and one in our heart.” I love to use a feather or talking stick to signify who the speaker is. This visual cue reminds students that when someone is holding the talking tool they are the ones doing the talking and we are the ones doing the listening. Listening skills are paramount to Indigenous Peoples’ teaching and learning. Listening was and continues to be critical in traditional cultures as the first step in committing something to memory.

Each morning at our school we hear a land acknowledgement. Explore the land on which your school is located, both past and present. Narrating the landscape can be an eye-opening experience for your students. Look for opportunities to incorporate placebased learning into your teaching practice. To start, have students sit in a circle outside. Have them get into a comfortable position and, if they would like, to take off their shoes and place their feet on the grass. Now have them close their eyes. Take the next three minutes to simply listen…in silence. Afterwards discuss what they heard, felt and thought about. In traditional Indigenous culture silence has a value and purpose. It offers opportunities for personal reflection. Being in, looking, touching and breathing in nature is so important to our overall well-being. Nature is wondrous, sparks curiosity and gives us a sense of something bigger than ourselves.

Storytelling can take place anywhere. Take your instruction and learning outdoors whenever possible. Indigenous education doesn’t have to be a daunting task. It is something that can be woven into all your curriculum focuses. One of my favourite books to grab as we head into the outdoor classroom is Sila and the Land, by Ariana Roundpoint, a writer of the wolf clan of the Kanyen’kehá:ka people, born and raised in Akwesasne, Shelby Angalik, a writer from Arviat Nunavut, an Inuit hamlet on the western shore of Hudson Bay and Lindsay DuPré, a Métis social worker and educator based in Southern Ontario. This book tells the story of a young Inuk girl who journeys across the North, East, South and West. Through her travels she meets different animals, plants and elements that teach her about the importance of the land and her responsibilities to protect it for future generations. This one read aloud can spark all sorts of inquiry and curiosity.

What animals roamed across your school yard at different points in time?

What are traditional medicines and what are their benefits?

What will the environment be like in 20 years?

How can we do something every day to help the environment?

Another favourite book of mine is We Are Water Protectors written by Carole Lindstrom and illustrated by Michaela Goade in response to the Dakota Access Pipeline protests. Find out what bodies of water are near your school and what they are used for. Are there particular fish, passages or issues with the waterways? Make a mind map to explore all the things that would be affected if that water was no longer there. Have your students share memories on the water. Have they tried canoeing? Do they like fishing, paddle boarding, swimming? Have they heard a loon calling? Take these experiences and have them write a spoken word piece drawing on poetry components and the importance of protecting our water.

If you’re looking to build your own classroom story collection be sure to check out Goodminds, your school library and the Indigenous Coach with your board for literature that fits with your teaching practices and curriculum. After reading a story, ask students to reflect back on the plot and character development of the story. Ask them to think about the lessons and apply them to their own lived experiences.

In drama, I’ve provided students with various images that relate to the land and Indigenous knowledge that they can make personal connections to. I have them research a story to share with the class. Their focus is on the use of voice and body expression. I always stress the importance of their intonation and verbal imagery. Having them use a mirror and check their facial animation can be a huge benefit. Provide your students with a drama theme; seasons, water, animals, and have them create a short play about the importance of this aspect to Indigenous Peoples in the past and present. Their plays should clearly connect nature to the climate crisis, through a solution-focused lens. The use of props can be an impactful addition to storytelling. Collect some found materials in nature, add some animal puppets and have the students draw art pieces or make masks.

Storytelling empowers Indigenous voices. When teachers preserve their stories listeners are reminded of Indigenous Peoples’ strength and resilience. Indigenous stories are significant because they are anchors of resistance. They are also ways of preserving the language, the power and the meaningfulness of the spoken word. These stories should be heard, remembered and learned from.

Teri-Lyn Flemming is a member of the Renfrew Teacher Local.