Stop Streaming Black Kids Into Special Education

I had precisely two minutes to get back to my homeroom class on the second floor. The problem was that I was stuck on the first floor, waiting impatiently for the copier to choke out the second half of my math handouts. I had a vague plan to run up to class and then ask a “responsible student” to retrieve the copies from the office. As I darted into the hallway, I was met by a zig-zagging sea of students. Excuse me! Sorry, guys! Let’s pick up the pace, please! I was getting nowhere fast. So, I veered off my usual path and flew up another stairwell. Literally seconds away from my classroom door, my name wafted out of the small classroom across from it. “Hey Ms. White! How are you?” I spun around and stuck my head through the open door. Staring back at me were a handful of young students whose names I couldn’t quite remember. They were excited to see me, so I gave in to the moment. We chatted for the few seconds I no longer had, and I told them that I couldn’t wait to teach them in Grade 8. Just then, the Special Education Resource Teacher (SERT) arrived, which was my cue to leave. The French teacher met me at the door with a forgiving grin. I thanked her profusely and tried to return her smile, but my heart was troubled. I was disoriented, and not by the new route to my classroom or the missing handouts, but by those beautiful brown faces who had been separated to meet their unique learning needs. As a teaching professional, I got it. What I didn’t get though was why most of them looked like me.

Let’s start with the good news – Ontario has begun the long overdue process of ending the deleterious practice of streaming. In a recent article, the CBC reported that “The province’s math curriculum will be the first to be de-streamed as of September 2021.” No doubt, this is a step in the right direction; however, it doesn’t address the indiscriminate (and discriminatory) practice of streaming. Unfortunately, directing low income and racialized students away from academic programs starts long before choices such as “academic,” “applied” and “locally developed” ever show up on a high school course selection sheet. One might argue that this is precisely where the concern and action should begin – at the elementary level. Systemic racism disproportionally misplaces Black and racialized students in special education. Seen through a deficit model, these students are expected to underachieve by uncritical educators who are privileged by their culture and race. The anticipated failures that are projected onto Black and racialized students sometimes become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Not only are they triaged into special education by practitioners in dire need of anti-bias and anti-Black racist training, but as York University professor Carl James has noted, they are often held there by a system for which streaming is an “essential component of the architectural structure of inequity and a significant scaffold in the system of racism and education.” Thankfully, there are special education teachers and teams working to build connections that support and humanize every student. Fact is, on more than one occasion, I have heard confused colleagues question the placement of a racialized student in special education. And while this highlights an emerging awareness, it will not grow into advocacy and transformative change unless this practice is critically challenged.

Numbers Don't Lie

“One-quarter of students in less affluent schools have been identified as special needs, compared with just 13 per cent in higher incomes areas… Research out of the Toronto District School Board broke down the discrepancies even further, finding that Blacks and South Asians are overrepresented in special education and under-represented in gifted programs. White students are ‘significantly overrepresented’ in gifted programs, as are East Asians.” (Rushowy, 2013)

My work site is nestled in an affluent neighbourhood. Relative to other areas, we do not seem to lack for resources, but the number of Black and brown students in that Student Support Center (SSC) just doesn’t reflect the economic privilege of the region. Something else is at play, a marker of identity with such a complicated and troublesome history that it reared its head even in this cocoon of wealth. At first, I did not want to entertain the idea that race was a significant reason why so many of our Black students had been streamed into special education, but a simple exercise made it abundantly clear that I should. I decided to list every Black student who had passed through either my homeroom or rotary classes. Considering the fact that there were so few of them, it was a short list. When all was said and done, only 28 names and faces had surfaced. Wow, just 28 students over 21 years of teaching! What rattled me most, however, was the disproportionate number of these students who had been designated as special education. I was further distressed at the patterns the numbers revealed:

- 18 out of 28 Black students were determined to be special education

- 12 out of the 18 students were male; 6 of 18, female

- 6 of the 18 students were siblings

There was definitely a problem, one that in my experience has been intergenerational and particularly hostile towards Black males.

Special Education is Not the Problem

For countless students who have benefited from carefully crafted and executed Individual Education Plans (IEPs), special education is part of the solution and not the problem. To underscore its importance, the Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario (LDAO) explains that “knowing that there is a specific reason for … difficulties can be a great relief. A better understanding of … strengths as well as … weaknesses can be an important first step towards building self esteem and developing more effective coping strategies.”

Regrettably, special education has been unfairly implicated in an elaborate system of marginalization. Indeed, racialized students are sometimes shuffled into special education by practitioners who don’t understand the urgency to respond to diversity or might lack the confidence to do so in a meaningful way. Fortunately, special education programs have undergone several critical revisions, becoming more nuanced and responsive with each revolution. Nowadays, what used to be described as Disadvantages and Difficulties, have been replaced with the less stratifying term, “at risk.” Still, it foreshadows the colonialist thinking that children who fall outside of the white lines of education need to be removed from the mainstream – not the opposite that mainstream education needs to change to support a diversity of students and families. And so, when undergirded by a framework of thinking and speaking that focuses on deficits, special education can become another system of oppression.

The Silent Dilemma of Deficiency

Without the conscious use of anti-bias and anti-racist tools, schools and their agents (teachers, administrators and education workers) can mindlessly reproduce inequality. One of the most efficient vehicles for this forecasting and rigging of success are deficit models of thinking and teaching that according to University of Toronto professor Dr. David Livingstone, “deny or denigrate the continuing capacities of working-class people to create cultural forms and meanings for themselves.” In other words, the marginalized and racialized bodies that often occupy these blue collar spaces are not permitted to influence and guide curriculum with their cultural and lived experiences. And so, the practice of imposing mainstream perspectives and expectations, not only shifts goal posts based on one’s race and gender, but also factors into how a child sets and achieves goals. As published in a 2016 Statistics Canada report, while 94 percent of Black youth aged 15 to 25 want to earn a bachelor’s degree or higher, only 60 percent thought they could. It is tragic to see that there is a 34 percent gap between desire and expectation. This manipulation of outcomes may be invisible to many, but it doesn’t escape its victims. In fact, so powerful is the narrative that Black youth will underachieve and overreact that it highlights the silent dilemma and malignant practice of streaming.

Streamed Into Anger

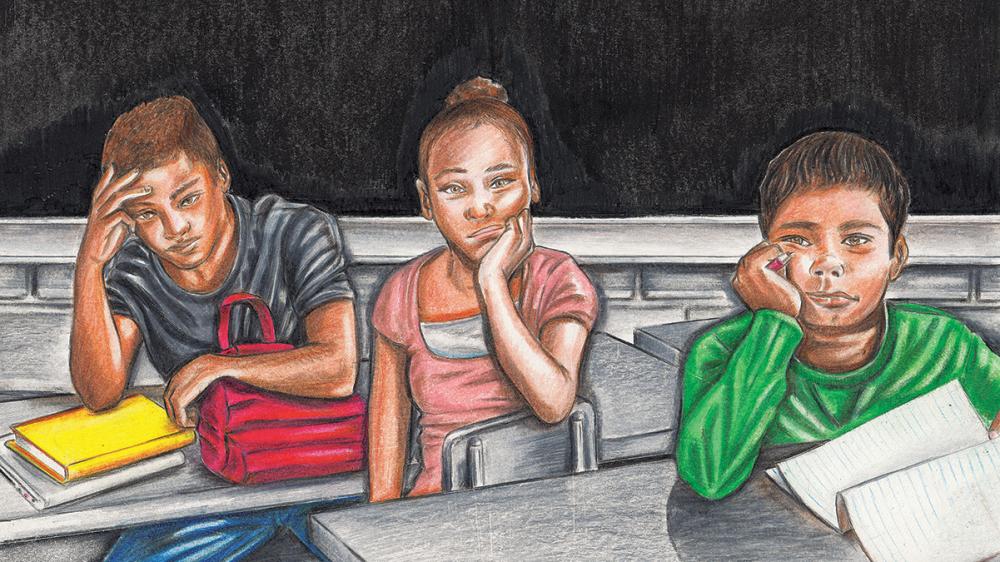

The insidious roots of streaming have finally been exposed within Canada’s school systems. Ontario’s largest and most diverse board, the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), has frequently grappled with accusations of systemic bias and anti-Black racism, but neighboring boards are also now being publicly forced to work out their troubling relationships with race. The Peel District School Board (PDSB) recently shared jarring accounts and disheartening statistics of anti-Black racism predicated on streaming. For example, in a recent article, “Anti-Black Racism in Education,” author Tammy Axt revealed that, “In grade 9 and 10, Black students make up approximately 10.1 percent of the student population, but they are represented in the courses as follows: in academic 7.7 percent, in applied 21.7 percent and in locally developed credit courses 25.4 percent.” While these statistics shocked and frankly embarrassed many, the revelation only confirmed what Black students in special education already know or suspect – there’s no real expectation they will ever navigate their way out. When the only options presented to them as they leave elementary school are “locally developed” or “applied” courses, the suspicion morphs into reality. And when transition teams boldly fire up the machine of micro-aggressions to declare that the child will “get a job, or better yet, become an NBA player” it is hardly a compliment. In fact, such false platitudes are nothing more than a veneer for vile stereotypes. Is there any wonder then why the trope of the “Angry Black Student” persists? Unfortunately, one doesn’t have to look long or hard to find reluctant special education learners in shades of black and brown. Not only are they disengaged, but at times defiant and even depressed. This is when the “spec ed” label needs to be reassessed through a multicultural lens.

Representation Works

The poison of deficit thinking is not easily countered, but a possible antidote to this toxin is representation. I first realized this during my second placement, when a Black special education student insisted that there was no way I was trying to become a teacher. “Black people can’t be teachers!” he declared. He suggested other jobs and careers – ones steeped in media stereotypes. For the first week of my one-month placement – when teacher candidates traditionally observe the class – he held stubbornly to his disbelief.

The fact that I was busy distributing handouts, taking notes, circulating in the classroom, but not teaching, certainly didn’t help to move his imagination along. By the end of my placement, however, he had come around to the idea of my presence in his, or for that matter, any classroom. Still, the moment that I will never forget, is the one that probably changed us both. On the last day of my teaching block, after I’d bid a tearful farewell to the class, he lingered at the door. He pressed a homemade card into my hand and between sniffles whispered that I was going to be a good teacher. But what made my heart positively sing were his parting words – “Miss, I might even try this teaching thing.” He was a special education student who had dared to dream outside the box into which he had been placed. Helping him to push the boundaries of the limitations that had been imposed on him had been the highpoint of this experience. Representation works.

That being said, representation is not enough; without connection and advocacy, it is a fail. This can’t be the exclusive mission of Black teachers, for as Vancouver-based Black activist Cynthia Blain has emphatically stated, “We also need non-Black teachers, educators and concerned citizens to be part of the work, and not just rely on the Black community to educate everyone else.” (Peng, 2019).You see, non-racialized teachers add volume, allowing us to finally amplify what racialized teachers have done silently for years.

I was a part of this shadow army. Lest I be accused of fanning the flames of white guilt, I would assemble Black students quietly. Whether it was to share a favorite food, listen to music, swap stories or discuss racism, we deliberately conducted these meetings out of sight. You see, it was important that I not recreate the “frightening” visual of Black kids huddled in the hallway, a scene that once prompted a colleague to hiss, “They’re always up to no good when they’re together!” Looking back, I now see the tragic irony of the situation – I was trying to control the optics and give students a voice, all the while suppressing my own. So, with the double bind of being a marginalized teacher within a marginalizing system, what can we all do to support the racialized students in the parking lot of special education?

The Way Forward

With 21 years of hindsight at my disposal, I can now do my small part to move the discussion forward. The complicated history of race and schooling necessitates a more culturally responsive public education system, one driven by practitioners who are ready to do the hard work of unlearning decades of racism. For teachers, challenging cultural norms and confronting bias has to become everyday thinking and practice. Towards this end, we must:

- See colour! Unfortunately, colour blindness will lead to underrepresentation. When we allow ourselves to acknowledge imbalance, we are motivated to recalibrate the scales of social justice.

- Root out bias and perform cultural checks. Ask yourself – “What don’t I know?” Most importantly, seek out credible resources to fill the voids and provide cultural context.

- Check your blind spots. You may not see or understand specific actions, words or performances because they are hidden by dominant norms.

- Actively de-stream. Do not track racialized students into the arts and athletics and away from academics. Have conversations with them about their passions; take note of their intellectual curiosities. Push them towards their lights.

And so, change begins with the acknowledgement that education is not inherently a great equalizer; we have to work to make it that way. Educators must be committed to naming and challenging the hidden agendas and power structures that demean and stream racialized students into hostile spaces. Finally, we must progress into actions that move theory into practice. For students of colour and their families, special education must not become a “parking lot” for differences that the system does not tolerate. Rather, the backbone of the “architectural structure of inequity” must be broken. Most importantly, it needs to be replaced with an anti-racist framework that is promoted and protected by committed educators. This is the way forward.

Patrice White is a member of the York Region Teacher Local.