Teaching for Social Justice Using an Activist Approach

I’m sometimes asked to explain why equity education work is still needed in schools. People might say that the social injustices of racism and sexism and classism (not to mention all the other human rights violations) are issues more relevant in the past than in the present. Others wonder whether elementary schools are the right places to explore such weighty issues. My response, in a nutshell, is that teaching equity has never been more relevant, and that it’s never too early to start teaching about fairness. Social justice education needs to be in the fabric of our daily teaching work because every day social injustice is woven into the fabric of our students’ lives.

Social justice and social justice education, nurture human potential and challenge injustice. In this way, social justice is both process and goal. A democratic and socially just education system that is responsive to everyone and serves all groups equally and well, is a key mechanism for engaging in that process and communicating that goal. If we don’t address real issues of fairness in schools, we simply aren’t furnishing our kids with a complete education or a truthful story.

The Tale of a T-Shirt play

Consider a recent school field trip to a local theatre where grade 3 and 4 classes at my son’s school attended a short, alternately funny and serious play centred around an ordinary item of clothing. The Tale of a T-Shirt(1) took its audience on a journey that began with students examining tags on their clothes (discovering that nearly all were made in China, Bangladesh, and Vietnam). Then, through a series of real and fictional vignettes the play chronicled the cotton seed’s international travels and transformations: first we were transported to the southern U.S., where cotton is planted and harvested; then to India where it’s spun into cloth; next to Bangladeshi factories where cotton shirts are sewn; then to British Columbia ports where finished T-shirts are shipped for distribution; and finally to Ontario where cotton T-shirts destined for retailers’ shelves arrive by train.

The actors brought a high level of energy and the vignettes were mostly playful and filled with considerable silliness – obviously designed by the theatre company to keep even squirmy eight-year-olds attentive. By the end of the show, the artistic director’s goal – “we want kids to know that their clothes don’t magically appear in the stores” – had certainly been achieved. But that’s just the beginning of what the students learned.

Children care deeply about justice

After the final curtain, the kids were especially eager to discuss the scene involving a fatal fire in an unsafe and poorly inspected garment factory in Bangladesh. During the play’s emotional climax, the fictional story paused, the theatre darkened, all joking ceased, and a painfully real photograph of the victims of the Rana Plaza building collapse and their families was projected onto the set. It literally set the stage for an animated and heartfelt conversation with the kids about our individual and collective responsibility to become informed and take action against social injustice. Nora, one of my son’s classmates, asked: “If we are paying $2 for a T-shirt, does it actually cover the cost of people dying and making sacrifices?” And then: “They make the T-shirts for us because we have money and they don’t.”

In the context of exploitation and human rights violations, we can’t be passive, and we can’t remain indifferent. Nora’s comment clearly demonstrates why there is no neutral position when it comes to social justice. We must support social, economic, and environmental justice. This is especially true if our actions as consumers or citizens have empowered those causing harm. At the theatre, the students’ deep engagement in real-world learning about social justice reflects a simple truth: Children want the world to be a fair place; they respond well when teachers help them learn why injustices occur. Back at school, my son’s teachers extended the inquiry by asking questions and planning activities supporting students to explore consumerism, poverty, racism, and environmental harms. Children are interested in learning – and they deserve to know – what they can do to make their world a better place.

Questioning the status quo and the curriculum

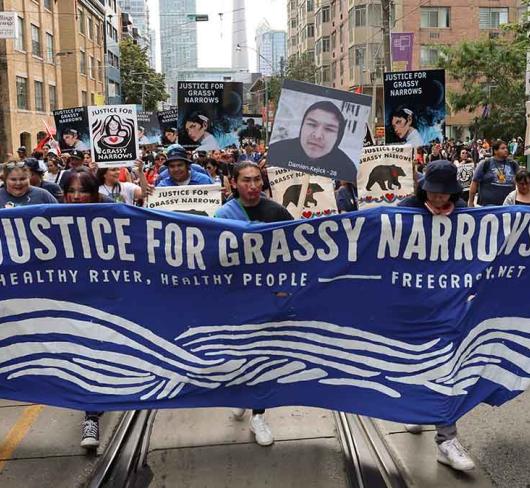

Given the rarity of field trips in schools, it’s fortunate that social justice education doesn’t depend on special events. It’s something we can do every day, every time we question and rethink the status quo. To do so, we need to avoid the trap of imagining that social injustice is something that mainly happens far from home. From the made-in-Canada travesties of residential schools and missing and murdered Aboriginal women, to child poverty and the growing gap between rich and poor, to racial profiling, human-driven climate change, and numerous additional issues, we have a very long to-do list of Canadian justice issues. Moreover, when we teach students about workers in the global south (including textile workers in Asia) who struggle for safer workplaces, better wages, and work with dignity, it’s important to show students commonalities as well as differences in the struggles low-income – especially non-unionized – Canadian workers face, as well as the interdependent solutions that labour activists and solidarity groups (such as the Maquila Solidarity Network) advocate.

Since students learn intentional and unintentional lessons from everything that surrounds them, it’s helpful to think broadly about how students actually experience “the curriculum.” Well beyond what the EQAO values, curriculum includes content (what we teach), and pedagogy (how we teach), but also access (whether students have real, meaningful access to learning materials), and climate (what the total learning environment is like and how it shapes student learning). Both the formal school curriculum (official Ministry policy) and the hidden curriculum (the unofficial, often-denied real-life lessons learned by students) fail to fully acknowledge and value the histories, current realities, and contributions of many groups: working people, women, Aboriginal peoples, people of colour, LGBTTQIA people, people with disabilities, and others. When groups are given second-class status in the curriculum broadly defined, there can be no doubt that it negatively affects the schooling experiences and educational outcomes of students from these communities. And, as a result, all students receive partial and inaccurate information about the world in which we live.

Inclusive curriculum

Social justice education strives for an inclusive curriculum. Emily Style describes inclusive curriculum as “a window and a mirror” that ought to balance two tasks: reflecting and revealing accurately a multicultural world and the students themselves. For Style, inclusive education needs to enable students to look through two types of frames: “window frames in order to see the realities of others and … mirrors in order to see [their] own reality reflected.”(2) In this way, inclusive education provides students with a balanced knowledge of themselves and the world.

I have found this metaphor useful for reminding me to balance similarities and differences in the lessons I plan for my students. It encourages educators to know our students – and our world! – very well. It reminds us to give more attention to the people and issues inside and outside our classrooms that tend to be ignored or excluded. For example, The Tale of a T-Shirt play gave students a windowwhen it drew their attention to groups and issues often ignored by the mass media (including the working conditions of Asian women and girls in sweatshops, and the social and environmental costs of globalization). It did so by holding up a mirror and asking students to examine a familiar object (a T-shirt) more closely and in light of new information.

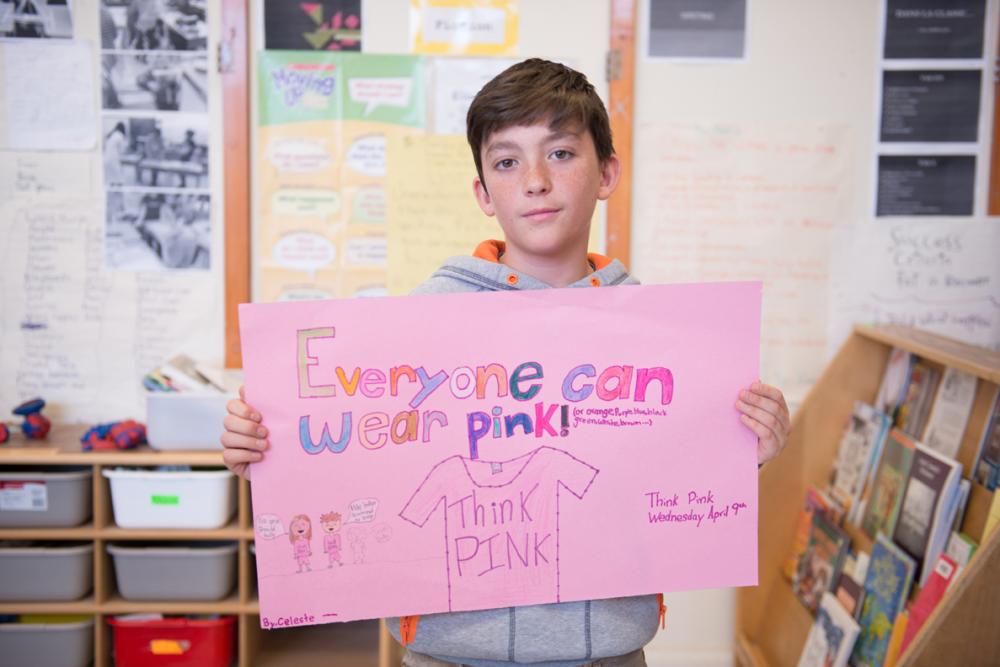

Curriculum as window, mirror…and door

I think Style’s metaphor would benefit from an additional third element, something to bridge the divide between self and other, the familiar and unfamiliar. It needs a symbol of movement and action. It needs a door. By adding a door to Style’s metaphor, I’m suggesting it’s necessary but not sufficient to help our students understand themselves and others from whom they differ. The door represents the capacity we all have to change and transform ourselves and our world. Children who care deeply about social justice need to learn how to actively challenge and change things – unfair practices, exploitative relationships, and unjust policies. Through the curriculum, teachers need to enable and encourage students to grow and become active participants in the making of a better world.

Social justice activism with young children: getting started

Teachers new to using activist social justice approaches in their teaching need additional support. There are many stellar social justice resources, in print and online, available through ETFO and school boards.(3) Working with like-minded colleagues from your school or your union, or taking additional courses, also allow you to share ideas and strategies and reduce the sense of isolation and hopelessness that so many teachers feel when confronting issues that sometimes seem overwhelming. Connecting with social justice community groups and supportive families also helps.

An excellent resource for primary and junior teachers is That’s Not Fair! A Teacher’s Guide to Activism with Young Children, by Ann Pelo and Fran Davidson.(4) Writing from the perspective of early childhood educators with decades of experience helping children learn about fairness, they offer reams of examples and many practical strategies for fostering dispositions for social justice activism in young children, planning doable projects, involving families in activist projects, finding supports, and knowing when to wrap up activist projects.

Their rationale for engaging children in activism is clear. Social justice activism:

- Nurtures learners’ self-esteem

- Develops empathy and appreciation for differences

- Facilitates critical thinking and problem solving

- Provides a mental model for learners at risk of bias and discrimination

- Provides a mental model of equity and justice for privileged, dominant-culture kids

- Contributes to community building across diversity.

When are children ready to learn social justice activism? According to Pelo and Davidson, learners need to be able to:

- Notice and (begin to) accept differences

- Be willing to collaborate, e.g., play together

- Pay attention to other people’s ideas, feelings, needs

- Express ideas about fairness and (in)justice

- Take responsibility for trying to solve problems and begin to offer ideas for action.

Finally, teachers wary of the term activism might be surprised by how normal social justice activism can be, and to what extent it already resembles what we think of when we think about good teaching. Pelo and Davidson identify four steps to social justice activist teaching:

- Listen to and observe your students and their communities (receptive role).

- Acknowledge feelings.

- Support critical thinking.

- Facilitate action (active role).

I would add two others:

- Continue learning, and providing and cultivating support for social justice work in your school, union, and wider communities.

- Remember that (social justice) education is a marathon, not a sprint, and that you can’t possibly do everything at once. At each step, focus attention on what you can do.

If we help our students understand the interconnections, similarities, and differences among different forms of social, economic, and environmental injustice and we enable them to move from understanding to action, we can and will build a more socially just world.

Terezia Zoric is a senior lecturer in Social Diversity in Schooling at OISE and chair of the University of Toronto Faculty Association (UTFA) Equity Committee. Terezia is also a co-founder of The Grove Community School, a former inner-city high school teacher, and the past head of the Toronto District School Board’s Equity Department.

……………………………………………………………………………..

1 The Tale of a T-Shirt is written and directed by Lisa Marie DiLiberto. For a review of the play, see Westhead, R. (2014, March 8), Toronto Star. Retrieved from thestar.com.

2 Style, E. (1998). Curriculum as window and mirror. In Cathy L. Nelson & Kim A. Wilson (Eds.), Seeding the Process of Multicultural Education, 149-56. St. Paul: Minnesota Inclusiveness Program.

3 See, for example, the CLC Working Voices website clcworkingvoices.ca/mobile ; ETFO’s Social Justice Begins with Me; and Zoric, T. et al. (2005). Challenging Class Bias. Toronto District School Board and Centre for the Study of Education and Work (CSEW) at OISE/UT.

4 Pelo, A., & Davidson, F. (2000). That’s Not Fair! A Teacher’s Guide to Activism with Young Children. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.