Resources for Thinking About Truth and Reconciliation

In June 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued a series of recommendations about education relating to First Nations, Métis and Inuit (FNMI) students. They highlighted the need for funding Aboriginal schools in order to include traditional teachings. They also made clear that there is a pressing need for age-appropriate mandated education about residential schools for all students at all grade levels.

It is a challenge for many teachers to implement these calls to action. There is a fine line between empathy and appropriation, and the difficulty for a teacher not already familiar with the complex nature of FNMI history in Canada can lie in not knowing how and where to begin in an informed and sensitive manner.

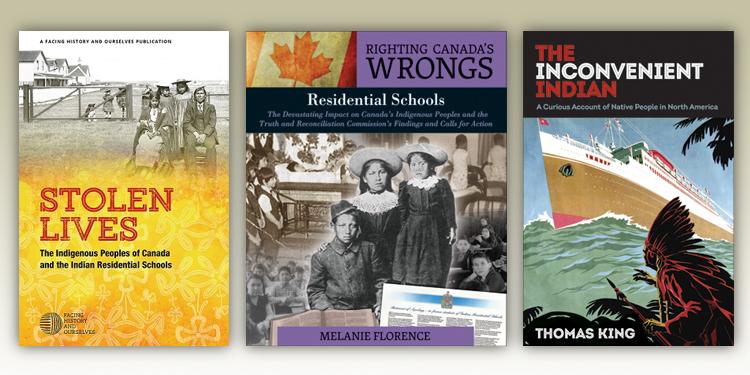

A great start would be to explore some of the excellent books about FNMI history and education that already exist. Four such books that together provide a strong introductory perspective are First Nations, Métis and Inuit Success (Deb St. Amant), Righting Canada’s Wrongs (Melanie Florence), Stolen Lives (Facing History and Ourselves) and The Inconvenient Indian (Thomas King).

In First Nations, Métis and Inuit Success, St. Amant provides many recommendations for how to build community, incorporate traditional teachings and create a classroom in which FNMI students will feel valued, challenged and safe. She recommends that educators learn as much as possible about their students’ cultural backgrounds, embed Aboriginal perspectives into all aspects of the curriculum in culturally-responsive ways, reach out to the community, critically explore materials in order to uncover cultural biases, employ handson, land-based learning and, above all, form meaningful and cooperative relationships with students. She emphasizes the need to create a classroom in which there is a sense of order and predictability while providing differentiated instruction responsive to students’ needs. The book provides a myriad of suggestions about how to implement these and other recommendations and includes many concrete ideas for teachers to try.

In the introduction to Righting Canada’s Wrongs, Florence notes that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called for the implementation of age-appropriate mandated education about residential schools. Her book fills that need in a comprehensive and moving manner. It employs primary and secondary sources in readable, eye-catching ways. It is a text that is equally valuable for teachers wishing a primer in the history of residential schools and for students in virtually any grade within the school system. In particular, the remarkable selection of photographs, coupled with strong, simple text, can serve as provocations for young students, or as the starting point for in-depth critical analysis for older students. The inclusion of many first-person accounts keeps this resource grounded in real experiences. Links to online audio and video resources that supplement the text help to bring the information alive. This book is highly recommended for use in the classroom.

Stolen Lives also explores the history of residential schools in Canada but is more squarely aimed at older readers. It contains a detailed history of Canada’s first peoples from the time of first contact through the rise of the Indian Act, the creation of residential schools, to the present time. It explores how the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the apologies from the government and Anglican Church are leading to national conversations about how to achieve reconciliation. The text is divided into many smaller sections, each of which is followed by several questions for consideration and deeper thought. There is no doubt that this text would be a valuable resource for teachers of intermediate students.

Finally, The Inconvenient Indian is an excellent way for teachers to gain some perspective about the history of interactions between FNMI peoples in Canada and those who came to settle here. Its narrator is, like many of Thomas King’s narrators, an ironic figure, employing humour and a wry perspective that welcomes the audience into the conversation, even as it challenges perspectives. Its chatty tone is reminiscent of an oral tradition in which important information is passed down through entertaining stories, trickster figures and speaking directly to the audience in a tongue-in-cheek manner. But behind the banter lies encyclopaedic, devastating information about the history of FNMI people in Canada. It is an outstanding read that will do much to help teachers gain an understanding of the challenges facing Indigenous education in Canada.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation notes that part of its mandate includes “teacher education and preparation for teaching a difficult but critical part of our history, always with the view of evoking reconciliation and respectful relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students” (umanitoba.ca/centres/nctr/resources.html). Furthermore, the Ontario Elementary Curriculum includes expectations at every grade level relating to equitable inclusion of the history and perspectives of FNMI students. Teachers play a unique and critical role in facilitating reconciliation and healing in Canada. It is a daunting task and one that will evolve and change over time as more is understood about our collective history. But it is also an honour to take a fundamental part in ushering in an era of change. Books such as the ones listed above are a great place to start.

Susan Currie is a member of Peel Teacher Local.