Pages Into Pathways

In a world where systemic barriers persist, women’s voices in activism have proven to be transformative forces for social change. These voices bring critical and impactful perspectives that are all too often sidelined or silenced altogether. When women speak truth to power, they illuminate experiences that challenge prevailing narratives and expose critical gaps in our collective understanding of justice and equity.

Ontario’s Language curriculum offers educators a powerful framework to foster critical consciousness in elementary students through the stories of influential women activists. Drawing on Paulo Freire’s definition of critical consciousness as the ability to recognize social contradictions and take action against oppression, this approach transforms language instruction into a catalyst for societal transformation.

As pedagogical theorist and teacher-educator Gloria Ladson-Billings noted, critical consciousness is the most vital aspect of culturally relevant pedagogy. By integrating the narratives of women activists into language teaching, educators fulfil the curriculum’s Strand A goal of developing understandings of diverse identities and perspectives while students practise essential transferable skills like critical thinking and global citizenship.

This integration creates authentic contexts for students to analyze “culturally diverse texts” while developing core language competencies. Through engagement with activist voices, including those from First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities, students learn to question norms that produce inequalities – exactly what Ladson-Billings envisioned when she described schools as places that should “destabilize, create disruption, and disrupt the status quo.”

As students explore these powerful examples, they strengthen their sense of identity and responsibility. They develop digital literacy skills by examining relationships between text forms, content, and creators, ultimately learning that transformation begins with awareness and culminates in action – fostering the “empathetic, respectful, and inclusive” engagement that Strand A seeks to nurture.

In education, the exploration of identity is not just an academic exercise; it is a source of inspiration and a vital process that shapes how we interact with our students and colleagues. To illustrate the significance of self-examination in understanding resilience and resistance, we can draw inspiration from three remarkable women, Rosa Bonheur, Viola Desmond and Natasha Kanapé Fontaine, through books written by Canadian authors.

Each year, our school participates in the largest recreational reading program in Canada – the Ontario Library Association’s Forest of Reading. The program encourages a love of reading through carefully curated book selections for different age groups.

In 2025, the books nominated for the prix Peuplier category (French picture books) collectively explored themes of identity, family dynamics, discovery, empathy and activism through diverse storytelling approaches.

One of the books that was chosen in the 2024 prix Peuplier category was Pas de chevaux dans la maison! La vie audacieuse de l’artiste Rosa Bonheur (No Horses in the House! The Audacious Life of Artist Rosa Bonheur) by renowned Canadian author Mireille Messier, illustrated by Anna Bron.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) was a pioneering French painter renowned for realistic depictions of animals and rural life. Working in a male-dominated art world, Bonheur faced numerous challenges, yet her passion for art defied all gender-based conventions. In 19thcentury France, societal norms dictated strict gender roles, and women were expected to wear dresses. For a year and a half, Bonheur dressed in tailored suits and trousers in order to sneak in and sketch horses at a horse fair held weekly in Paris.

Bonheur was one of only 12 women in 1850s France who were given special permission by the police to wear trousers. Her reasons were practical – as an animal painter who often worked outdoors, Bonheur needed freedom of movement to capture equine subjects in their natural settings. Wearing pants allowed her to navigate environments with ease, especially during visits to rural areas and livestock fairs. Bonheur’s bold decision to defy oppressive dress restrictions for women not only showcased an artist’s commitment to her craft but also made her a symbol of women’s liberation, advocating for autonomy and self-expression. Bonheur’s story reminds us of the importance of challenging societal norms and the power of pursuing one’s identity.

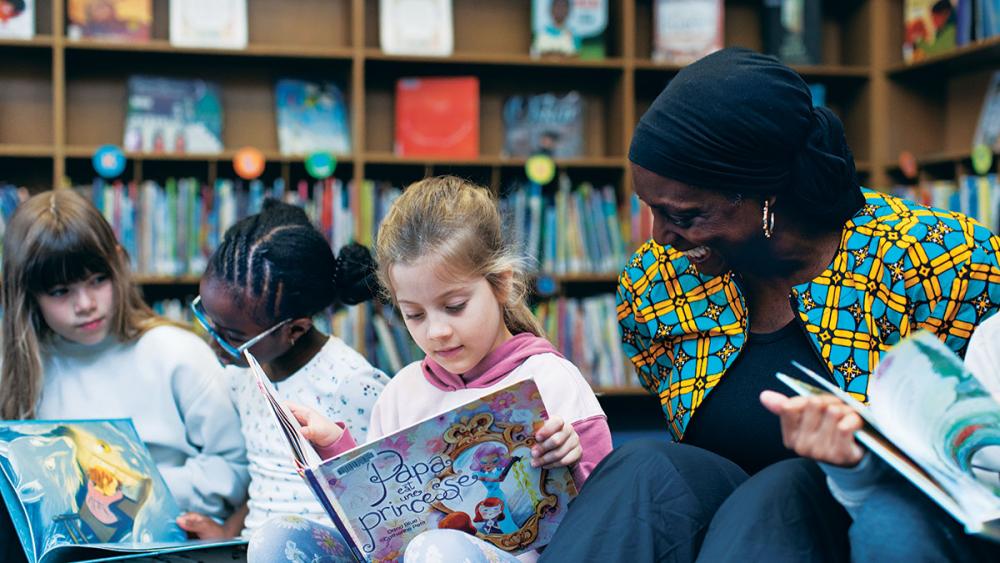

Another story chosen for the 2024 prix Peuplier category was Papa est une princesse by Canadian author Dana Blue (illustrated by Catherine Petit). In a modern twist on classic narratives, Papa est une princesse reinterprets the Cinderella fairy tale through the eyes of a young girl accompanying her drag performer father to a performance. This story highlights themes of identity, transformation and acceptance. As the father prepares for his drag show, the narrative explores the beauty of self-expression and challenges traditional gender roles. Blue’s work encourages readers to embrace diversity and celebrate the unique identities that each individual brings to the world.

Students easily found connections between Rosa Bonheur’s story and Papa est une princesse. By comparing Bonheur’s practical defiance of gendered clothing norms with the drag-performing father, students recognized powerful parallels across time periods and narratives. Both stories illustrate how clothing choices become acts of personal autonomy and political resistance. Bonheur’s rejection of gendered clothing restrictions helped forge a path toward greater gender expression freedom. Her trailblazing courage to prioritize authenticity over convention established precedents that eventually enabled modern celebrations of gender fluidity, like the proud drag performance depicted in Papa est une princesse. Comparing the stories deepened students’ critical consciousness by revealing how individuals challenge restrictive societal expectations through personal choice, creative expression, courage and celebration of self.

The stories we tell about historical figures shape our students’ understanding of their identity, resilience and potential for change. As educators, it is vital to approach the narratives of others – particularly those from historically marginalized communities – with a critical lens. The story of Viola Desmond serves as a poignant example of how a singular lens can obscure a broader legacy.

Desmond, often heralded as a heroine of social justice for her refusal to vacate a whites-only section of a Nova Scotia movie theatre in 1946, has become a symbol of anti-racism and civil rights in Canada and abroad. In many educational contexts, her story is framed primarily around this act of defiance, which is frequently celebrated as a pioneering act against systemic racism. While this narrative is indeed significant and worthy of recognition, it is critical to understand that it only captures a fleeting moment in Desmond’s multifaceted life.

Desmond was not merely a courageous figure reacting to social injustice; she was also a groundbreaking entrepreneur who made significant contributions to the Black haircare industry. As the owner of a successful beauty salon, she created innovative products tailored specifically for Black hair, a market often neglected by mainstream businesses at the time. Moreover, she established her own beauty school, training numerous Black women to enter an industry that otherwise offered them limited opportunities. These aspects of her legacy showcase a woman who not only resisted oppression but also sought to uplift her community through education and business.

When educators present Desmond solely as a civil rights icon, they inadvertently restrict students’ understanding of her broader contributions and the complexity of her narrative. This narrow framing can lead students to view historical figures through a limited lens, often as symbols of resistance rather than as fully realized people with diverse identities and accomplishments. Such simplistic portrayals can perpetuate stereotypes and overlook the richness of Black experiences and achievements.

By adopting a more nuanced approach to storytelling, educators can empower students to appreciate the multifaceted identities of historical figures like Desmond. They can explore her life as a tapestry woven from threads of entrepreneurship, innovation and social justice. Incorporating various sources – books, documentaries, and interviews with historians – can provide a richer context that highlights Desmond’s significance in multiple spheres.

Moreover, engaging students in critical discussions about the stories we choose to tell can foster greater empathy and understanding. Educators might ask questions such as: What aspects of Desmond’s life are often overlooked? How does framing her primarily as a civil rights icon shape our perception of her contributions? Encouraging students to analyze different narratives will help them recognize the power of storytelling in shaping perceptions.

The way we frame the stories of figures like Viola Desmond significantly influences how students perceive not only these individuals but also the larger issues of race, identity and social justice. By expanding the narrative beyond singular moments of resistance to encompass the broader scope of their lives, we can inspire students to see the complexities within history and encourage them to recognize and celebrate the diverse contributions of all individuals.

By linking past struggles for justice with present-day activists who address similar themes through different mediums, students sharpen their critical consciousness and can better understand how these issues remain relevant and evolving.

Natasha Kanapé Fontaine, an Innu poet, author, interdisciplinary artist and activist from Pessamit, Quebec, uses her powerful voice to advocate for Indigenous rights and environmental issues. As a child growing up in Quebec, Kanapé Fontaine did not speak a lot of Innu. When she was an adolescent, she sought ways to reappropriate her Innu language and culture. Today, Kanapé Fontaine’s poetry often delves into themes of identity, resilience and the connection to ancestry. This work serves as a reminder of the importance of representation and the need to honour diverse voices within educational contexts. By sharing her experiences and insights, she inspires others to reflect on their own identities and the impact they have on their communities.

I first discovered Kanapé Fontaine’s work while engaging in an equity and bias check of the French as a Second Language curriculum draft in 2013. I sought to provide educators with examples of contemporary Frenchspeaking Indigenous women who had a significant impact on society, and I stumbled upon Kanapé Fontaine’s poetry on YouTube.

At 20, Kanapé Fontaine wrote “Nous nous soulèverons” (“We Will Rise”), a poem that centres on Indigenous resistance, revival and reclamation. More recently, she published her first novel, Nauetakuan (No-weh-ta-Kwan), which means “a silence for a noise” in Innu. The novel affirms how reconnecting to lineage and community can transform Indigenous futures.

This most recent work from Kanapé Fontaine, written for adults, brings to mind a children’s text I have read with students addressing Indigenous revitalization of language, cultural practices and community knowledge to create pathways for self-determination. When reading Be a Good Ancestor by Leona and Gabrielle Prince (illustrated by Carla Joyce), our youngest students reflect on who they are as result of who came before them. Students are challenged to consider how their actions today will impact future generations.

Through her poetry and prose, Kanapé Fontaine invites readers to consider their place in an intergenerational continuum, much like Prince’s children’s book does for younger audiences. Kanapé Fontaine’s work demonstrates how reclaiming Indigenous languages and cultural practices serves not only as personal healing but as a revolutionary act that reshapes collective futures. By sharing powerful expressions of Indigenous resistance with students, educators create vital opportunities for all learners to reflect on their own cultural inheritances and responsibilities to those who will follow them.

As we embark on this journey of self-exploration and critical consciousness, let us draw inspiration from the stories of Rosa Bonheur, Viola Desmond and Natasha Kanapé Fontaine. Their experiences highlight the power of identity and the importance of embracing diversity in our classrooms. By reflecting on our own identities and fostering inclusive environments, we can create a more equitable and just educational landscape for all students.

Karen Devonish-Mazzotta is a member of the Elementary Teachers of Toronto Local.